Letter from Chicago: Part II.

“Picasso and Chicago: the Fearless Pursuit of the Modern”

Art Institute of Chicago, Feb 20 – May 12, 2013

http://www.artic.edu/exhibition/picasso-and-chicago

By Cynthia Kukla

I returned to Chicago for the April 19th symposium on Picasso1 organized for the “Picasso and Chicago” exhibition and seeing the exhibition again strengthens my already deep appreciation of Pablo Picasso and reinforces his pivotal role in advancing modernism. In the exhibition, you view Picasso’s oeuvre chronologically, which aides in mapping his individual artistic progress and his crucial participation in the avant garde.2 The exhibition begins with Picasso’s early years, the Blue Period, with the Art Institute’s iconic 1903-04 oil painting Old Guitarist as its centerpiece.

Circle of Influence

The big surprise came with the excitement in seeing works of art in the museum that illuminated Picasso’s genius in borrowing and distilling from diverse works of art from various historic epochs. This special feature includes “nine special installations around the museum (that) explore sources of inspiration for Picasso and works by those he inspired.” We were on our own National Treasures hunt. In conjunction with the exhibition, the Art Institute wove Picasso’s own study of other art forms, such as 19th century African reliquary sculpture, and various artistic eras and artists he examined throughout the museum.

I had a chance to wander through the museum to site the specific scholarship that illuminated Picasso vis a vis the world of art. In the Spanish Galleries, the curators situate Old Guitarist, one of Picasso’s early and brilliant iconic paintings that owed an enormous debt to one of his classical Spanish predecessors, El Greco. Here is where it gets illuminating, seeing El Greco’s St. Francis Kneeling in Meditation and the wall text and small reproduction of Old Guitarist side by side. Picasso so avidly culled ideas and forms from various cultures and eras – all artists do some of this – but none better than Picasso, and we are in lived time, seeing one artist drink in the strategies of an artistic predecessor.

This is most evident in observing side by side how Picasso visually distilled the celebrated distortions of El Greco. Each of these anguished figures – St. Francis and the blind musician – are isolated in melancholy and meditation, the saint praying, hand on prayer book, the blind guitarist’s hand playing his guitar. El Greco’s signature elongated limbs and facial features are what Picasso boldly borrows. The blind guitarist could be El Greco’s anguished Francis: strikingly similar body exaggeration, paint modeling, interpretation of garb and isolation of figure. Each painting has a patch of blue sky behind and each lonely figure conveys “I am so alone here yet the world is out there.”

In the Spanish Galleries, next to the Art Institute’s El Greco straightforward portrait of St. James the Lesser, is an early work by Picasso, reproduced in the wall text, his 1899 Face in the Style of El Greco. Here is direct evidence of Picasso’s absorption of his Spanish predecessor. Picasso is said to have told his dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler that he admired El Greco’s portraits and his depiction of heads. We may forget that artists once set up easels and canvas in museums and studied and copied masters as part of their schooling or artistic apprenticeship, a practice nearly lost now. Picasso had numerous opportunities to view El Greco’s paintings in museums and in one spectacular special case, in a dealer’s salon.

As with St. Francis and the blind guitarist, Picasso again borrows, now horse and man iconography. The Art Institute’s El Greco’s St. Martin and the Beggar’s iconography and composition were borrowed by Picasso for his Boy Leading a Horse from Picasso’s Rose Period. The religious narrative is dropped, but a meditative feeling remains. Just as St. Martin is in a spare landscape, so is the boy leading a horse, so all focus is on figure and horse. Picasso examined lives of marginalized groups, such as saltimbanques, itinerant circus performers, to which this boy and horse belong. Is Picasso saying, though they are not saints, they are marginalized by their corrupt societies, like saints were? Picasso, steeped in Spanish Catholicism, certainly imbued his contemporary secular work with pathos, if not religiosity. The Rose Period galleries of the exhibition also vividly call attention to Picasso’s careful study of the Louvre’s collection of classical antiquities, his absorption of Ingres’ classicism and of Puvis de Chavannes’ themes and pastel palette. There is also obvious absorption of the formal considerations of ancient Iberian sculpture in the Louvre’s collection and in the Trocadero Ethnographic Museum.

