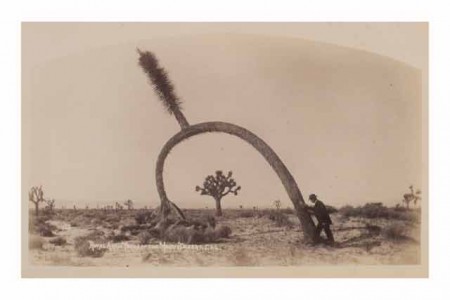

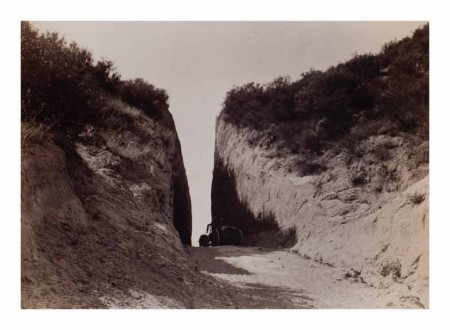

Photographer unknown, San Fernando Pass (now known as Newhall Pass), Santa Clarita, CA 1880s (from The American West)

Recently I took a road trip from the Queen City to the Motor City to see The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip at the Detroit Institute of Arts. On the way back I stopped at the Toledo Museum of Art to catch The American West: Photographs of a New Frontier.

Appropriately, The Open Road is a traveling exhibition, curated by David Campany and Denise Wolff for Aperture Foundation and is the companion to a quite large book of the same title. The American West (now closed) was a compilation of 70 photographs representing the evolution of photographing the Western United States, all drawn from the museum’s collection, and not intended to travel; no catalogue accompanies the exhibition.

The press release for The Open Road describes it as “the first exhibition and book to explore the story of the American photographic road trip & one of the most distinct, important and appealing themes of the medium” (perhaps the ampersand was meant to be a comma), tracing the trope to post-World War II, when “the American road trip began appearing prominently in literature, music, movies and photography.” Walker Evans’ and Edward Weston’s pre-war photographic travels through the country are cited as antecedents, but Swiss photographer Robert Frank’s 1955 photographic road trip across the U.S is the exhibition’s touchstone. Frank’s photographs were published in 1958 (initially in France) as the seminal photography book The Americans and inspired generations of photographers to hit the American road with their cameras. Correspondingly, three of the five non-American photographers included in the exhibition are French (Bernard Plossu) and Swiss (Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs); the fourth is Shinya Fujiwara from Japan (where most of the cameras have come from since) and the fifth listed is the extraordinary Dane, Jacob Holdt, although absent from the configuration in Detroit (more about Holdt later). Also included in the exhibition is Inge Morath, born in Austria but considered American, having lived in the US for 40 years, married to playwright Arthur Miller). In all,19 photographers are represented in the exhibition (although 18 at DIA and 34 in the book). They are Robert Frank, Ed Ruscha, Garry Winogrand, Inge Morath, William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Joel Meyerowitz, Jacob Holdt, Stephen Shore, Bernard Plossu, Victor Burgin, Joel Sternfeld, Alec Soth, Todd Hido, Shinya Fujiwara, Ryan McGinley, Justine Kurland, and Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs: A veritable who’s-who of the genre, if indeed a genre it is.

In attempting to establish the photographic road trip as a significant genre (and the American road trip apparently as its most significant sub-genre), another photographic genre looms large over the exhibition, one popularized throughout the same time period: street photography. Certainly that’s how one would characterize Garry Winogrand’s photographs had they been made on one of his walks in NYC rather than traveling in Texas, and it’s how Frank’s and others of these photographers’ work has been characterized in the past. The title, The Open Road, seems to suggest not just any road(s), but journeys into the vast expanse of America, i.e. the West.

Which got me thinking about The American West at the Toledo Museum of Art. Those long treks across the enormous expanse of the American West in the 19th century, accompanying expeditions or themselves expeditions, by the likes of William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton Watkins et. al. – weren’t they the first American photographic road trips, when there were barely roads (often Indian dirt paths)? When Ansel Easton Adams notices the light dying and the moon rising over Hernandez, New Mexico and stops to hurry with his plate camera to get the shot before it’s gone, how different is it from Joel Meyerowitz or Bernard Plossu grabbing a perceived moment from a car window in New Mexico? Is it the equipment which differentiates the photographs, large and slow vs. small and fast? Or is it, more importantly, cars. The American Road Trip is more accurately the American car trip in the minds of its curators, intimately connected to the freedom of choice, the directional control, the speed, the romance of the automobile – the car as camera. In a promotional video made for the book, Meyerowitz at one point actually says his car often felt like a camera with him inside, its windshield the viewing lens.

