ART FOR A BETTER WORLD

by Saad Ghosn

I. Images For A Better World: Scott DONALDSON, Visual Artist

Scott Donaldson graduated in 1982 with an MFA degree in Theater Arts from the University of Minnesota.

Until 1990 he worked professionally as a set designer, also as a scene painter for 5 years with the Kalamazoo Civic Players. In 1990 he became an exhibit designer for the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, and has since worked in the same capacity in such places as the Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, OH, the National Underground Railroad and Freedom Center, Cincinnati, OH, and the Tech Museum of Innovation, San Jose, CA. All along, he freelanced as well.

In 2003 Donaldson began to pursue a career as a fine art artist, continuing at the same time as a freelance independent exhibits designer. In 2005 he received an Individual Artist Grant from the city of Cincinnati to produce 11 drawings and paintings retelling stories of the Underground Railroad set in modern times.

Donaldson’s art has been exhibited widely, including in the collective show A is For Ahimsa, in several SOS Art group shows and in numerous solo shows including ‘Tune In Turn On and Hook Up’ at ArtWorks Gallery and ‘Face to Face’ at The Carnegie, in Covington, KY.

From 2007 to the present Donaldson created 15 murals around Cincinnati, leading teams of apprentices, professional artists and volunteers. Among his most notable murals are some he created for ArtWorks, ‘Campy Washington,’ a humorous play on words, ‘Cincinnati’s Table,’ on the wall of Jean Robert’s LeTable restaurant and ‘Garden Party at the Taft,’ in Bellevue, KY. In addition he designed and completed murals for businesses such as Stewart Tire and Auto Services, a subsidiary of Goodyear, and GE’s Aviation Division, in Evendale, OH.

When asked about the value of Community Murals, Donaldson answers that it is ‘All about Pride.’ He thinks the muralist’s job is to engender a sense of pride in the community for which the mural is painted, be it a neighborhood association, a company, or a specific group. Over the years he has attended many mural design meetings and has found recurring themes the committees in general wanted to convey through the mural, namely ascendance, pride, coming together, moving forward; the mural serves as a local icon in its environment.

As a designer Donaldson feels his role is vital in moving these meetings from the spiritual/intellectual to the concrete visuals part of the design. To achieve this he usually resorts to two invaluable rhetorical tropes, metaphor – something different standing for something else – and his favorite, Synecdoche (from the Greek, meaning “simultaneous understanding”) – a figure of speech in which a term for a part of something refers to the whole of something, or vice versa, such as for instance “wheels” for a complete vehicle or “handlebars” for a motorcycle.

Armed with such analogs, Donaldson would start hunting for images as a base for his design, triggering talks and brainstorming among the committee members to help visually focus and narrow the larger idea. Using this approach has helped him all along reach a strong and well-focused mural design, avoiding clutter or creating just a pretty background. “When the mural works, the pride of the community shows,” says Donaldson. “The overall feeling becomes: ‘yeah I live here and we have this cool thing to show off.’”

The following five murals that Donaldson created illustrate his previously stated approach.

- Camp(y) Washington, mural painting

Preparing for what resulted in “Camp(y) Washington”, the neighborhood association of Camp Washington wanted from the start an iconic and eye catching mural. A play on the word “camp” led to the image of George Washington in a dress to which was added the image of the courageous cow who jumped the fence of the neighborhood’s slaughterhouse to escape being turned into sausages; it ended up being rescued and adopted by the famous Peter Max to live peacefully and happily on his farm.

- A Great Day in College Hill, mural painting

Preparing for a mural in College Hill, it was discovered that the neighborhood had the oldest recordings of the weather in the country. Taking advantage of this piece of history, Donaldson decided to include in his painting many weather vanes, an indirect reference to the community, its farmers’ market, its long time interest in gardening, and therefore its history. The community decided to place a key to the vanes next to the mural which was titled “A Great Day in College Hill.”

- Cincinnati’s Table, mural painting

“Cincinnati’s Table,” a mural Donaldson did for the wall of the restaurant owned by the renowned French Chef Jean Robert, includes images of French food and of the animals that go into it. Donaldson chose the rooster as the focal point of his mural due to the rooster’s usual fierce character.

- Riverside Rides, mural painting

In “Riverside Rides” Donaldson referenced transportation as it related to the neighborhood and its history. The mural shows a target that BMX bikers use as a goal to reach. Close to the mural is a parking lot that is used for classic rally cars.

