Photographer Brad Austin Smith’s body of work contains a lot of bodies, including his own.

One of his more iconic black-and-white images is of his unclothed body classically posed – reminiscent of a Michelangelo marble sculpture. He was in a bathtub that was for sale inside what now is the grand Cincinnatian Hotel, but then was a seedy transient hotel awaiting its Cinderella transformation.

The inhabitants no longer were living in the building and owners were selling off contents of the building, including the bathtub, which was marked to go for $75.

“So I would go into every room and shut the door and lock it,” Smith explains about the bathtub image, one of his lifetime favorites.

“This was in a bathroom. So there wasn’t a lock on this door,” he says. “And I knew I wanted to make this image. So I pushed my camera bag up against the door, and there were other people who were walking around, buying the contents of the building.

“And I was on the top floor,” he adds. “I didn’t really hear a lot of people around, but I was concentrating on my own photographic stuff – stops and shutter speeds – and so a woman comes, and she pushes the door open like this much, and all she can see – and the place is spooky anyway – but all she can see is a naked man jumping up out of the bathtub. She screams.”

The woman demands: “‘What are you doing in there?’ I’m like, ‘I’m taking pictures.’”

This information did not appease her.

“But I know that nothing I can say is going to make it right for her,” he says. “She’s never going to understand that I’m doing this artistic thing, whatever, doing self-portraits. So I say, ‘I’m taking pictures.’ And she’s like, ‘Why are you taking naked photographs?’ And I’m like, ‘Just nevermind. Would you just leave me alone?’

“Believe whatever you need to believe. Just leave me alone,” he decides. “So she shuts the door. And there were guards at the entrance of the building to prevent people from stealing things. So they’d always see me going in with my camera and tripod, and whatnot. They never said anything, but every time they’d look at me, and a couple of times some of them would say to me, ‘Have a good time, sir.’ So she clearly went back and told someone about my nakedness in the bathtub. But they never said anything. But I took models in there, too.”

Making portraits of yourself, in often dark and gloomy places, can be tricky work. He had to pre-visualize the shot and get himself in position before the camera’s 12-second timer went off. His images were made on film, so he wouldn’t know how successful the images were in those days until they revealed themselves in the darkroom. Sometimes he would leap from the shot before the image was complete, leaving a ghostly transparency to his body.

Decades later, the image makes at least two impressions on the viewer: The luminosity of his body and the dingy bathtub, and the quality of the abs of this man, whose face is obscured.

In that same building, he captured another image of himself lying on a floor beneath a window. On that particular day he broke up a feather pillow and covered his body with the contents: “It was one of the hottest days of the year, so these feathers stuck to my body like glue,” Smith says.

In the photo, the feathers look like a moldy substance and obscure his genitals, leaving his body to look like a moldering corpse in a darkened, early 20th century apartment.

In the years from 1983 to 2000, Smith haunted vacant buildings throughout Cincinnati, and isolated waterways somewhere, capturing images of himself, often crouched in classical poses, images of everyman, isolated in storehouses, empty places, even inside a refrigerator. And while he’s always nude, these photos manage to be erotic, yet not sexual.

That’s not to say none of his images throughout the decades are about sex. In fact, it can be said that Brad Austin Smith, as a curator, nearly set off warning bells months before some homoerotic images by Robert Mapplethorpe triggered local prosecutions involving the Contemporary Arts Center that put the city in a worldwide spotlight.

One of his newer works, a black-and-white diptych of a man and woman manually stimulating each other while facing the viewer, may yet stir controversy, when the Contemporary Arts Center hosts a Mapplethorpe + 25 exhibit. Smith hopes Cincinnati has grown beyond that. But he’s interested to see what happens.

Modest Photo Beginnings

Before all that, Smith first learned about photography at Anderson High School. Smith, part of the Class of 1975, says he enjoyed making photographs.

“I took a couple of photo classes, and I really liked it then,” he says. “But my camera was stolen. So without a camera, it’s hard to take pictures. So I gave it up.”

“Plus,” he says, “I didn’t know how to make a living out of doing photography. It was just something I enjoyed doing. So then I worked for my father off and on, and did a bunch of odd jobs. I call it, “I was trying to figure out what I didn’t want to do for the rest of my life.”

