If your appetite for Van Gogh was whetted by the five wonderful canvases shown at the Taft Museum’s current “Impressions of Landscape,” you should promptly schedule a road trip to Chicago where the Art Institute is showing “Van Gogh’s Bedrooms,” an exhibition designed to contextualize the three different versions Van Gogh painted of “The Bedroom” in his house in Arles in the late 1880s. This is the only venue in the world to see the show, which features some forty works, about half of which are from abroad (especially from Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum) and a quarter of which are from the Art Institute’s own fabulous collection of Post-Impressionists. This includes version number two of “The Bedroom,” the first one to have entered a public collection anywhere in the world, which found its way to Chicago as part of the same gift that included Seurat’s “La Grande Jatte.” Though the Van Gogh is in every way intimate and the Seurat is in every way monumental, it turns out that Van Gogh saw the Parisian pointillist as one of his most significant influences and touchstones.

It is sobering, in thinking about Van Gogh, to realize how short a career he had. He decided to be a painter in 1880 and before July of 1890 was over, he was dead, a suicide. In those ten years, he produced some nine hundred paintings plus over a thousand additional sketches and drawings. The Taft show’s Van Goghs focus on the work he did in Auvers where he went to give himself a respite from Arles in southern France, the site of The Yellow House whose bedroom provides the crux of Chicago’s exhibition. In that distant suburb of Paris, in a little over two months, Van Gogh produced, on average, more than a painting per day.

In Chicago’s construction of Van Gogh’s career, all roads lead to Arles. After spending two years absorbing all he could of the Paris scene, he fled the pressure and the high prices in search of a place he could call both his actual and his metaphorical home. (Van Gogh did a fair amount of fleeing in his life. As the show’s catalogue notes, in his blazingly short life of 37 years, he lived in 37 houses in 24 cities in 4 countries.) In Arles, he rented The Yellow House, where he hoped to establish “The Studio of the South,” where artists could live and work together and sort out what was truly most important about life and about the painting going on in Paris. And of those artists who might live and work together, he had in mind, chiefly, Gauguin. In many ways, The Yellow House in Arles was designed to be the perfect invitation, inspiration, and perhaps cage in which Van Gogh hoped to capture the slightly older artist. In the end, Gauguin—a man who knew a fair amount about fleeing himself—spent about two months living with Van Gogh. Soon both were on the road again, Van Gogh heading north and Gauguin to Tahiti.

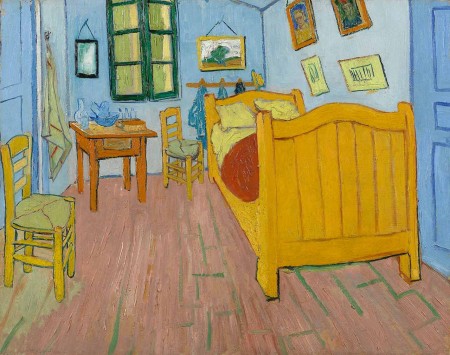

Had they spent more time together, Gauguin would have been with an artist who was just hitting his stride. As part of the buildup to the bedroom paintings, the Chicago show helps us see, almost to the moment, just when Van Gogh became Van Gogh—which is to say, when the Dutch Van Gogh became the French Van Gogh. It’s made visible in two pairs of shoes. Over his career, Van Gogh painted over a half dozen different versions of pairs of empty shoes. They constituted a highly suggestive subject, evoking the physically difficult domestic life of the working man and the haunting romance of things that are matched up two by two, a motif that seemed to be much on Van Gogh’s mind throughout his career. The shucked shoes provide a sense of wholeness and completeness, but also a sense of absence and the bereft. In 1887, he painted “A Pair of Shoes, One Shoe Upside Down,” which looks of a piece with his earlier work featuring impoverished Dutch workers with their sorrow and energy, and the grey-brown dinginess that defines their lives. In the same year, in Paris, he painted “A Pair of Boots,” and the difference is spectacular. Color is suddenly important: bright colors, lyric colors, soft colors. The first painting is a solemn document; the second is a still life with shoes taking the place of flowers or a good meal. To be sure, Van Gogh never abandoned his sense of himself as a painter who displayed his social concerns; we see more of that in his work than in any of the Impressionists and virtually any of the Post-Impressionists. But in Paris, he had learned what colors could do–not primarily Monet’s colors which uncannily capture the fleeting moment, but especially the more calculated colors of Seurat. (He may have drawn from Monet the possibility of seriality.) And from Seurat, Van Gogh also got new ideas about what brush strokes were and how they worked together while each stroke was still maintaining its autonomy, like pieces of a mosaic. He associated the independence of each mark on his canvas with his core values; he wrote to his brother in 1888 that “The Bedroom,” when compared to other recent paintings he had completed, is “simpler and more virile. No stippling, no hatching, nothing, the tints flat, but in harmony.”

