Binary Harmonies was one of the more carefully assembled exhibitions of printmaking on display at this year’s Southern Graphics Conference International in the ever-eccentric Portland, Oregon. It opened on April second at Disjecta Contemporary Art Center. It didn’t even rain, and the exhibition was a joy. Dylan McManus curated the exhibition through the aesthetic interface of the post digital artist residency program and sustainable farm that he and his wife Bethany Ayres-McManus facilitate. McManus’ attitude toward the digital as hand extension is just that. McManus became the lead instructional technician in digital fabrication at SUNY New Paltz through teaching printmaking there. His adeptness with digital art interfacing through 3-D printing, CNC routing, and laser routing is evident in the contents of the exhibition, as well as in his own work, which was included.

To put it lightly, this show was powerfully populated. Dylan’s work is some of the only work in the exhibition that is immediately figurative. The works included are portraits, mostly of close friends, all burnt with a laser into discarded dollar bills. These Portraits of Recession seem to personalize the blight of neo-liberal capitalism, reclaiming the degradation of currency through its beautiful, and sterile destruction.

The entire show is predicated upon the incorporation of some digital aspect. Perhaps a degree removed from Dylan’s work is that of Miguel Aragón, a Ciudad Juarez native whose work addresses the Cartel Wars through a keenly tiered effect that’s deceivingly figurative. Aragón essentially hides murder directly in front of your face. This sleight of hand is mimetic of the governmental practice of suppressing news about the terrible murders occurring in Mexico. Aragón describes this aspect as giving formal weight to erasure both through content and technique. The images are altered digitally and then the defining lines of the original photograph are laser etched into cardboard. The cardboard is soaked and then printed like an etching. The water and burnt paper makes a stain when printed. Miguel calls them burnt residue embossments. The embossments curated into Binary Harmonies are done on bright white paper that delivers a calm gleaming like sunlit clouds. The gory horrors south of the border are subdued and effectively transmitted, transfiguring erasure into language, negation into creation, and catharsis into query.

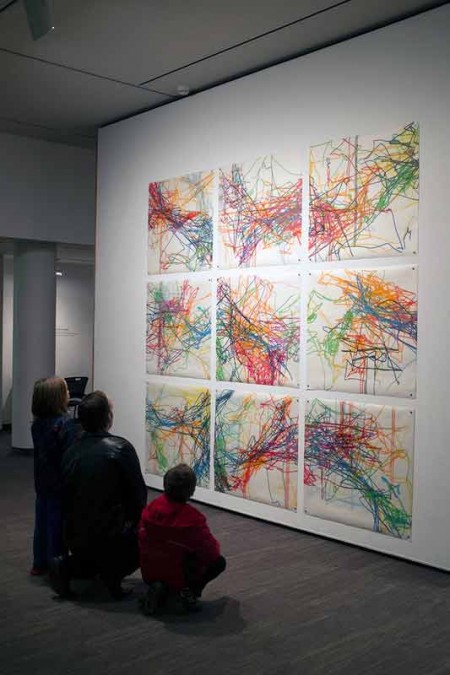

I was especially impressed by the one artist in the show with whom I was unfamiliar– and printmaking is a small community. Dana Potter is making exciting work that navigates the post digital like a scalpel releasing rainbows from inside a robot. She uses a computer to track her mouse pad movements. These tracks are then lasered into birch plywood. She prints the cut lines and their silhouettes and exhibits her matrasses also. Her mattresses are color coded to signify different computer programs, and some of the lines are very gangly. The cut lines are printed together on large sheets of mulberry, the prints hung without frame alongside the sculpturally spirited objects that impressed them into existence. The prints resemble the map of the London Underground rearranged a la Nicolas Krushenick. The line-centric forms of Potter’s work become politically visual meditations on quantifying the physical aspect of user interface with digital media in an effort to combat the capitalist motivation behind government endorsed corporate surveillance of the web. The cut lines, left coated in the oil based relief ink they’re printed with, develop a marvelous patina that makes you want to own that. This quality of the object effortlessly echoes Marshall McLuhan’s maxim “The medium is the message.”

Aaron Nelson’s installation of receipt printers with tickets hanging down like a Postmodern Rapunzel, offers the sterility of science understood through television. The tickets are printed with racist comments percolated through twitter and identified with keyword searches. The installation functions as a sort of sieve with no tricks and no sleeve, just pure racism alive and well. The transmission that occurs is a cold fact barrier that would deny apologists. The use of technology is once again seamlessly married to the political dedication of printing through the ages.

Jon Irving’s work orients self-portraiture at the nexus of alter ego and embarrassment. The character in Jon’s work is the Superior Model; effectively Irving carved out of linoleum without a face. Jon sometimes performs this character in conjunction with exhibited prints donning a business suit with relief printed patterning. The prints are a technical mixture of relief, screen-printing, and computer-generated imagery. The Superior Model is like the artist’s valence electron revolving through the separate worlds of the business professional and artist both rooted in the riveting context of New York City. Jon’s work presents the palatable substance of human folly through his own body. The prints are also beautifully sparse breathing the personality of space onto the page, newly alive.

Tim Dooley and Aaron Wilson present as the cooperative entity known as Midwest Pressed. The two have been making pure magic. They laser cut woodblocks into jigsaws and then ink the sections independently with transparent gradient swathes of color. The colors are varied dramatically as layers pile up in concert. The product is an explosion of vivid hues writhing like a giant gummy worm with Christmas lights inside it. Beautifully abstract, the work is relief without the gouge, no pun intended.

Ryan O’Malley’s work is an extrapolation into the realm of collographic printing. O’Malley’s newest body of work is called SHAPESHIFTER, the collagraphs are made from laser cut pieces derived of stenciled portraits of O’Malley’s closest friends. The laser cut facial futures are liberated from their original context into reconstitutions based in pattern, animal physicality, and pursuits purely formal. In O’Malley’s graphite clad collographs, mounted on panels, identity is suspended through the static of mash-up, and nostalgic fondness transcends into the frenetically bizarre realm. The human is conflated with the binary sterility of technology, the compositions reflective of the human tendency to find and project pattern.

John Hitchcock’s screen-prints were also featured. The images are digitally derived through the process of screen-printing. Hitchcock’s work extends his understanding of his Native American identity as it interrelates with the deep narrative and conversation of colonialism, appropriation, genocide, and subsequent amnesia with which contemporary North America is saturated. His imagery distills cultural loss into symbol, and asserts a conversational tone that chooses a politics of common history rather than a politics of difference. There is an embrasive quality to the work that postulates thorough equity despite perceived extremes of difference, that history is categorically not incongruous, but shared. Hitchcock is instigating critical thought through thoughtful emblems reimaging the past.

Endless Editions is the collaborative entity of Paul John and Anthony Tino, both New Paltz Alums. The works selected for this exhibition are collaborations with Bosnian artist Zebediah Keneally on a series of drawings reproduced through the Japanese Risograph. Originally designed for high volume photocopying, the Risograph has been revived in the publishing of zines and other fine arts applications of the post digital age. Its personality is similar to that of analogue recording and music. It is both novel and desirable because it uses real ink, and extends the democratic aspect of images. “Kill All HiPPIES,” the image proclaims in black and pink.

The exhibition is defined by a balance between visual pleasure and satisfying content both camped in critical thought that rallies against the powers of oppression. Importantly, the exhibition challenges the nostalgic luddite to realize that digital and new media are here to stay and that they can be successfully harnessed within and outside the archaic world of printmaking. It was truly refreshing and also necessary to see the post digital and the archaic tied together so succinctly within the context of a conference.

–Jack Wood