He had creative parents, both now deceased. His mother, Cynthia Bauer, loved art, and painted. His father, Don Smith, also had a creative profession: He built and designed hydroplane boats, and he raced them in the ‘60s.

“So that part of his work was certainly artistic,” Smith says. “Not something you’d show in a gallery, but designing your own hydroplane boats, there’s certainly a craft to that.”

“My mother was into art, and she exposed us a lot to art,” says Smith, who lived on a farm near Eight Mile Road and Ohio 32, and recalls skinny-dipping in several pools across the township.

Smith worked at Kenner, in the toy shop, when the company was in the Kroger building. He drove a truck and did some electrical work. He also worked for his dad, who built and repaired boats.

“That work was kind-of enjoyable, but he was a hard person to work for,” Smith says. “He was hard on me because I was his son.”

“Probably in my early 20s I bought another camera, a Nikon, and started taking photos, and figured out it was something I really did enjoy,” Smith says. “So fast forward, taking photos for a few years, I got a job as a photo assistant at a commercial photo studio, and did that for several years, and then started my own business in ’87.”

He moved into a roof-level Court Street apartment and studio in 1983. He sometimes would pull his futon out onto the rooftop and sleep under the stars above his current studio, and hosted large rooftop parties there.

“It was a different time, in the ‘80s,” he muses.

In about 1988, the level below him became available and he rented that, about quadrupling his studio’s space. He later subleased the upstairs to the band Over the Rhine. He still occupies the studio, but no longer lives there.

“Living and working downtown, I’ve seen a lot of change over the years, definitely all for the better,” he says. “Court Street was a little rough in the ‘80s. There were dive bars, one across the street. There was a dive bar below this area. Definitely, it’s all positive, all the things that have happened. Really, to be honest, I think Over the Rhine turned around so quickly, I’m amazed at it.”

“When I opened my own business, I did commercial work, editorial work for magazines, and I’ve always done fine-arts stuff,” he says. “Even when I started work as a photo assistant, I worked long hours, kind of being a photo slave. I learned a lot. But I could see what I really got enjoyment out of, and it was really making my own pictures.”

On his own time, “I started out doing street photography in Over-the-Rhine and the East End.”

Using a 4-by-5-inch, large-format camera, he would set up his camera and wait for images that interested him, he says. “I’d ask everyone’s permission, because you can’t sneak up on someone with a 4-by-5 camera, on a tripod. If they said yes, I’d set up and wait ‘til they got back to doing what they were doing before I asked to take their picture. If there was someone who didn’t want to be in the photo, I’d just say, ‘No problem, you’re just going to have to skooch away, because nine of the 10 of you have said yes.’”

Some days, people weren’t outside “or it just wasn’t happening. So then I started photographing myself. I’m kind-of the easiest model I have: I’m always there. I don’t talk back to myself, too much. I enjoy the thought process of self portraits, because you have to pre-visualize.”

His artistic efforts were supported the years by grants and fellowships from the City of Cincinnati and Summerfair, and fellowships from the Ohio Arts Council.

These days, Smith shoots almost exclusively digital, but he loved the process of developing in a darkroom.

“With film, you could shoot a Polaroid, but those only told you so much,” he says. “Really, processing your film and holding the wet film up to the light, that was a joy, to know if you got the shot or not. Not only with self-portraits, but shooting in general. Processing the film. Certainly, making the prints, then you know if everything’s in focus, and if the light’s good. But holding that wet film up to the light is the real joy you got.”

He dabbled in digital in the early 2000s, and essentially made the switch to that format in 2006.

“My eyes aren’t as good as they used to be. A dark room? It’s dark in there,” he says with a chuckle. “Let’s just say the dark room has somewhat lost its appeal for me. I still love black-and-white silver prints made in the dark room. There’s really no comparison to digital prints, even though you can get pretty decent digital prints. But black-and-white prints on fiber-based paper, made in the dark room? There’s just something that’s always going to hold a special place in my heart.”

Street Photos and Social Documentary

He’s done several projects of social documentary work, others of street photos, including in Over the Rhine, the East End and areas of the West Side.

With the social documentary, he started relationships in the summer while people were outside.

