“[‘The City’] can be any city in America. These individuals can be any American. There is a false sense that these threats ever were (or still are) contained at the peripheries of society, in small towns, backwoods in uneducated and poor communities.”

— Vincent Valdez (b. 1977)

Last month, a group of about 20 gun-toting members of a “White Lives Matter” group gathered outside of the Houston NAACP office in the third ward—Houston’s historically black neighborhood—to protest the NAACP’s failure to denounce the Black Lives Matter movement. As usually happens with licensed displays of bigoted freedom of speech, counter-protesters outnumbered the confederate-flag waving street campers. A multi-ethnic group joined hands in a prayer circle across the street. Twitter users reliably tweeted ridicule. Far more of us chose to ignore their petulance and avoided that city block as we passed through to buy groceries in another neighborhood. I revisit this scene not because it’s particularly common in Houston, but because everyone dealt with it in a different way. What are the ways we delineate evil?

For Vincent Valdez, evil is overwhelming, bombastic yet unassuming, and jarringly familiar. “The Beginning is Near (Part I)” is the San Antonio native’s first solo gallery show in a decade, and it makes a decisive blow. Despite its relevance in our current political climate, Valdez has been working on the concept and execution of “The City I” since 2011.

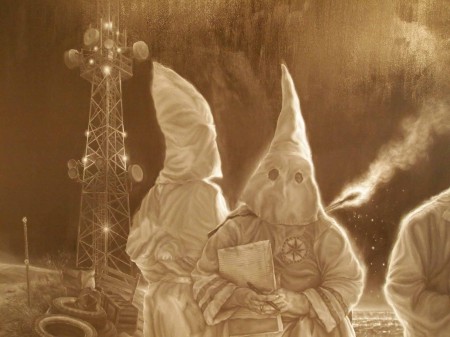

Both the banality and eerie omnipresence of evil envelops the viewer in the exhibition’s two oil paintings, on display at David Shelton Gallery through October 8. “The City I”—more than six feet tall and 30 feet long—turns the viewer into an unwilling participant at a Ku Klux Klan gathering. Fourteen Klansmen and -women—one of whom is a baby in his mother’s arms—and one dog organize, gossip, drink and play on iPhones as the city lights sparkle beyond. It’s possible that the number of hooded figures mirrors the white power edict “14 words”—a slogan prominently displayed on the white protesters signs in Houston—which professes the need to protect the future of the white race.

You’d be hard pressed to find a person that the Klan doesn’t illicit an immediate reaction from, and the sheer size of the painting makes that uneasiness unavoidable. Is this why two middle-aged couples quickly wandered in and out while I was at the gallery on a quiet Saturday afternoon?

“Some say the Klan today should just be ignored. Frankly, I’d like to do that. I’m tired of wasting my time on the KKK…. But history won’t let me ignore current events. Those who would do violence to deny others their rights can’t be ignored.”

— Julian Bond (1940-2015), historian and civil rights worker

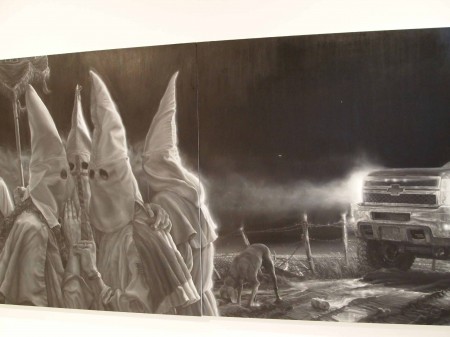

Gallery owner/namesake David Shelton was also present for my visit, and when I asked him about using photos from a press kit, he told me there were none available, indicating a large tabloid program as their main photo vehicle. There’s been plenty of press, most notably in the New York Times last March while Valdez was still painting it—but most stories and announcements in Houston use the other painting in the exhibition, “The City II,” as the primary press photo: a 70 by 90-inch black and white oil painting that seems to be just out of frame from the larger piece, depicting a pile of old mattresses and assorted trash.

From my conversation with David, it became clear that the centerpiece’s unwieldy size was not the only reason it wasn’t widely circulated: the Klan is an incendiary topic (pun intended), and context is vital. That’s what the tabloid program provides: a short retrospective of depictions of the KKK in American art written by Andrea Lepage, an interview between her and the artist, and a centerfold image that manages to do some kind of justice to the behemoth “The City I.” David didn’t say this explicitly, but I have to believe they didn’t want Valdez’s opening to involve fending off armed “protesters” defending their brothers in white whom they’d seen maligned in a press release.