It’s tempting to talk about the book of The Open Road, which contains work by nearly twice as many photographers as the exhibition, but it is only the exhibition one encounters at DIA, or most of it. For reasons of space restrictions, 28 of the photographs in the traveling Aperture exhibition of 100 framed photographs are not included in the presentation in Detroit. Meanwhile there are three photographs included in the Detroit presentation which are not part of the Aperture traveling exhibition, instead drawn from the DIA’s own photography collection and added to the show (two Robert Franks and one Steven Shore). I find the ideas of a) space limitations necessitating removal of pictures from the Aperture exhibition and b) adding photographs from a particular venue’s own stores, somewhat at odds. Adding to the confusion, on reaching the last room of the truncated/augmented DIA version of The Open Road, I could step into yet one more room, which was empty of any art on its walls, photographic or otherwise. I’m told that room is often used for staging events in other parts of the museum. Seemed a pity.

None of these concerns should deter you from trying to see The Open Road at DIA. Even at just 75 pieces, the breadth of work on display by some of the most accomplished practitioners of the medium is exceptional. Each photographer’s work is handled differently in terms of framing methods, sizes and colors, unlike some packaged touring exhibitions and even one-off group photography exhibitions (the bulk of the recent After the Moment at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Art Center comes to mind). These mini solo exhibitions progress chronologically, allowing an apprehension of changing approaches and purposes of photographing, while also perceiving the continuing influence of early masters like Frank. Honestly, it’s a wonderful exhibition, filled with wonderful photographs by wonderful photographers. Inspect a wall-sized Joel Sternfeld color tableau for its punctum punchline (I won’t give it away, but it may be difficult to find in book-sized reproduction). Nearby, scratch your head at the unlikely, then understood as impossible, road scenes by Onorato and Krebs (included in their recent exhibition at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center), the inheritors of the mantle of the funky Fischli and Weiss, also from Zurich (and the birth city of Dadaism). Travel with Stephen Shore as he notes the streets and buildings he encounters, as well as the meals he orders. Count gas stations with Ed Ruscha in the early ’60s. Witness the formative years of semiotics in Britain with Victor Bugin’s image/text pieces, and the emerging primacy of color in photography in the U.S. with William Eggleston. Examine the selected examples by Lee Friedlander, reigning master of the road photograph and a living genius of the medium. This is like a photography history lesson of the last half-century.

And there are younger photographers continuing these traditions. Like Ohio born Todd Hido, who now lives in San Francisco and whose work focuses on what might be called America’s domestic underbelly, including the architectural desolation of suburbia at night and portraits of prostitutes in denuded hotel rooms. Or Alec Soth from Minneapolis, who is not only a fine photographer, concentrating on what The Guardian calls “off-beat, hauntingly banal images of modern America” in large scale projects often based in the mid-West, but also, through his Little Brown Mushroom publishing company, through books, magazine and newspaper format projects, publishes his own work and that of like minded photographers (including Todd Hido). Then there’s Justine Kurland, a Yale grad (America’s high diving board for success in the photo art world) who photographed utopian communities in rural Virginia and California and Ryan McGinley, a darling of the NYC photo set, famous for his pre-planned photographic road trips across the country photographing kids (his snapshotty book The Kids are Alright was published in 1999 while still a student at Parsons School of Design which led directly to his being one of the youngest artists to ever have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, at age 25). In 2014 a GQ article declared McGinley “the most important photographer in America” – so how could you leave him out. (Several of these photographers are known for their subjects often being naked). And there is generally what might be termed a casual, almost anti-aesthetic, catalogue-like imagery favored in the sometimes atypical examples of work by many of the photographers selected.

