Now on view at Gagosian Beverly Hills is a select collection of fourteen early works by one of Britain’s most influential practitioners of modern sculpture, the late Sir Anthony Caro. Not only does the gallery’s abundance of natural light beautifully illuminate the artist’s early works, but its truly expansive and open floor plan allow viewers to interact with the spaces in which Caro’s pieces are set as the artist intended.

Caro gained widespread attention in 1963 when his brightly painted abstract sculptures appeared in an exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Unlike his predecessors who were accustomed to the tradition of mounting their work upon the plinth, Caro chose to eradicate the pedestal and instead situate his sculptures on the gallery floor.

A radical departure from the way sculpture had thus far been shown, Caro’s rejection of a mount to ground his work was welcomed with mixed reaction but ultimately gained him recognition as an innovative revisionist of sculptural tradition in the twentieth century.

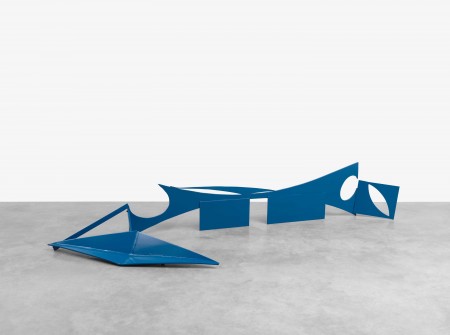

Photo Mike Bruce. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © Barford Sculptures Ltd. Anthony Caro, “Wide,” 1964, steel, and aluminium, painted 58 7/8 x 60 x 160 inches

While Caro helped to establish a new course for future developments in three-dimensional art, it wasn’t until he traveled to the U.S. in 1959 that he began to explore what became his pioneering approach to form, color, and presentation. Prior, he had worked for two years at Much Hadham, under the tutelage of Henry Moore.

While assisting Moore with his monumentally sized and semi-abstract figurative works in bronze, Caro didn’t only gain the opportunity to witness the sculptor’s process first hand, but the time he spent in Moore’s studio provided him with a profound learning experience and the introduction to genres with which he was unfamiliar, such as surrealism and cubism, among others.

It is clear that this experience broadened Caro’s artistic vocabulary and was crucially imperative to his development as a sculptor. Exposure to such, however, wasn’t the only catalyst worthy of prompting Caro to contort the figure (his primary subject throughout the 1950s), but it is what ultimately cultivated his interest in exploring abstraction.

Visiting the States is what appears to have had the greatest impact on Caro. Upon his first visit, he met with critic Clemet Greenberg and cultivated relationships with various painters, such as Kenneth Noland and Helen Frankenthaler, both of who, among others, contributed to the impetus that would forever change the trajectory of Caro’s path. Most influential, however, were David Smith’s innovative works that blurred the lines between sculpture and painting.

When Caro returned to London in 1960, he was immediately moved to construct his first non-referential, abstract piece, which he welded together out of scrap metal and then painted a bright color. From there, his vision grew as did the size of his sculptures, and not just vertically but horizontally as well.

“Month of May” (1963) is one of the larger pieces included in this extraordinary compilation of Caro’s early sculptures prepared in close collaboration with the Anthony Caro studio. Coated in a vibrant palette of purple, orange, and green, the piece, constructed from steel and aluminum, is exemplary of Caro’s capacity for “arousing an array of kinaesthetic responses,” as observed by Clive Ashwin for Studio International.

Making art a part of the space it occupies was clearly one of Caro’s objectives. Another work on exhibit that elucidates Caro’s aim to purport a communal spirit is “First National” (1964). The sculpture, like “Month of May,” compels its audience to move around the piece and examine its constituents from various perspectives. In doing so, viewers gain more than just a visual clarity of the steel painted sculpture but find themselves suspending critical thought in an effort to enjoy what Paul Caro describes as the true “abstract language of simple form.”

The fact that none of the works on view allude to any one specific object or thing is reflective of Caro’s improvisational approach. In his attempt to achieve “pure intelligence,” Caro relied upon an air of spontaneity to create each of his sculptures throughout his practice.

On view for the first time, “Purling” (1969) exhibits the essence of the exact lyrical ease that Caro sought to achieve by taking an extemporaneous approach in the construction of each of his works. Through a seemingly organic process, Caro continuously worked to manipulate the components or each of his sculptures, often attaching, removing, and then reattaching each of them, until configuring an arrangement that he felt emitted an aura of refinement.

While Caro is credited as a leading innovator of modern sculpture, it is impossible to forego the acknowledgement of Smith’s contribution to his work. While the artists knew each other for the two years, “the bright[ly] painted angular steel abstractions with which [Caro] made his name [are indicative of] a direct riposte to Smith,” as offered by Tim Adams for The Guardian.

After Smith’s untimely death in 1965, Caro purchased the entire contents of his sculptural scrapyard in the U.S. and then had it shipped to Hampstead for his personal use. One particular piece in this exhibition, in fact, is completely constructed from steel Caro sourced from Smith’s estate. The sculpture, entitled “Drift” (1970), is unique in that it features the pear shape, which Smith often borrowed from cubism.

Photo Mike Bruce. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery © Barford Sculptures Ltd. Anthony Caro, “Drift,” 1970, stainless steel and steel, painted 29 1/2 x 168 1/8x 48 inches

“Drift” is also distinct for its three points of reference. Again, Caro’s regard for his viewer’s vantage point is understood as a crucial component to Caro’s work. Viewers can’t help but to do as the title suggests and drift their gaze from one point of the piece to another.

In addition to Caro’s larger works that fill the gallery’s ground floor are a select few of his Table Pieces, which occupy the gallery’s second floor. While modest in scale, these sculptures follow within the same oeuvre of his larger ones.

Crafted in such a way that these works must hang over the edge of a supporting surface, they reiterate the dynamic that results when the surface upon which a sculpture is placed becomes integral to the sculpture itself. Impossible to ignore is the horizontal plane of the table, which runs through each piece. This interaction, between plane and sculpture, doesn’t only assert a distinct intimacy, but it clearly illustrates just how crucial the reliance of one is upon the other.

Caro was intent on creating a body of work that didn’t just play to his spectator’s senses but activated various parts of the brain that weren’t commonly energized. Anthony Caro: Works from the 1960s achieves this goal. Not only is the exhibition visually stunning, but it proves successful in that it intellectually challenges viewers by availing the space needed to truly explore each of Caro’s sculptures from a variety of perspectives.

Accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with a new essay by Tim Marlow and a key text by Rosaline Krauss, the exhibition is scheduled to run through May 30.

–Anise Stevens