United We Stand: A review of Artists as Activists curated by Saad Ghosn.

By Cate Yellig

It was a rainy April afternoon in 2006 when for the first time, I was challenged with the question does activist art really effect change. Sitting in a Contemporary Art and Theory class, a battle of wits ensued as one argument was made in favor or against. To me the question seemed easy; yes, artists or anyone for that matter could be a catalyst for change. I argued, if they were steadfast in their beliefs, had a strong message, and spoke it loud enough, how could they not bring about change? In the end, it was really a matter of whether or not anyone was listening.

The time is ripe for listening and Artists as Activists is an exceptional opportunity currently on view at the NKU Galleries. Curated by Saad Ghosn, a doctor, prolific writer and curator of thought provoking exhibitions like SOS Art, Artists as Activists is the culmination of a two year endeavor fueled by passion and desire for peace and justice.

Between September 2009 and August 2011, Ghosn penned a bi-monthly column for Street Vibes. Each column subtitled, ‘Art for Life’ provided a platform for the artists’ voice, to address their concerns not for the sake of art, but for their own benefit, for their lives, and for the greater good.

Following a similar format, each article featured a local artist(s), one artwork, a brief explanation provided by Ghosn, and discussion by the artist about their values, beliefs, concerns and inspiration for their creativity. In the end, Street Vibes published forty-eight articles and featured forty-four visual artists, four poets and writers, and one singer/songwriter.

To further explain the immense undertaking, I interviewed curator Ghosn to find out more about his inclinations and to delve deeper into the question about activist art.

CY: Why do you curate shows like Artists as Activists or SOS Art?

SG: Two things really. One, I believe in art as a voice for artists which reflects their beliefs, who they are, and that art is for the artists’ sake and it is created to please the maker. It is an aesthetic exercise where all becomes a message and not just a commodity. I also do not feel that activist art is only political; it reflects ‘you,’ your message, and your ideas.

Secondly, we need to create a community or a platform of expression to strengthen artists’ voices. By doing this we create more resonance with our voices, they become stronger, more connected, and this breaks down isolation.

CY: Do you encourage or embrace a ‘populist’ approach for your shows? If so, do you believe this creates a stronger or more cohesive platform for your concept?

SG: My show SOS Art was by definition and principle, non-juried, open to anyone and any level of expression. It was not a show about exhibiting quality, rather looking at ‘what do you want to say?’ And the artists strengthen each other. I would say then, I am for a populist approach as arts is a vehicle for peace and justice.

The SOS Art show was an annual exhibit and to keep it going through out the year, Artists as Activists was a result of this inquiry. I worked with Greg Flanery to keep it going, the idea was to feature the work of one artist every two weeks in Street vibes magazine. Over 2 years, 48 artists were published creating a platform and community.

To document the community, Michael Wilson was the photographer I reached out to to take portraits of the contributing artists. Their interviews and portraits will be in the catalog published for the show, which was created as a celebration of our community.

CY: How does your own background influence your curatorial vision?

SG: Peace and justice came from growing up with the message of being good, kind, and passionate. This part of the equation is part of me.

There was a time where I was curating shows about spirituality and more interested in aesthetic inquiries. At the time I was teaching at medical school and began curating shows at the medical library about diversity and exposing students to spirituality. Students would stop to look and react. I had a work by Jeff Casto which had words like racism and empowerment on it, and some students got offended. In a library you sit and meditate and art grows on you.

But after the riots of 2001, 9/11 and the implementation of the Patriot act, I felt I was living against myself. I do not want to preach to the choir or convert people to believe like me. But I do encourage those to assert who you are, to state your vision with the hope it that it make you stronger. I want to empower artists and people, and to entice viewers to discover and to be touched.

CY: Do you think people are listening to ideas like this in America?

SG: Until about ten years ago museums and galleries focused on non-threatening art. It was focused often on modern aesthetics or conceptual art and became elitist with how it was discussed. This influence was deliberate and it imposed choices and ideologies on art and our society. The idea of, let’s use the more ‘unthreatening’ forms of art. It established an environment where there were no venues for artists who created work about their beliefs.

