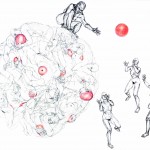

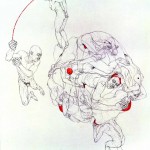

We met Sol Kjok in the early 1990s when she was a grad student at UC, in fine arts, though she already had an advanced degree in European literature: her art, then, focused on the metaphor of the circus, life lived on a flying trapeze, lived swinging in and through the air; her figures often referred, too, to the Harlequin, an early European trope close to the court jester, an idea also reinterpreted in early Picasso, in his Blue Period. Sol Kjok’s interrelated, interdisciplinary ideas were very rare in the 90s, when literature, in particular, was rarely read or rarely integrated into the visual arts. Although collage-like, most of Kjok’s figures were integrated single paintings, and she frequently utilized reds, blues, and yellows, those primary colors of twentieth century modernism, to indicate the universality of her themes and her figures. These early pieces of Kjok’s , however, set her themes for her career, a most distinguished one in New York, lately moving into Europe and probably China. She recently and almost accidentally discovered the work of Max-Jakobosen; both of them work with universalist themes, with the nude figure predominating: both are interested in visualizing The Dance of Life, perhaps another version of The Tree of Life, which manifests itself in nearly every great religious/spiritual tradition in both East and West. Their idea of interconnectivity has recently shown up in the Western biological sciences, as well, so that what they’ve intuited is turning out to be , if you will , “real”, in science and in the arts: both artists had already intuited what science is now beginning to prove, about the interconnectedness of things, a concept more Eastern than Western, but The West may be beginning to catch up. Both artists are working under the banner headline (show titles) of “In the Air”, recently exhibited in New York City, where Sol lives and works, and which we hope is heading to Europe and China.

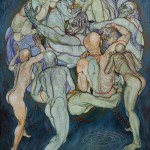

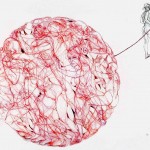

Kjok works with nude figures, always bald (so that hair isn’t in the way of her deeper concepts); the figures generally twine together and, rendered as a whole, represent the universe itself, a kind of latter day Sistine Ceiling, though there’s no central image, say, of God giving life to man (Adam, in Hebrew, means man). Buddhism has always believed in the interconnectedness of all life, and Kjok and Max-Jakobsen both prefer to work with human life, so that each one of their works is a kind of universe unto itself; both of their

work exudes a kind of high energy (the word energy is used in the Eastern sense) interconnectedness. No one figure dominates; the combined figures often seem the shape of an orb, which is a visual concept with which Kjok has long been fascinated (is it a moon? sun? both?). I’ve often wondered if these bodies wrapped into one another aren’t a version of the setheraph of Kabbalistic Judaism, which might then morph into the Gnostic Christian tradition as well: we feel as if we are in the presence of angels, as if the energy of

and from many bodies in an unbroken orb are the very stuff of creation itself, and Kjok equates creation with the greatest act of love in the universe: her love of these figures/bodies, and her wavering, strong curvilinear figures seem in the very act of being created, before the vessels in the Kabbalah have broken: hers is the universe still perfected, before any fall, so these orb/figures represent the highest form of hope, almost as if God is in the very act of creating those most like Him, human beings. Kjok’s figures are not specifically religious, and don’t represent just one religious tradition; like many artists working since the ’60s, she’s searching for a larger spiritual presence, and her drawings, paired with those of Max-Jakobsen, are right midway between the perfected figure of the Renaissance and the more attenuated figures of Expressionism: she proposes a radical likeness between these two traditions of Western art, suggesting a holistic joining of two traditions , usually separated into the binary “harmony” and “distortion” in Western art and philosophy. And her male and female figures may be defined, partly, by their genitals, often highlighted in red, but that’s more to suggest the infinite possibilities of rebirth, re-creation, which her figurative works always suggest: it’s the possibility of endless regeneration, which brings her art into the Indian/Buddhist/Hindu traditions, which Kjok proposes. This is very smart stuff, heady and transcendent. “In The Air” was exhibited in New York from June 2 to July 2, and we hope that the exhibition, or one like it, will indeed go onto Copenhagen and to China.

If you’re unfamiliar with Sol Kjok’s work , we urge you to look it up on the internet, as you’re not likely to see work like hers anywhere, and her new partnership with Max-Jakobsen, makes her work and his work more than doubly strong: their connection is more geometric and leads towards a kind of implied infinity, which is where Kjok’s figures may well reside in real time. She combines the best of Classicism with the best of Romanticism, and she draws like an angel. If we could make Egon Schiele’s drawings the opposite of solipsistic, and reverse their introspection, we might have him meet Sol Kjok midway to the heavens and to the Universal Spirit.

–Daniel Brown