“It’s easy to see people outside and ask if you can photograph them. That’s the easy part,” he says. “The hard part is in the winter, because their doors are shut. You can’t knock on a door and say, ‘Hi, can I take your picture?’ No, that’s never going to happen, so I knew that I had to establish a relationship with these people before winter, before those doors shut. So I started photographing them, and taking prints back. That’s something I’ve always liked to do.”

He documented the area along River Road and Sayler Park, showing people in their homes, their yards, and in bars.

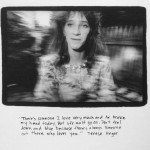

His most controversial street photos were in a collection called “Hustlers,” in which he photographed prostitutes and pimps in Over-the-Rhine and other haunts.

In the images, the prostitutes “were just on the street, just hanging out,” he says. “I had them write in my journal at the same time I photographed them, so you can see into their head a little bit more than just a still photograph would be. It was never a dull moment. Walnut Street was the busy street then. McMicken, kind of Lower Price Hill, a little bit in Covington. It kind of moved around. When vice would bust them on Walnut, they’d move over to Vine.”

“With the prostitutes, I asked everyone’s permission,” he says, “I didn’t want to sneak up on someone. I didn’t want to photograph someone who wasn’t a prostitute, so I would talk to them a little bit first, explain to them what needed to happen. I needed to take their picture, they needed to write in my journal, and they needed to sign a release. Those three things needed to happen. And then I’d say, ‘What do you expect to get out of it?’ Sometimes they’d want $50. I’m like, ‘I can give you some money, I can’t give you that much.’ There was a negotiation.”

What was his rejection rate?

“A fair amount of people said yes,” he says.

“For me, the camera is a kind of way to explore, to find out things,” he says. “Like prostitution, I noticed that there were, because I would park my car up in Over-the-Rhine. I noticed there were like twice as many prostitutes on the street as the year before, and so in my mind, what was the cause of it? It was crack. It was when crack came to town. But then carrying my journal let me see into their heads, just a glimpse, because sometimes they’d write only one sentence.”

“This was never a dull moment on the street,” he says. “I got two grants from the state of Ohio, in ’92 and ’94, for that project.”

One woman unexpectedly removed her shirt out in the street while he caught her image. In another photo, a pimp ominously points a gun at the camera. Not to worry, Smith says. The man promised the gun wasn’t loaded.

“I actually knew him a little bit, but that is trust there,” Smith concedes.

Some of the words the women wrote were as poignant as their photos.

“There’s someone I love very much and he broke my head today,” one streetwalker wrote. “But life must go on. Don’t feel down and blue because there’s always someone out there who loves you.”

Another wrote: “Is there a hell, or are we already living in it?”

“I did this (the Hustlers work) for four years, and for me, different projects, they kind-of run their course,” he says. “If I don’t feel like I’m making any new pictures or there’s anything else for me to learn, or to find out, that’s kind of time to put a project to bed.”

Before ending the Hustlers work, he had bigger-city aspirations.

“I thought, ‘I’m ready to take this on the road,’ so I went to New York, thinking I’m ready to shoot prostitutes in New York,” he says. But, “Kind of going into Harlem and whatnot, I realized, ‘I’m not ready for that.’ Part of it is I know Over-the-Rhine. I know the areas that are not safe to be in at night. New York was something totally foreign to me, so I didn’t even take a picture of prostitutes in New York.

More Sexual Work

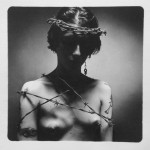

Then there’s what he calls “the S&M stuff.”

“I’m not into it, but there’s a curiosity there,” he says. “What is it about pain that’s pleasurable?”

In one of his more memorable images, a nude woman wears a crown of barbed wire, with more of the wire enwrapping her, pricking into her skin.

“This woman … so this was my idea to have the barbed wire,” Smith says. “I would have never pinched it so tight, but she knew what I was after. She was like, ‘No, go ahead and tighten that up.’ Because it drew some blood, but that was fine with her. But this image I think is one of the most powerful from that series.”

He got most of his models by word of mouth through friends, which was better than using Craigslist.

“I put ads in Craigslist, and that kind of opens up the door to sleazy stuff. So you just never know who’s going to walk through the door,” he says. “I’d explain to everyone: This is about the photographic process. This is not about something that you think may or may not happen, because it’s only about making art. So don’t get preconceived ideas about whatever you want.”