But having viewed this broad range of images, I am still pondering whether the exhibition achieves its stated goal of demonstrating/establishing itself as “the first consideration of the photographic road trip as an important genre.” Perhaps a sociological genre, a travel genre, even a vacation genre; but for me it doesn’t settle down into a definable photographic genre. In fact, in isolating then exploring this relatively narrow genre, the exhibition simultaneously explodes it, its point seeming to be to demonstrate how broadly encompassing the genre is, as though biting off more than can be digested. In an interview with Leica, Campany appears to confess similar doubt. “I was interested in showing the range. The genre – if road trip photography really is a genre [my italics] – includes everything from visual poetry and joy rides, to self-discoveries and political polemics. There are no rules.” His description is accurate, and indeed it’s all a pleasure to behold. I just don’t find the premise established.

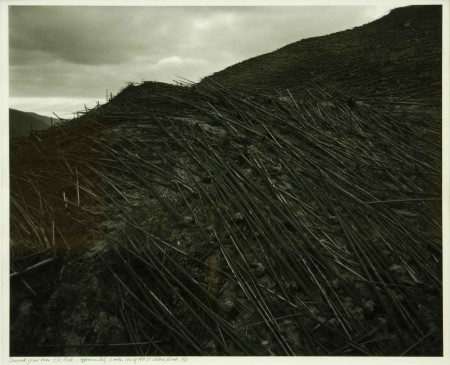

Frank Golke, Downed Forest Near Elk Rock – approximately 10 miles NW of Mt. St. Helens, WA, 1981 (from The American West)

No such ambitious goal was set by The American West: Photographs of a New Frontier, although what was believed achieved as emerging from the exhibition was “a portrait of one of the world’s great muses: the landscape of the Western United States.” The exhibition draws from the Toledo Museum of Art’s rich holdings of 19th century western landscape photography and purports to extend this portrait to the present (“the tradition continues to this day, with work by…”). Unfortunately, the purchasing by the museum of related photography does not appear to have extended beyond the 1980s with Frank Gohlke’s two post-apocalyptic, post-eruption Mount St. Helens records and Mark Klett’s camping scenes, both gelatin silver prints (black and white) and Richard Misrach’s human-affected landscapes and Type-C (color) prints – all view-camera images (Misrach was unfortunately named “Richard Miscarry” on one of the wall labels). Nevertheless there is considerable overlapping chronology and hence the possibility of image or even artist overlap between the two exhibition, yet none occurs.

Richard Misrach, Outdoor Dining, Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, 1992 from the series “Desert Cantos XV: The Salt Flats” (from The American West)

The Toledo exhibition is more rooted in expedition than road trip (appropriately, while most American cars were manufactured in Detroit, Jeeps were made in Toledo). More than 30 of the prints in The American West come from a single major gift in 1987 by a Wm. B. Becker – and more than half of these are albumen prints made in the 1880s attributed to Frank Jay Haynes, official photographer for the Northern Pacific Railroad and unofficial photographer of Yellowstone National Park (his Haynes Guide – Yellowstone National Park was published annually until 1966). There’s also work by George Fiske, who’d assisted Carelton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge and whose work inspired Ansel Adams, seven beautiful prints attributed to Watkins himself and three stunners by William Henry Jackson, whose Yellowstone photographs provoked President U.S. Grant to establish the first national park in 1872. There’s an exquisite 1873 Timothy O’Sullivan albumen print of Canyon de Chelly in Arizona’s Grand Canyon and two powerful portraits of Native American warriors made 35 years later, when they no longer had wars or lands. Made 30 years after these, in 1937, are two Edward Weston prints included (and flipping the date, there also is one by his son Brett Weston from Alaska in 1973), presaging six exquisite Ansel Adams prints in the exhibition. There also were numerous photographs by unknown photographers.

I found it interesting to note that so many of the early photographers of the American West came not from nearby mid-Western states but East Coast states like New Hampshire and New York (an exception was Haynes, from Michigan). And there was only one non-American (U.S.) photographer I noticed, Mexico’s great Manuel Alvarez Bravo, represented by four prints (which also may have been the only photographs not made in the U.S., expanding the expected definition of “The American West”).