- Garden Party at the Taft, mural painting

In the mural “Garden Party at the Taft” Donaldson used as subjects some of the Taft’s iconic pieces of art, their images seeming to come out of the painting, as if inviting the audience to join in the fun.

Donaldson’s next two art pieces illustrate both his technical mastery and his often whimsical approach, characteristics that proved important in his selection for the design and creation of murals.

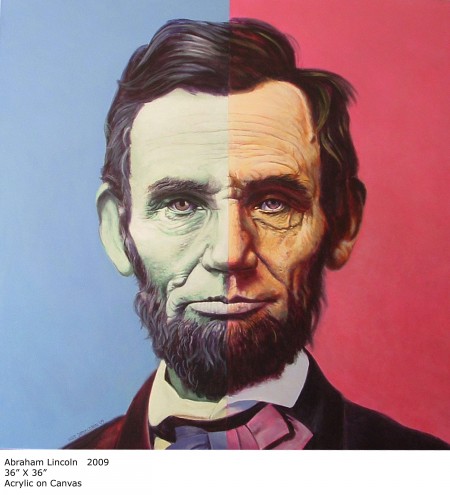

- Abraham Lincoln, acrylic on canvas

The portrait of “Abraham Lincoln” shows the precision inDonaldson’s painting skills, as well as his strong sense of design when applying and combining colors.

- Dropper’s Dream, acrylic on canvas

“Dropper’s Dream,” a painting he did of a squirrel pet belonging to one of his friends, shows the squirrel sleeping, dreaming of surrounding balloons containing nuts and acorns. It points to Donaldson’s sense of humor and to his playful and imaginative nature.

II. Words For A Better World: Richard HAGUE, Literary Artist

Richard Hague was born and raised in the river town of Steubenville, in the Appalachian eastern part of Ohio, famous for its high school football teams, and now equally infamous for the rape case and conviction and imprisonment of two of its star football players; the story made national news. Hague’s growing up took place in two distinct environments: the urban, industrialized Steel Valley, and the rural, poverty-ridden counties south of Jefferson County, just north of the town of Marietta. The whole region is currently a center of gas exploration and speculation, with tens of thousands of acres of mineral rights being leased every year. Already scarred by strip mining and other polluting and extractive industries, the region will now be enduring, in addition, the ravages to landscape and human infrastructure that come with horizontal hyraulic fracking.

Hague is author of fifteen collections of writing, including: Ripening (The Ohio State University Press, l984), for which he was named 1985 Co-Poet of the Year in Ohio; Alive in Hard Country (Bottom Dog Press, 2003), named Poetry Book of the Year in 2004 by the Appalachian Writers Assoociation; Milltown Natural: Essays & Stories From A Life (Bottom Dog Press, l997), then a National Book Award nominee; and During the Recent Extinctions New & Selected Poems l984-2012, which won the prestigious Weatherford Award in Poetry in 2012.

For forty-five years, Hague taught literature and creative writing, humanities and assorted other courses at Purcell Marian High School in Cincinnati. The Writing Program he organized and administered there won First Place in The United States for Excellence in English from The English Speaking Union. Over the years, his students have won hundreds of awards, prizes, and scholarships for their creative writing. That career came to an end when he refused to sign a new contract containing anti-gay and anti-workers’ rights issues in May of 2014. He continues to give workshops and lectures, and occasionally helps lead creative writing workshops at Thomas More College. Hague is married to Pamela Korte, Assistant Professor of Ceramics at Mt. St. Joseph University. They have two grown sons, Patrick and Brendan, both residents of Cincinnati.

1. Hague has occasionally been working on this sequence of poems for several years now under the working title “A History of the Former World.” At this time of climate change and economic turbulence, it doesn’t seem to him that business as usual is a likely forecast. These poems protest what he sees as unsustainable or outright destructive policies and habits of behavior and of mind. Even though big books have been written on planetary issues, as a poet, trying to live small in a threatened world, Hague feels obligated to speak briefly, more locally, and perhaps more sharply.

from A History Of The Former World:

“Also in America”

Also in America, Stupid often ran things:

the mayor of an air-blasting,

water-fouling steel town

who knew nothing of

falcons or vanishing shad;

the school administrator,

always indoors,

always hunched before her tiny computer

in her tiny room,

suppliant before the idol,

blinded by terabytes and spread sheets,

while outdoors, under

the freest, sun-charged sky,

a vast school garden went unplanted.