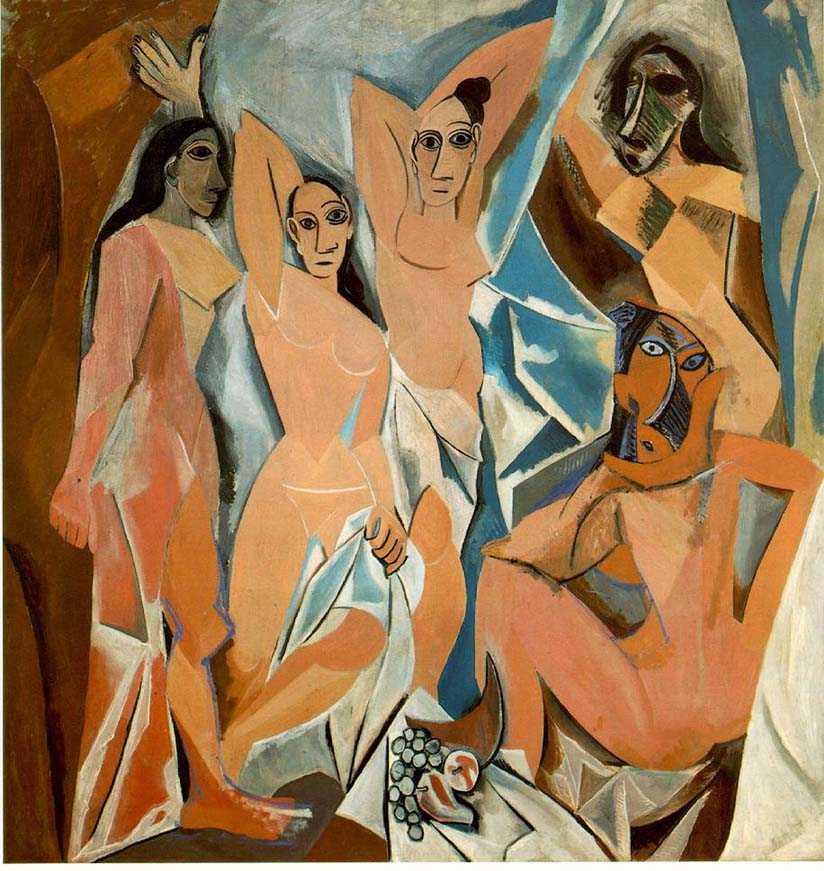

In the Art Institute’s Spanish galleries, the most stunning connection between El Greco and Picasso occurs in examining the Art Institute’s enormous El Greco Assumption of the Virgin and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Each painting is groundbreaking in its time and for all time. With the wall text analysis and small reproduction of Demoiselles next to El Greco’s masterpiece, I could track Picasso’s distillation of El Greco’s interpretive and stylistic genius. It would be a stunning exhibition to have the actual, large Demoiselles next to the enormous Assumption. The borrowing by Picasso would be even more shocking and vivid.

Some background is in order. Picasso must have seen the Assumption in the Paris gallery of Paul Durand-Rouel sometime between 1904-05. It had been in Henry Havemeyer’s private collection and with his passing was being sold. (In 1906 it was purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago.) Robert Rosenblum sees connections whereby Picasso combined the Spanish visionary Catholicism of El Greco in the context of a brothel – a disturbing distillation of the Catholic virgin/whore conflict. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted in 1907, was shocking when first viewed, even if any connections to El Greco’s Assumption of the Virgin were many decades away from being made.3

On my own National Treasures hunt, I was looking for significant clues. I know the Assumption almost by heart, seeing it every day on my way through the museum to the School of the Art Institute, when the School used to be behind the museum. What a gift, a young artist looking at art from around the world every day after walking from the subway, through the museum and on to classes. I found an amazing correspondence between El Greco’s flattened forms, that is, bodies and fabric not highly shaded and modeled, especially the Virgin Mary’s sarcophagus which was absolutely flatly painted, and with Picasso’s seminal 1907 masterpiece. Think of Demoiselles, all flat shapes with no modeling. The Assumption is a symphony of triangles, sharp diagonals and sweeping fabrics that are taut, pointy. This painting is over three hundred years in advance of Cubism. No small wonder Picasso fixated on El Greco. Demoiselles is also composed of triangles, sharp diagonals and sweeping fabric that is taut, pointy. The drapery behind the prostitutes could be directly lifted from the shoulders or hips of Mary’s male protectors who witness her Assumption into heaven. Thinking of the numerous (about 500) preparatory drawings for Demoiselles, is Picasso saying, “A brothel is heaven for a young man”? I fear so.