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Canyon de Chelly (Walls of the Grand Canyon about 1200 feet in Height), Arizona, 1873

The descendants of much of the early work in The American West exhibition is what would be called after the late 1970s “New Topographic Photography” (from the title of an exhibition curated by Bill Jenkins at the George Eastman House), and existed coincident to much of the road photography on view in Detroit but is a separate genre. Yet the impulse, to travel the back roads or no roads, seeing what there is to see, going where you’ve not been before, making photographs all the while, is pretty much consistent with much of The Open Road. In the spirit of the early exploration photographers, Ansel Easton Adams travelled the American West on a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1948. By 1955, when Robert Frank won his Guggenheim to travel around the US, making what would become his seminal work The Americans, the road photograph would begin to supplant studied landscapes and portraits Adams produced, just as the hand-held 35mm camera would generally supplant the large format view camera of the sort Adams used. Yet appreciate this accompanying text to Adams’ perhaps most famous photograph, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico: “We were sailing along the highway not far from Espanola when I glanced to the left and saw an extraordinary situation—an inevitable photograph! I almost ditched the car and rushed to set up my 8 x 10 camera.” The aesthetics are different; the impulse the same.

This would be an ideal point to end this article about the two exhibitions, and does pretty well cover what I saw. But then I read on-line a description of the DIA show and learned some about what was absent at DIA. “The exhibition includes approximately one hundred framed photographs in various sizes, a slide show of “America Pictures” by Jacob Holdt, and items to be displayed in a vitrine.” If you were privileged to see Kevin Moore’s Starburst: Color Photography in America 1970-1980 exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 2010, you viewed a recreation of Helen Levitt’s 1974 color slide projection at the Museum of Modern Art of work she began making in 1971. The exhibition was meant to survey the best of color photography which overtook the US in the decade of the 1970s. Levitt was a good starting point, bringing an earlier street photography sensibility and largely domestic presentational device to color photography. I felt at the time (and still do) the exhibition missed out on the perfect end cap for the decade in Nan Goldin’s evolving, massive, multi-media slideshow “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” begun in the late ’70s.

Goldin’s work was a drastic departure from Levitt’s and really all other photographic work of the 1970s and would change the medium itself moving into the 1980s and beyond, establishing its own honest-over-good, raw, snapshot anti-aesthetic that would come to shape the fine art aesthetic. Yet radical and influential as Golden’s work was, it somehow pales before the slideshows Danish photographer Jacob Holdt was presenting around America. Arriving in the US in the early 1970s with just $40 in his pocket, Holdt stayed on five years, hitchhiking over 100,000 miles, crisscrossing America, crashing at over 400 homes from the poorest West Virginia black sharecropping family subsisting eating river clay for its minerals, to (the very next day) being picked up by the wife of Governor John D. (Jay) Rockefeller and staying in their mansion. As with Golden, a book was published, Amerikanska Bilder (American Pictures), in 1977, but was rather soon suppressed worldwide except in Scandinavia (eventually, 1993, Holdt published a facsimile in English through his own American Pictures Foundation; it’s now out-of-print but I found used copies on-line for as little as $5.65). The work is the most revealing, exceptional look at American life and its extreme social inequities, as though pulling up a continent sized rock to photograph the teeming life beneath it. I’ve met Holdt several times in several parts of the world and each time watched his evolving 6-700 slide presentation; it is one of the most powerful experiences I have ever had in photography by one of the most exceptional humans I have ever met. American Pictures is the photographic road trip to end all road trips, and its absence from the exhibition at DIA was profound and disappointing.

The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip continues at the Detroit Institute of Arts through September 11 before traveling on to museums in Texas and Florida. Also, this fall, as part of the FotoFocus Biennial, the Cincinnati Art Museum at The Mercantile Library, the Taft Museum of Art and the Weston Art Gallery all will be exhibiting photographs of or inspired by the American West.

– William Messer

William Messer is a photographer, critic, curator, educator and environmental activist. He has written for dozens of publications in as many countries and is an elected member of l”Association International de Critics d’Art (AICA), founding of its Commission on Censorship and Freedom of Expression. In Cincinnati he regularly curates exhibitions at Iris BookCafe and Gallery and leads its Second Sunday Open Critiques, and recently co-curated the After the Moment exhibit at the Contemporary Arts Center for the 25 anniversary of its prosecution for presenting the retrospective exhibition The Perfect Moment by photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.