In America, Stupid was often in charge:

the bean-counter

who watched test scores

more closely than teachers

and students;

the technophile, looking to wire his school,

who declared a room full of books

“clutter;”

the ed-tech-biz operative

who sold her soul

to the maintenance of machines

and the eventual extinction

of teachers.

In America, Stupid often triumphed:

renewed bombing

to secure peace;

the bushhogged “eyesore”

weed-rich lot

reduced to naked soil

and finely-chopped trash

(“we had to destroy the field

in order to mow it”);

the neighborhood grocery,

fresh produce, fresh meat,

the only island in the food desert

of the ‘hood,

credit to all,

free delivery to the aged,

family-run for fifty

years —closed by the State for a minor

food-stamp violation.

In America, Stupid often seduced:

showed its comely frame

to investors and traders of

mortgages;

offered moist incentives

for cutbacks in teachers

to meet the budget

while football

thrived at a loss;

handed out cakes and candy

to fast-fooded

diabetic children,

sold even more gizmos and couch-

based devices to keep

them unexercised and fat;

demolished farmland

for the installation of malls;

poisoned the night with

parking lot lamps;

shilled capital gains

and farmland losses—Yes!—

as clear progress toward

bigness and profit.

2. It doesn’t appear that the planet has a single spokesperson with the amount of authority, gravitas, and/or notoriety necessary to make its woundings and its ruins common knowledge. Indeed, “common knowledge” begins to look more and more like deliberate ignorance, especially on environmental and climate issues which loom like a storm of global extent. As a poet who often finds nature the source of his imagery and attitudes, Hague has a vested interest in alerting others to the reality of annihilation caused, in large, by our destruction and exploitation, often for profit, of Creation.

from A History Of The Former World:

“Not All Sides Are Represented Here”

“Not all sides are

represented here,”

the quibblers, rabid capitalists, and

conscienceless would say,

“computers have more

up sides than down. War may be just.

Nuclear is necessary.

Coal can be clean.

Points of view,” they would say,

will differ.”

But the world,

the planet, did not reason,

did not equivocate,

but simply acted according

to its laws, most of which

they did not know—

for example, why so many

kinds of beetles? How much

smoke is too much?

Will oceans survive?

World was acted upon,

oftener and oftener,

by forces it could not

digest or comprehend:

5,000 new chemicals

every year, vast spills

of oil, billions of

fracking gallons poisoned and

lost to the water

cycle.

But there is not

an infinity of sides:

A box stops.

A diamond ends.

Cards flip once.

A world,

as we have seen,

can die.

3. For quite a while it has seemed that the Mid-east wars would be continuous; indeed, administrators called one of them “The Long War,” as if trying to convince us that permanent war was the ‘new normal.’ Such nonsense is still being fed to us. The poem Interrogation “During The Old War” harks back to WW II, just after which Hague was born. Raised in a postwar boom, simultaneous with the Cold War, he had a lot to learn, and then, a lot to unlearn.

Interrogation During The Old War

How large childhood remains

even after years of recollection,

vivid acreage without borders,

inhabited by infancy and boyhood.

Most everything was new then,

glint of skink or fence swift,

smell of copperheads,

the way a fire in the backyard oil drum

where we burned the trash

hissed and stank as it died.

Was there no moment or question

that did not pry open a strange door?

No, everything was new

as any of Emerson’s gods of the days,

and every one wore new clothes, ribands of

stratocumulus, that new word that made the world

and my eyes new,

or stood beaded with tiger beetles quick as light

on the sand of the riverbank,

and the river itself, that recent

eater of a girl I loved, that giver

of catfish and shad,

that tormentor of snags and broken herons.

Were there no repetitions beyond the wren’s scales

sung in the yard every morning?

Always—

and a cascade of vocabulary:

the day I learned sperm,

the day I learned alibi,

the days I chanted my altar boy Latin

and first pounded my chest

at the Confiteor:

Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

Was there no end to verbiage, to saying, cursing, yelling

praying, blabbing in the blab-school years

of times-tables and the names of presidents?