In the same year, he painted “Grapes, Lemons, Pears, and Apples” (1887), which is remarkable for its circular organization. The fruit seems to sit on a cloud, surrounded by a halo. In the process, Van Gogh has released himself from the tyranny of the horizon line. It is interesting how many paintings in the exhibition display some degree of freedom from the horizontal, such as “Entrance to the Public Gardens in Arles” (1888). At the very end of his career, he returned aggressively to the horizontal with a series of double-wide panoramic landscapes (some of which are reproduced in the Taft’s Daubigny catalogue). But in the brief moment when Van Gogh found his style, the horizon—and the stability of vanishing point perspective—might be up for grabs.

It is also fair to say that the Chicago show couples its vision of Van Gogh triumphantly becoming Van Gogh with a clear and haunting vision of Van Gogh losing himself. Gauguin leaves The Yellow House and before too long, Van Gogh finds himself in other houses, less hospitable to his artistic dreams, as he undergoes a series of enforced committals and self-committals to various mental institutions. Four of the final paintings in the show are of the facades of these buildings or feature a haunting look down “A Corridor in the Asylum” (1889) with a distant figure furtively disappearing into one of its many doorways. Vanishing point perspective has rarely been used to more haunting effect. Perhaps it’s part of what he can hold onto. During some of these stretches, he was kept from art supplies of every sort.

This calls to mind a separate issue about the Chicago show: how remarkably and intensely biographical it is. Perhaps in large part because of the extraordinary care with which he communicated to his brother Theo, we are able to follow Van Gogh’s coming and goings in almost forensic detail. There are times when the wall labels are as meticulous as the Warren Report. We know on exactly what days he painted certain canvases. There is a certain thrill to be looking over an artist’s shoulder—or perhaps more accurately, to see him as his neighbors experienced him, in his rooms and on the streets—but it raises questions about what sorts of information we truly need when looking at paintings, what sorts of information we crave, and at what price those cravings get satisfied. We have come to accept that our appetites for biographical information will enable us to fashion the key that will unlock many, many doors in our understanding of works of art. Would we equally accept it as an explanation for what we ourselves do, think, and make? There are certainly other contexts that could have been brought to bear on the work. There is something a little sly, a little voyeuristic, a little creepy about the biographical emphasis. There is a limit to how much we should hold the Art Institute responsible for the work of Leo Burnett, its publicists. But on every bus in Chicago and in many store windows, there were posters for the show featuring a view of the bedroom through a keyhole. As a piece in Advertising Age noted: “Early on, the agency met with curator Gloria Groom to learn about her vision and inspiration. The team decided on a strategy of ‘Let Yourself In,’ a line that has been used on materials such as posters with keyholes revealing a close-up of Van Gogh or the room. ‘It’s a voyeuristic experience of Van Gogh’s life….’”

The exhibit traces Van Gogh’s footsteps as he comes to focus more and more on The Yellow House and his hope that he could live there productively and in the company of friends. We get a picture of a man who was both amiable and difficult, who could be excellent company and yet also very needy, demanding, quite possibly unclean, and, as a critic standing near me observed, generally impossible. David Getsy’s essay in the exhibition catalogue writes of Van Gogh’s “suffocating enthusiasm.” It’s possible to imagine the relief that Gauguin, as a former financier and privileged bohemian, might have felt when he put some miles between himself and Van Gogh. The show also serves to remind us that we are perfectly likely to come to no better than an equivocal understanding of something despite having a great deal of data about it. When we look through the metaphorical keyhole of the exhibition, what do we really see as the relationship between Van Gogh and Gauguin?