The need for artists to “say” something, you now see this more often. It is easier to have shows about beliefs and that type of art involvement builds community and acceptance of peace and justice.

I have been approached by artists outside of the region to participate in Artists as Activists. I always use local artists, so for those who are in San Francisco or other cities I encourage them to emulate ideas like this in their own cities.

Despite the diverse array of styles and mediums, there are important themes pulsating beneath the surface exploring the effects of crime, poverty, war, destruction of the environment and the consumption of resources, materials, and people. To understand these themes are not only relevant but incredibly up to date, one needs only to turn the television on for a mere second and watch the local news. Environmental concerns, women’s rights, violence, and concerns of the working class provide content for every news ticker and sound bite.

In the show we see artists addressing environmental issues, such as Roscoe Wilson’s 87 Days, black and white linocuts referring to the devastating impact of BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Here eighty-seven individual works on paper represent the number of days it took to stop the spill. Wilson’s work explores the dilemma of consumerism and waste in contemporary society.

Mixed media painter and sculptor Gena Grunenberg, explores violence against women on domestic and societal levels and believes women of the world are not supported and in danger of losing rights to their own bodies. In Captivity is a three dimensional sculpture of a woman chained to a stake in the ground protecting a small nest of crackled eggs. Her hands handcuffed together by the same material as her ring and necklace. Towering above her nest, her contorted little body is painted in a matte blue, a color reflecting her grief filled eyes. In her hand she holds one of her eggs and looks up sorrowfully to the sky, as if she knows not what to do with it anymore. Is she captive to her own beliefs or to those imposed on her by society?

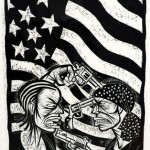

We often hear about gang violence in Cincinnati, driven by drugs and crime, poverty, and little opportunity available for urban youth. After witnessing a gang fight, late artist Tom Shaw explored the nature of street culture, prostitution, and gangs with a body of work called The Malcolm X Paradox. The name came from the unsettling fact that the purveyors of the fight were wearing t-shirts bearing the name Malcolm X.

Shaw was an artist from Cincinnati who embraced the stylistic influence of German Expressionism, the haunting black and white woodcut. The Malcolm X Paradox: Gang Killing depicts two young males, angst ridden and standing face to face with guns drawn. Behind them the stars and stripes of the American flag dominates the upper portion of the work on paper, overpowering the composition as if the weight of its existence oppresses the men below. Gnashing their teeth, the lines of their angry faces bear witness to the weight of their existence.

When contemplating the theme artists as activists, and how activism suggests the need for change, is it pertinent to question whether this is a personal need or a communities’ need? Is this journey one that everyone, the common (wo)man can empathize with and believe in?

An outstanding example of artwork exploring the plight of the working class would be The Patriot by Kelly & Kyle Phelps. The brothers grew up in a blue collar factory environment in Indiana, the everyday people in their lives became working class heroes and found their way into their artwork.

A hand crafted assemblage of clay and resin recounts the story of a homeless veteran, an unfortunate scene that has become all too common. A man, whose face is weathered from experience, looks downward as he holds a small, tattered American flag. He pushes a cart filled with trash bags, a small picture of Jesus is partially obscured by his belongings. The three dimensional sculpture is framed within a larger American flag. This is not the bright and clean version we are used to seeing flying high at ball games and schools. This flag is dirty and gray, it has seen better days. Their hand-crafted work is effective and provides a visual narrative about the blue collar experience while producing an authentic and tactile sense of place and time.

Prior to discussing the curatorial vision of the show with Ghosn, and perhaps admittedly influenced by the discussion from my educational past, I could not help but wonder whether these artists really feel that by calling attention to an issue they can effect change? If change is not the end goal, then does calling attention to an issue really empower or does it solely point out the insufficiencies of our capabilities?

Incredibly diverse works of art can be seen throughout the exhibition, painting, sculpture, poetry, installation, assemblage, even sound round out the rallying cry of Artists as Activists. With fifty artists, portrait photographs, and biographic statement the walls are full of details fighting for the viewer’s attention. This is an exhibition that requires time and genuine interest as the beauty of its message is found in the minutiae.

–Cate Yellig