I also focused on the beautiful sliver of moon, a beautiful shimmering crescent that Mary rises on in her ascent to heaven. It is a beautiful part of classical Mary iconography (tying her unintentially by the male Catholic hierarchy, to her pagan source, Diana the virgin goddess or Hera the mother goddess, among many goddess sources.) Ancient Greek statues of Hera have the same cloak and veil as Mary and we might forget that Mary worship persisted by the agrarian people when very early Christianity attempted to marginalize Mary and suppress prior pagan regard of the Great Mother. The moon is associated with the divine feminine and in tribal societies the feminine cycles were linked to the phases of the moon. It is no wonder that El Greco retained this potent symbol, which would have been painted and carved in countless cathedrals, tombs and archaic artifacts throughout Spain. The pearly blue-gray clouds behind the Virgin silhouettes the crescent moon and gives it delicate prominence. Thus, its symbolic potency cannot be overlooked by either a reverent El Greco or an irreverent Picasso when he specifically made a groundbreaking Modernist work with the subject of prostitutes: reverence by one and revulsion by the other.

Look at Demoiselles. Even if unconsciously, Picasso places a bowl of fruit before us, near the prostitutes on the right with a melon that is a sharp, pointy crescent. The fruit is also obvious Edenic reference, woman as temptress. The squatting prostitute on the far right, the one with the most grotesque African-inspired head, is squatting on a crescent-like stool, her back to us and though she is sitting with legs splayed, her sexual promise is concealed from us. The ripe crescent melon placed in front of us is the sexual triangle, a feature of archaic art, to represent the vagina that the brothel patron seeks. Picasso gives us the sexualized fruit but no one sees nor gets what he really wants until he pays. The sacred and profane is a universal dichotomy, and has special resonance in Catholocism.4 Being raised Catholic myself, I know of what I speak, though I prefer seeing El Greco’s Assumption in its pure and uplifting form. It retains its power and purity, in a separate sphere from this particular analysis.

After viewing the special installation in the Spanish galleries, I viewed the artwork in the African Galleries; African sculpture had so influenced Picasso. It was revelatory to see a featured photograph of Picasso in his Bateau-Lavoir studio with the African sculpture he had purchased surrounding him, providing evidence that Picasso had the African art on hand to draw upon. Literally.

Rappel d Lordre

I found another place where Picasso’s cannibalistic artistic practices were evident. Though not highlighted specifically as part of the nine special installations, I carefully examined two Pierre-Puvis de Chavannes paintings. In Part I of my analysis in the March issue of Aeqai, I referred to the museum’s referencing of Puvis as an influence on Picasso. Today, in looking more closely at two paintings on the second floor of the museum, I came away, again, with the same clear feeling of Picasso lifting heavy pieces, this time of the 19th century Frenchman Puvis de Chavannes, and of Picasso painting them right into his monumental Mother and Child of his Rose Period, one of the major works featured in the exhibition. I say this because in examining de Chavannes’ Fisherman’s Family, there is such a strong affinity between it iconographically and Picasso’s Mother and Child. The modeling of Picasso’s Mother and Child is so like the modeling of de Chavannes’ mother and child; the same classical Grecian drapery and buffy pink and powdery blues and gray palette of colors, the same sculptural quality in the painting of the figures, like painting while looking at an ancient Greek sculpture. The flesh is not a healthy, living, yellow-peach beige heightened with touches of Venetian red and umber, like Caravaggio or Rubens, but gray-beige and pale pink, as if Puvis, then Picasso, were sitting before a marble statue of Hera in a museum in Athens or Istanbul. De Chavannes’ baby is chubby with animated arms and hands, just as Picasso represented the child in his family portrait. Picasso’s Mother and Child had the father reaching over to the mother in its original, confirmed via x-rays of the painting, just as de Chavannes’ father hovers protectively over his family. And finally, both paintings have the setting by the sea.

The second de Chavannes’ painting that gives rise to my observation of Picasso’s heavy lifting is The Sacred Grove, Beloved of Arts and the Muses. All the reclining goddesses/muses look like Greek statues, rooted to their marble bases. De Chavannes’ draws his goddesses and muses rooted to the Arcadian earth. They sit and inspire, statue-like. Picasso situated his Mother monumentally, rooted in the earth, the same Mother Goddess seen throughout Europe from prior millennia. Said simply, Picasso took de Chavannes’ delicate Arcadian goddesses and made them significantly larger, as wont of his times. A comment should be made here on Picasso’s view of women, monumentalized when in motherhood, but at other times treated pictorially with other less honorable intentions, seen in other parts of the exhibition, such as in the small Surrealist section of this exhibition.