“So nude models, a lot of them are exhibitionists, and I’m totally OK with that,” he says. “I would only give these people prints of my work, which is worth way more than I could pay them,” he says.

“But if somebody’s an exhibitionist and they enjoy doing that work, that’s just a bonus for them. I’m totally fine with that. I’ve had nude models come and walk up to the windows, and I’m like, ‘Alright, I don’t want to get in trouble here. Old ladies live across the street and whatnot. I don’t want to freak them out.’”

“There was one guy, I photographed him quite a bit, and he had a good sense of humor, but he was always putting innuendoes out there,” Smith says. “And I was straightforward with him. Again, this is only about art, and not about what may or may not happen. He never wanted money, but he loved getting the prints. And he was an exhibitionist, but he was always putting innuendoes out there, to see if I would pick up on it. I’d say no, no, that’s not going to happen.”

Lately, he’s been doing less figure work and more social documentary, such as his collection of West Siders with American flags. That series started years ago when he moved to Price Hill and noticed how many flags there were there. He’s also been shooting photos from his 1960 Buick of scenes that are framed by the car’s windows.

Mapplethorpe + 25

“I will say that I do self-censor my work, because I know Cincinnati’s a conservative climate, if you will,” Smith says. “I know about Mapplethorpe. I curated a show at CAGE (Cincinnati Artists Group Effort) art gallery, a male nude photographic art show, six months before Mapplethorpe. WLW and WSAI kind of picked up on the male nude show and it received a fair amount of negative publicity.

“Someone came and reported it to the police as being offensive,” he recalls. “The vice squad, they came down and saw the show. They said they didn’t really see anything that offensive, but if they continued to get complaints, that they would have to do something about it. Thankfully, that never happened. That being said, it was the most well-attended show ever at the gallery.

“So that was kind-of the pre-hoopla (to Mapplethorpe), never envisioning what was going to happen with Mapplethorpe,” he says. “That was just crazy, just blew up. Certainly, I went to the opening, and I really liked Mapplethorpe’s work, but for me, the X portfolio, which was the most controversial stuff, some of it’s not really my cup of tea, but you don’t have to look at it if you don’t want to. You don’t even have to go in that room if it’s offensive.”

“So really, the whole Mapplethorpe thing, I did really like his work, but it was more about freedom of expression and whether or not government should have a say in what we should see and what we shouldn’t see,” he says. “That part was really important to me. And certainly a big win for the CAC and (its director) Dennis Barrie.

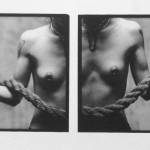

In his black-and-white image that will be part of the Mapplethorpe + 25 exhibit, a man and his female partner seem isolated – in part because each is separated within the diptych format – as they sexually manipulate the other. The man is aroused.

“It’s about two people masturbating, so it’s safe sex, but they’re also kind of disconnected,” he says. “I wanted a diptych, not just show it in one photograph, have the two separate images making one.

“The print is a lovely print, in my mind,” Smith says. “I hope it’s well received. I did ask my curator how far could I push the boundaries, and she said, ‘There’s no limits.’”

“And I said, ‘What if it’s controversial?’” he added. “She said, ‘They might have to put it in a back room with a disclaimer.’ In my mind, that sounds like Mapplethorpe. We’ll see if that happens. I hope it doesn’t. But if it does, I’m OK with that.”

Some of his work, he has never shown, out of self-censorship, with a realization that he doesn’t want to harm relationships with his corporate clients.

“I’m a realist. I’m an artist, but I also know how I make money,” he says. “When I say self-censorship, part of it is the whole Simon Leis stuff, but some of this more erotic stuff, I couldn’t really show it…. It would have an adverse effect on my commercial photography.”

“I love photography,” Smith says. “I still love it as much as when I first started doing it back in the ‘70s. I don’t love all the business aspects of it, because there’s a lot of different hats you have to wear, but actually making pictures? It still excites me as much as it did back then.

“I still love going to exhibitions, I love showing my work,” he adds. “I’m very fortunate to be one of the people that really enjoys their job. If you like what you do, it makes it seem a lot less like work. My wife, Suzanne, works with me, and she’s been with me since 2000.”

They married 10 years ago, and now live in Westwood. He has two adult children, Ian and Sienna.

–Mike Rutledge