Never: everywhere amid a rain of nouns,

stabbed and urged and soothed by avalanches of verbs,

tilted off-center by the adverb or strange adjective,

I reeled alive in words.

Only much later

did I learn of and mourn

the slaughters forwarded by politicians,

the confoundings that would not answer reason’s call,

the outrages unjustified and unimpugned,

the skull-like grinning silences of war,

the dear, many, tongue-tied dead.

4. For Hague, the domestic and the artistic are really inseparable. His poem “Balancing” is a kind of attempt at magic: as if by saying balance is possible, it may well become so. Along the way, the poem also gave Hague the opportunity to say nice things about some nice situations and some nice people in his life.

Balancing

On the one hand

fatherhood, adventures in teaching and writing

filled with talking, language

and the working silences in between;

the sweet drudgery and happy detail of my gardens;

the laughter and wild talk of my children;

the continuing surprise of my wife,

opening like an endless bloom of contention and delight;

even the cats with their

raucous midnight excitations and couplings;

even the littered dark

in the corner of the basement among a hundred

half-done projects, where spiders live

with their roach hulls and husks of expatriate beetles,

where wrenches lie unturned and

nails unhammered

near the fire-breathing hiss of the furnace.

On the other hand

how attractive the silence of the bachelors

of fields, silent Trilliums in the woods, and Lady Slippers,

desert fathers in their hot dark cells;

all monks, hermits, bums,

even the blessed down-to-the-bone

homeless, the out of work;

the ecstatic, high and unconscious,

the perfect sleepers

I would sneak about at night to join:

intense velvet solitudes of moles;

dormers of hornets in the winter ground

over which low snows softly sweep.

Rest. The losing of names. Hours vacant.

Centuries of sweet nothings.

5. “Landscapes, Near The End” is part of a series of poems Hague wrote for the Now & Then Magazine’s “Industry in Appalachia” issue. He dedicated it to the young West Virginian woman who was raped by the boys from Steubenville. It is meant to remind us that what Wendell Berry has said: “We cannot treat one another any differently than we treat the land,” is indeed true.

Landscapes, Near The End

(for the girl from Weirton)

The huge gob pile

along Weirton’s Harmon Creek,

a few straggling clumps of broom sage

bearding its blackened sides,

The fresh roadcut for WV Route 2 along the river

blasting away the green hillsides I’d seen

since a kid from Steubenville,

Tarry oil stains on river stones

round as poisoned biscuits

at the foot of Market Street,

New fracking wells

scabbing the river bottoms

and bulldozed terraces

where once skylarks

shot into the air

in song, and tumbled,

yellowgold

against the azure

of the sky,

madonnas

a-wing, sweet-

throated.

- Hague is known to use his poetry to bear on political or social issues. This began in earnest after he joined a group of activist writers known as the Southern Appalachian Writers Cooperative. Before that, he hadn’t given much thought to the social, political, and cultural aspects of writing poetry. Reading Wendell Berry, however, made it clear to him that not only is eating a political act, but so is just about everything else, especially those activities that entangle us with the natural world—travel, shopping, gathering in large numbers in cities, abandoning rural communities. Anyone driving south on 1-71 from Columbus through the industrial agricultural expanses of central Ohio would have seen the sign: “Hell Is Real,” just down the road from another one which asks, “Where will you spend eternity?” Hague finds the blindness of the erectors of these signs to the chemical-based and GMO-fraught crops surrounding them to be outrageous; he took it personally and tried to turn the tables on such self-righteousness and addled thinking.

Hell Is Real

sign on I-71 South, Central Ohio, early 21st century

Pilgrims and patriots,

please notice to our left

six hundred thirty acres

of flatplate glaciated Creation

permanently deforested,

planted to monocultures

of GMO “corn” and “soybeans,”

fertilized with thousands of gallons

of petroleum-based,

war-ensured chemicals,

tamed by huge “Sodbusters,”

bastardized bulldozers.

Here tree lines are gone,

small creeks clogged,

kames and moraines

wiped out by years

of plowing and compaction;

here earthworms are extinct,

As soon may be

our saintly farmers,

soft-bodied things

who move inside

the climate-controlled cabs

of their earth-breaking machines,

Who every Sunday

point their fingers and

build signs against sin,

which clearly thrives somewhere

else, and must be brought to

the attention

of all of us traveling,

they must presume,

from Sodom

to Gomorrah.

–Saad Ghosn