A photograph of a black man’s flaccid, uncircumcised penis exposed through a three-piece suit may best represent the themes of sexuality, race, class and style that pervades his work. The photograph, titled “Man in Polyester Suit,” possesses a startling clarity and crispness that makes it seem somehow commercial, a glossy advertisement for the turbulent restraint and inherent eroticism of ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE: artist, provocateur, lover, brand. It also sold for $478,000 last month, a sign of increasing commodification and, one supposes, cultural legacy of Mapplethorpe’s work.

Of course the photo wasn’t always commercial. It certainly didn’t sell to Cincinnati in 1990, when an obscenity trial spurred by Mapplethorpe’s work in an exhibit at the Contemporary Art Museum in Cincinnati led to a momentous conversation about what defined art, and what kind of art taxpayer dollars could fund. The exhibit, titled The Perfect Moment, became a watershed one when the museum was acquitted, winning the “war on art,” as the New York Times reported.

There are the obvious questions about Robert Mapplethorpe’s polarizing 1990 exhibit at the CAC, which, along with a more traditional retrospective, enveloped images of flowers, portraits of black men and S&M in three portfolios titled X, Y, and Z. How exactly did The Perfect Moment remold America’s perceptions of challenging art? Why did this happen in Cincinnati, and not in the handful of cities the exhibit was displayed in? Could this happen today? In a country shellshocked by terrorism, increasing racial unrest, a drug epidemic and countless systems that are failing us, does anyone even care enough about art to think so seriously about a single exhibit? But these inquiries cannot be answered so straightforwardly. Still, an ambitious symposium at the CAC, which marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of The Perfect Moment, attempted to unpack what remains of Mapplethorpe and his momentous, posthumous and controversial show: his legacy, his persona, his mythology and his art.

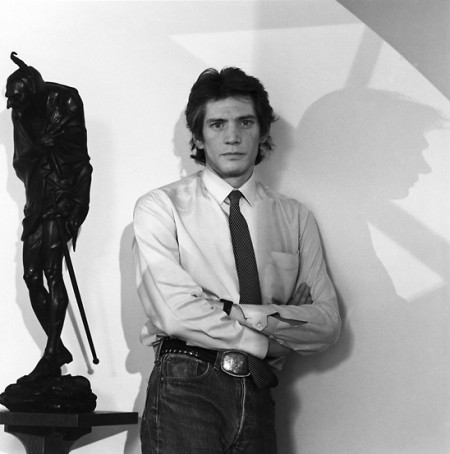

An opening keynote lecture from Germano Celant, an art historian, curator, critic and friend of Mapplethorpe, approached his oeuvre and biography (the two have been alloyed) with a scholarship and semiotic bent that might seem diametrically opposed with the rawness and rapturous life of Mapplethorpe’s output. But Celant’s is a vision, whether intentionally or not, of de-radicalization. Mapplethorpe’s highly aestheticized technique was his way of “taming” how he saw the world, and viewing the photographer’s work through the trammels of art history is just another way for us to tame Mapplethorpe. Celant so perfectly analyzed his art, placing it farther back in the canon next to Raphael and Michelangelo, that it makes us ask why anyone considered Mapplethorpe so innovative, so scandalizing. Those two words once may have synonymous in the art world, but certainly aren’t now, when we’ve become somewhat desensitized not just to “shocking” art, but to the world itself. Mapplethorpe’s artistic and social transgressions lie in the way he democratized what was worth photographing, and what could be seen as beautiful (as curator and writer Carol Squiers mentioned at one point in a panel, the biggest issue serious photography faced in the seventies until then had been the unprecedented use of color). Mapplethorpe’s fatal moral, political and artistic crime in The Perfect Moment, at least in Cincinnati, was not the homoerotic sadomasochistic imagery in the X portfolio, but that it dared to share its space with the high glamour and deceptive conventionality of flora and portraiture the other portfolios contained. His art became a political act that registered highly in a swing state like Ohio, especially in Cincinnati, a city notoriously divided in its ideologies. Add the fact that it was all presented in a museum space, an arbitrator of culture and taste, and it seems unsurprising there was such a reaction to the art.

How have Mapplethorpe’s photographs changed over time? It’s a question that went somewhat unanswered in the Curators Curate Mapplethorpe panel. Kevin Moore and expressed that as a curator, he often wondered what right he has to curate photographs made by and depicting an identity different from his own. Although Mapplethorpe didn’t want to be confined as a “gay photographer,” it’s hard to prove this hasn’t been the case today as we’ve watched his art change and thrive in the market. The commodification of contemporary art is something he surely grasped the extent of, but still, is the relevancy of Mapplethorpe’s work in the 21st century doomed to be based on its inaccessibility, its social cachet? It surely does not shock today, and though his photos were condemned as pornography in the nineties, the uncensored wilderness of the internet appears to have sanitized, or at least tamed, his more erotic images (the idea of “Man in Polyester Suit” actually being obscene was and still would be laughable if it wasn’t so disappointing). But his photos never primarily intended to shock—they intended to engage. Once they no longer do, they become almost meaningless. Today, when what most museums offer leaves us without any impression at all, with a shameful indifference, what Mapplethorpe was able to do in the nineties seems much more impressive. Then, it was impossible to view his images and not feel something.

A panel moderated by photography historian Philip Gefter and titled The Artist’s Circle and Studio provided fascinating, at times voyeuristic, personal access to Mapplethorpe as a human being, primarily because the panel members had no interest in forging any type of hagiography. Robert Sherman, the model famously and forever juxtaposed with Ken Moody in Mapplethorpe’s famous 1984 portrait, proved a captivating raconteur, walking us through several aspects of his relationship with the artist, from shootings (which vacillated from the improvisational to the meticulously posed) to their awkward consummation after meeting in one of Manhattan’s underground gay bars. As Sherman relayed his both fleeting and enduring experience with Mapplethorpe, he eventually led to somewhat of a revelation: that he had been, in the end, exploited, ignored after Mapplethorpe had forever taken his image for his art. Other panel members agreed that Mapplethorpe was far from perfect. If anything, he was more concerned with perfection, with establishing himself firmly within the canon.

The CAC’s The Perfect Moment anniversary symposium felt like one stray conversation, not necessarily giving us the answers to the questions we were asking, but that’s how these dialogues supposed to function. Not as closure, but as a kind of vaguer indulging of curiosities. This, too, is how art should be. Mapplethorpe knew that, and in our current time of anxiety, we need more Robert Mapplethorpes to start the kinds of conversations he sparked. Because the issues he explored, the identity politics, the dynamic between low and high, rich and poor, still exist—they just need new modes to operate in. The imperfection of Mapplethorpe’s moment stretches across America, waiting to pass. Yet some say Robert Mapplethorpe’s perfect moment happened a year after he died, when the war on art was won. But I think the moment is now, always now, ticking slowly down to zero.

—Zack Hatfield