The curator’s take on that relationship is highlighted in the discussion of the contrasts between “Gauguin’s Chair” (1888) and “Van Gogh’s Chair” (1888). Gauguin’s chair is an elaborate thing, all in all, with knobbed arms and a curved back, and a colored seat. There are a couple of books on it and a lighted candle—the life of the mind and the light of inspiration? On the wall, a gas flame is lit. By contrast, Van Gogh’s chair is a simple matter of unfinished pine with what looks like a plain, woven straw seat with a pipe and a paper full of tobacco on it. Perhaps he needs a light? On the floor is a carton of onions. Some of this is easy: Gauguin’s chair is the master’s and Van Gogh’s is the pupil’s. But for all their apparent certainty, biographical readings can still lead us into more equivocal territory. The relationship is largely one of admiration and discipleship, but perhaps there is a passive-aggressive undertone to the contrast between the works. Gauguin’s chair seems to be in a darker room, in need of some artificial light, while Van Gogh’s seems to be in the bright corner of a well-illuminated room. Gauguin’s world is filled with intangibles—the pleasures of reading, the light of inspiration—while Van Gogh’s is marked by an appetite for tangible pleasures, homely but nourishing. Van Gogh was oddly both submissive and competitive.

This helps bring us to one of the greatest points of contention between Van Gogh and Gauguin, and brings us as well, at long last, to the bedrooms, for which the rest of the exhibit is a run-up. Van Gogh painted from life; Gauguin advocated painting from memory and the imagination. By the time he reached Tahiti, Gauguin went immediately to the mythic. (What might Van Gogh have found to paint in Polynesia?) Van Gogh might have argued that he limited himself to the actual, but he was keenly aware of the spiritual and the mysterious, and loved the opportunity to paint what was before him in such a way as to suggest the unseen. We experience this with his pairs of empty shoes, of course, or with his paintings of piles of novels which imply voracious but absent readers, or, in “The Bedroom” series, the empty chairs, the well-made bed, and all the things neatly hung: the paintings, the towel, the blank mirror. Each of the turn-of-the-century’s great artists played with the way that space was represented, generally flattening shapes and form. Van Gogh’s own relationship to space was especially complicated. In 1882, he excitedly described to his brother Theo how he had just caused a perspective frame to be crafted with the help of a blacksmith to facilitate his quick capturing—speed of execution was always important to Van Gogh—of the illusion of space. With “The Bedroom,” however, space is more complicated and while the picture has a tiled floor to help keep track of spatial recession, the floor seems to be taking a precipitous dip at the feet of the viewer. There is not a breath of moving air in the room, but at the same time, nothing is quite stable.

It is hard not to see some element of self-portraiture in “The Bedroom.” The catalogue notes that Petra Chu called it “Van Gogh’s most complex objectified self-image.” But the picture it offers of the artist is indirect. He had developed an interest—perhaps eventually an obsession—in arranging an overall decorative scheme for The Yellow House. Here this is not a pejorative term about a weakness, but a term denoting powerful restraint, painterly discipline, and strength of mind. You can’t make me turn this into a narrative. Perhaps this helps link his work to that of Bonnard and Vuillard whose interests in abstraction were sometimes manifested by their forgoing narrative in favor of an aesthetic whose source of power was the diffusion of focus that characterized the decorative. Van Gogh undertook a series of paintings of the park across the street from the house with the idea of having a decorative cycle of works he could put up on the walls to be called “The Poet’s Garden.” Still-lifes of sunflowers figured in as well, and, of course, there was “The Bedroom.” The walls of every room, public or private, had been planned out.

So when one asks what “The Bedroom” represents, some part of the answer must be that it was a part of an intellectual and artistic courtship of Gauguin with whom The Yellow House was to be shared. Everywhere Gauguin was to look, he would see homages to himself, indications of what sort of role he was to play and where and how he might play it, and maybe even some challenges to his own principles about life and art.