None of these observations of Picasso’s attention to prior art works and of his aggressive borrowing is to discredit Picasso. That would be ridiculous. Picasso’s output and contribution is protean. I wish to underscore Picasso’s genius, discussed at length by astute scholars of Picasso, but also to underscore Picasso’s borrowing, stealing, distilling, revisiting and appropriating both popular and unpopular artists and styles and giving them new life with his remarkable mind and hand. From a perspective of Postmodernism and feminist interventions, one could claim Picasso pillaged or raped art history itself. When we look at art, the art is passive, as if feminine. The art actions by Picasso are consistent with his treatment of women.5

Also take in mind that while Picasso was still working on Cubism, he simultaneously embraced his classical work, what poet Jean Cocteau called “rappel d lordre” (call to order.) Picasso’s Mother and Child of 1921 is a stunning example of his classical paintings. More sculpture than painting in visual effect, this may also be attributed to Picasso’s travel to Italy and the influence of classical antiquity on him. The scale of his mother and child is utterly monumental and the modeling is as if he was making a painting while looking at a sculpture of these figures. The mother’s profile seems to owe directly to classical portraiture idioms, the straight line from top of forehead to nose, the slope of eyebrow and shape of eye and eyelid all echo the classical Greek portrait model. But my overarching impression is of Picasso’s searing intellect, selecting among a diversity of artists and styles and sifting through the innumerable possibilities and with his thousands of drawing, prints, paintings, assemblages and such like, making new forms that advanced twentieth century art.

Certainly, the ancient Mediterranean continues to speak to artists, not only Picasso, but Jim Dine, whose Glyptothek drawings6 done in museums in Germany and Denmark are a forceful contemporary interpretation of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures. Leon Golub began his Gigantomachies series after his art fellowships in Italy. In the 1960’s the enormous battling, wrestling figures were based on classical models, including the Hellenistic Altar of Pergamum. Transformed from the classical with Golub’s brutish, contemporary methods – acrylic paints abraded by meat cleavers to create aggressive textures, were so unlike the soft blending deployed by Picasso in his classical figures. Yet, without Picasso’s lead, at the time of aggressive Modernist abstract ploys, Golub may not have taken the steps he took. These artists, walking among ancient ruins, no doubt shocked and mesmerized by the scale of ancient figural sculptures, returned to their home studios changed. Picasso led the way.

Picasso was among the first artists in the 20th century to look back that far, to ancient Greece and Rome, while the Futurist Manifesto, Orphism and various non-objective strategies were all at the forefront of the modern painting machine. Picasso of course was not the first to be affected by archaic art. The Grand Tour has been a feature of artistic luminaries since J.M. W. Turner, and of artists of times before him. Yet, to re-embrace the classical, with Mother and Child in the pink, buff and gray palette of his Rose Period, so reminiscent of Puvis de Chavannes, was a daring strategy. Modernism was well underway and non-objective abstraction was in place since Malevich’s 1915 Black Square. It is clear that Picasso’s humanism and love of the human figure governed his studio decision-making. The human figure is Picasso’s lodestar. Picasso’s embrace of abstraction was never all or nothing as it had been for Mondrian. The figure as part of living and experiencing the world was always Picasso’s armature.

1The symposium had all good topics, especially Michael FitzGerald’s lecture “The Armory Show and After.” Arts Club of Chicago director Janine Mileaf spoke on “Hosting Picasso: the Arts Club of Chicago in 1923” and Diana Widmaier Picasso spoke on “Pablo Picasso and Monumental Sculpture (1963-1967), a Case Study.” For my research, I found greater impact in the nine related exhibitions prepared by the curators.

2The leading authority on Picasso, among many, is British scholar John Richardson. His A Life of Picasso biography, (originally planned to be published in one single volume), was published in 1991, describing 25 years from Picasso’s birth to 1906. It won the British Whitbread Award. The second volume was published in 1996, covering 10 years from 1907–1916, covering the birth of Cubism, followed by the third volume in 2007, devoted to the period up to 1932, when Picasso turned 50. Richardson is currently working on the final volume with Michael Cary and Gijs van Hensbergen. Knopf has scheduled to publish it in 2014.

3A clear discussion of Robert Rosenblum’s analysis of Demoiselles is found in “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Revisite,” Artnews, LXXII. No 4, April 1973.

4See Eleanor Heartly, Postmodern Heretics: Catholic Imagination in Contemporary Art, Midmarch Art Press, 2004.

5This observation on the perspective of Postmodernism and feminist interventions viv a vis Picasso occurred in discussion with editor Daniel Brown and our mutual perspective on the matter.

6Jim Dine, Drawings from the Glyptothek, Cincinnati Art Museum, October 23, 1993 to January 2, 1994. Originating at the Madison Art Center, Wisconsin, it also traveled to the Contemporary Art Center, Honolulu, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and Center for Fine Arts, Miami.

Cynthia Kukla is an artist and art professor living in Illinois.

- El Greco’s “St. Francis Kneeling in Meditation”

- Old Guitarist

- Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted in 1907

- Jim Dine, Glypthoteck

- leon-golub

- Picasso, Mother and Child