If you are in New York before August 7, see Turner’s Whaling Pictures at the Metropolitan Museum. Turner exhibited Whalers and The Whale Ship at London’s Royal Academy in 1845, followed by “Hurrah! for the Whaler Erebus! Another Fish!” and Whalers (Boiling Blubber) in 1846. The four works were unsold in Turner’s private gallery when Herman Melville visited London in November and December 1849. The current exhibition in New York is the first time the four paintings have ever been seen together in public. The centerpiece of the show is The Whale Ship, which the Metropolitan Museum acquired in 1896. The museum is celebrating the 120th anniversary of this acquisition by borrowing the other three paintings from the Tate Gallery in London.

J. M. W. Turner, The Whale Ship, oil on canvas, 1845. Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1896. Photo Courtesy New York Met.

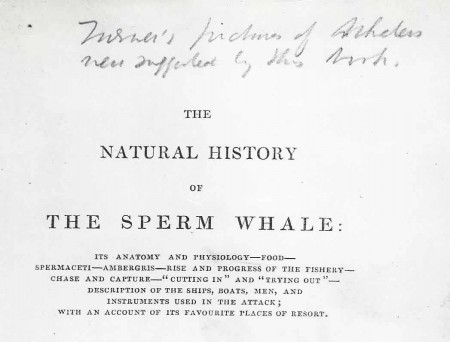

The exhibition at the Met is compact in space and expansive in imagination. One square room in the heart of the European Painting galleries houses the four whaling paintings, two late Turner watercolors, one earlier watercolor, a pencil drawing of the painter late in life, the engraving of one of the whaling scenes, several whale oil lamps, and a very large harpoon. The room also displays three books and two large wall panels related to Melville’s Moby-Dick. The books are in a glass case in the center of the gallery directly behind the partition on which The Whale Ship is hanging. They are the first thing you see if you enter the room from its other doorway. The book on the left is Melville’s copy of Thomas Beale’s Natural History of the Sperm Whale, published in 1839 and borrowed from the Houghton Reading Room at Harvard University for this exhibition. Melville acquired the book in July 1850, when he was well into the writing of Moby-Dick. He wrote on its title page that “Turner’s pictures of Whalers were suggested by this book.”

Annotation on title page of Thomas Beale, Natural History of the Sperm Whale, 1839. From the Library of Herman Melville, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge. Author photo.

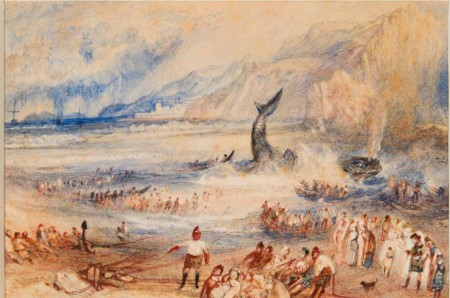

Because of the radically indistinct aesthetic of Turner’s late style, the references he made to Beale’s Natural History in the Royal Academy catalog helped his viewers discern the narrative sequence among the four whaling paintings. The paintings Turner exhibited in 1845 depict the “Chase and Capture” of the sperm whale (in the phrasing from Beale’s title page). In the 1845 Whalers on loan from the Tate, we see three whaleboats whose foremost whalers are about to toss their harpoons into the rising hump of a massive whale as a slate gray storm bears down upon them. In The Whale Ship, the whalers themselves have been tossed from their boats by the mortally wounded whale whose bleeding black head stains and shadows the sea. The two 1846 whaling oils are each dominated by striking atmospheric effects that situate human activity with the larger natural rhythms. Turner nevertheless takes care to depict both the “Cutting In and Trying Out” by which the whalers process the body of the whale they have chased and captured, first by severing the head from its body, then by boiling its blubber by fire. Standing before “Hurrah! for the Whaler Erebus! Another Fish!” (to the left of its 1846 companion in the installation at the Met), you can clearly see, in the middle distance on the right, the severed head of a sperm whale hanging above the ship in the intense solar glare. In Whalers (boiling Blubber) the body of the whale is being boiled in the try-works at the left; the smoke drifting through the naked spars of the ship is the last we see of the living body that was chased in Whalers and captured in The Whale Ship. On the right side of the solar glare in this painting, we see a second whale ship trapped deep in an ice pack, as indicated by Turner in the full title of the painting, Whalers (boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavoring to Extricate Themselves.