Above all, the purpose of the Chicago show is to bring together the three versions of “The Bedroom” to see what light they might shed on each other. To some extent because of the show, we now know with strong certainty that one version was painted in October 1888, a few days after Van Gogh moved into The Yellow House and a week before Gauguin joined him. The second version was painted about eleven months later, in part because of water damage to the first. A few weeks later, he painted the final version, which he sent as a gift to his mother. Van Gogh would have considered each work to be a different sort of work of art. He would have called the first a “croquis,” or sketch, though that was his term for a completed painting. The second was a “repetitition,” a thing that Van Gogh—and most 19th century painters—did a lot of. The third was a “reduction,” though in terms of actual size, it is only about a third smaller. Many of the most interesting differences can be traced to the strikingly different occasions and purposes of their creation. The first version was done in anticipation of Gauguin’s arrival; the second was done some eight months after Gauguin had decamped (he left the day after that business with the ear), during which interval Van Gogh had been hospitalized on four separate occasions; the third and final version might have been part of a desire to leave a record behind of the work he valued most. Ten months later he would be dead. He painted the first from life. Fearing that it had been damaged, the second and third were done by copying the first, and were basically paintings of paintings, guided by his memories and feelings about the first which led him to a series of revisions that the exhibit suggestively and meticulously calls our attention to. Gauguin and Van Gogh had argued about whether art should be done from life, in the moment, or from recollections and visions. With “The Bedroom,” they were both right.

Decades ago, a show like this would have been an exercise in hard-nosed connoisseurship. In 2016, the exhibition is an example of hard-edged science working in tandem with the arts and humanities. By examining each part of each painting, the exhibition can tell us the order in which the versions were done. It can see the differences in how Van Gogh outlines each version of the composition before filling the outlines in. There is an alcove in which museum-goers can sit and watch on a triple screen as various details, some extraordinarily minute, are zoomed in on much larger than life. There is a CSI quality to some of the scientific work. Tiny traces of charcoal were found on one version or other, telling us about the underdrawing, or fragments of newsprint were found from where a still sticky canvas was wrapped with the nearest material Van Gogh had handy. There is a second alcove dedicated to the research that has been done on Van Gogh’s faded colors. He painted with some of art world’s most fugitive pigments, including geranium lake and cochineal lake. But in the alcove, you can sit and watch the works being digitally returned to their original colors, giving us all the chance to “see” the paintings as they would have looked the moment Van Gogh put his brush down for the day. He is restored to us as a color symbolist whose true colors we could otherwise no longer appreciate. The principles of science and color are working hand in hand with the principles of composition and mood. Seurat would have nodded.

Another thing you’ll see if you go to Chicago for the show is the back of many, many, many people’s heads. Though there is timed admission to the galleries, negotiating the crowds in some of the museum’s narrower spaces takes patience and strategy, as people take forever to read the opening text panels on the wall, unaccountably zoom past amazing canvases, and slow down in unison in front of works featured in the audio guide. Like certain highways or subway systems, it makes you wish there could be an express lane for those who want to be on their way with reasonable efficiency and a local lane for those who don’t mind making every stop. There are so many reasons nowadays to revere the popularity of a remarkable show, but also so many reasons not to. Too cranky? Well, then there are the selfies. It is interesting and important to think about Van Gogh’s appropriations of Hiroshige, Daumier, Millet, Dore. It would take the patience of a bored museum guard to ponder the significance of all the visitors’ cell phone appropriations of Van Gogh. Crowds of people were photobombing “The Bedroom”; it was hard not to think of Van Gogh wishing that Gauguin would have photobombed it, just once. This must be how the animals in the zoo feel.

Look: I am not proud of how ambivalent I feel about the democratization of the fine arts. I felt irrelevant, sedate, severe, and Apollonian to so many other people’s gleeful Dionysian energies. It’s okay, it’s not you; it’s me. Perhaps the audience is taking a cue from the publicists who helped create and stoke the voyeuristic expectations. What do you expect to see and how should you be expected to behave when you screw your eye to the keyhole? Perhaps people are drawn these days to all the places where there are crowds and then feel the human need to stand out from them; the combination of crowds and selfies is a non-paradox. And I understand that the crowd’s simultaneous presence and relative indifference to the cause of their gathering is a judgment on our culture that cannot be appealed. It may be that some people are trying to work out their edgy self-definition as heirs to modernity. But to many museum-goers, modernism is no more intrinsically close to their concerns than Hellenistic sculpture or medieval illumination. Still, every customer through the door of every exhibition at every museum represents a precious chance to teach people how to experience art more intensely and to make more out of the whole loud, chaotic, exhausting process. Clearly there has been nothing like a consensus reached yet on how to do that.