In Moby-Dick, Melville followed both Beale and Turner in creating a carefully structured sequence from the “Chase and Capture” through the “Cutting In and Trying Out.” In the novel, this sequence runs from chapters 47 and 61 (“The First Lowering” and “Stubb Kills a Whale”) through chapters 67 and 96 (“Cutting In” and “The Try-Works”). But Melville’s affinities with Beale and Turner go far beyond this structural similarity. Turner deepens the pictorial force of the bleeding head of the whale in The Whale Ship by relating it (in the Royal Academy catalog) to Beale’s description of a “massive sperm whale” who was chased and captured off Japan in August 1832 but whose corpse sank out of sight before the cutting in and tying out could begin. Melville echoes this irony by having the body of the old bull whale who is chased, captured, and killed in chapter 81 (“The Pequod meets the Virgin”) sink out of sight before its “cabinet” can be “rummaged.” In “The Sphynx,” three chapters after the “cutting in” of the whale that Stubb has killed, Melville depicts the severed head of that whale in a manner very similar to that of Turner in his Whaler Erebus painting of a few years earlier. “It was a black and hooded head; and hanging there in the midst of so intense a calm, it seemed the Sphynx’s in the desert.”

Detail, “Hurrah! for the Whaler Erebus! another Fish!,” oil on canvas, 1846. Tate Gallery, London, accepted as part of the Turner Bequest, 1856. Author photo.

The curators of the exhibition at the Met, in addition to displaying the copy of Beale’s book open to Melville’s annotation about “Turner’s pictures of Whalers,” address the degree to which Turner’s paintings may actually have influenced Moby-Dick in two large wall panels entitled “Melville and Turner.” The first panel explores what Melville is likely to have learned about Turner’s “pictures of Whalers” in London in 1849 even if he did not have an opportunity to see them in person. The curators suggest that the “most compelling affinities” between Moby-Dick and Turner’s paintings are to be found in Ishmael’s description of the painting in the Spouter-Inn at the beginning of chapter 3. Their second panel is devoted exclusively to generous quotations from that description. Ishmael wonders if the creator of this work had “endeavored to delineate chaos bewitched.” This fictional painting has “a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvelous painting meant.” Ishmael describes several features of the Spouter-Inn painting that have a particular affinity with The Whale Ship at the Met. Its water is a “nameless yeast.” The shape of the whale is “a long, limber, portentous black mass of something . . . in the picture’s midst.” Curator Alison Hokanson explores these and other affinities between Melville and Turner in her 48-page essay in the Spring 2016 issue of the museum’s Bulletin, giving generous credit to my book Melville and Turner: Spheres of Love and Fright, published in 1992.

I admire the way this beautifully conceived exhibition opens up the interdisciplinary relationship among Turner, Beale, and Melville without insisting on its specific results. The exploratory freedom it offers to its viewer is certainly one reason that Ken Johnson, reviewing the show in the June 3 issue of The New York Times, found Turner’s Whaling Pictures to be “an exceptionally thought-provoking exhibition.” He ends his review by suggesting that “it would be wonderful to think of Turner reading Moby-Dick and recognizing his own work in Ishmael’s own heated description. But Turner died in December 1851, just after the publication of Melville’s epic tragedy.”

Visitors from Cincinnati will not want to leave the show without seeing the small watercolor on the wall behind you to your left as you walk through the entrance leading to The Whale Ship. The Whale on Shore is one of ten Turner watercolors in the collection of the Taft Museum of Art. Only 4 x 6 inches, Turner created it to be engraved for an edition of writings by Sir Walter Scott in which it never appeared. Turner’s depiction of the stranded whale and the men who are attacking it closely follows a scene described by Scott in The Pirate, published in 1822. The whale we see fighting for its life is the first whale Turner is known to have drawn. It is the last one whose head and tail are both clearly seen.

J. M. W. Turner, The Whale on Shore, watercolor on paper, c. 1837. Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1931.382. Photo courtesy New York Met.

–Robert Wallace