But, those who would want to defend the Klan are few compared to left-leaning Houstonians who may glance at press release full of white hoods and perhaps label it as lazy and reactionary, moralizing, or glorifying a heinous boil on American culture. In our enlightened society, shouldn’t we move away from the KKK’s shameful history?

In this case: no. First of all, anyone who says we’re “post-racial” is fooling themselves, and anyone who would accuse Valdez of being “lazy” hasn’t been engulfed by this masterful, almost photo-realistic work. Lepage’s retrospective of American art depicting the KKK reminds of us this important tradition in highlighting the failure of America’s democratic promise, and in her interview with Valdez, he specifically mentions Philip Guston’s 1969 painting “City Limits,” which depicts three white-hooded figures cruising around the city in a car. As I mentioned, this particular piece has been in his head since 2011, inspired by Guston’s work and poet/performer/activist Gil Scott-Heron’s (1949-2011) song “The Klan,” which was released in 1980.

The painting’s black and white color scheme implies a time gone by (not just a harmful binary), which makes the presence of a smartphone, toy Pikachu and J.C. Penney charm bracelets all the more jarring. The size of the painting is what makes it especially remarkable—you simply cannot see the figures as faceless devils. This painting blows up their eyes, their humanity, normalizing evil with the gleaming city in the pack’s crosshairs.

I thought of Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch,” admittedly because of the size of “The City I” at first, but the “watch” aspect the Klan keeps over the city is incredibly chilling. And the Klan has always been militarized, however disorderly. Only one figure here appears to be armed, and funnily enough, his is the only face not obscured by a white hood, though it is half-obscured by another hooded man. His glare is one of the most chilling of the fourteen figures.

Speaking of, let’s meet the gang:

- The gossips. My friend was immediately drawn to these two figures, on the far right of the painting. To her, they conjure images of the Last Supper, and she noted that, if you don’t count the baby, there is the same number of people at the “table.” Then, we are given the unpleasant task of figuring out which klansman and -woman corresponds to each disciple, and the son of man Himself—just another provocative layer to “The City II.”

- The baby. I’d seen photos of kids in Klan costume, but never as young as a one-year-old. He writhes in his mother’s arms, pointing eerily at the viewer. In his other hand, a stuffed Pikachu dangles from his grip. Not a creepy doll-head or otherworldly devil toy—a Pokemon, which a surprisingly huge percentage of us have been chasing on our mobile devices all summer. Is he accusing of us allowing him to be raised racist? Or is it more of an Uncle Sam “I want you” gesture?

- The iPhone pecker. KKK members need the same dopamine hit as the rest of us from their glowing screens. And how else would he effectively troll black celebrities on Twitter? Or, is he disillusioned with his surroundings, seeking other connections and realities?

- The bureaucrat. He holds a rough-looking legal pad. Perhaps he’s taking attendance? Even an agenda of evil is still an agenda.

- The “Heil America.” Sure, this guy could be waving, but in this painting, it’s almost definitely a Nazi nod. He’s also gripping the Budweiser can, but remember how they temporarily rebranded themselves “America”? Thanks for making symbolism easy, Budweiser.

Budweiser must have known this would happen when they changed the label of their best-selling swill. It will remain until election day in November, when we will elect a new president and trash cans will, presumably, overflow with crumpled “America” remains. I will absolutely not make a classist crack about how white supremacists are probably some of the most reliable consumers of Budweiser, and that Budweiser is well aware of the fact that faux freedom fighters of the conservative side are ready to gobble up this false image of America. What I will say is that I hope future art historians are aware of the marketing ploy and don’t read the “America” label as heavy-handed commentary.

- The very ordinary hunting dog. He reminded me immediately of W.H. Auden’s poem “Musée des Beaux Arts,” which remarks upon Pieter Bruegal’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” in which Icarus is only a tiny pair of white legs crashing into the sea among the much more prominent medieval landscape. Life continues in the face of tragedy, where, Auden writes, “the dogs go on with their doggy life.” The Klan’s dog does not wear a special dog-hood, but does smush his face into the dirt, going on with his doggy life in the glare of the pick-up truck’s headlights. He’s bird dogged to find something in that dirt, like the KKK is bird dogged to maintain white supremacy.

In short, the painting is definitely worth the press, not least of all because it’s Vincent Valdez’s first solo show in ten years. David Shelton Gallery has done a stellar job, particularly with the accompanying tabloid program. Read the whole thing while standing in the presence of this intrusive, black-and-white ghost of a potential future and hidden present.

“For underneath his white disguise

I have looked into his eyes

And I say brother, brother, stand by me

It’s not so easy to be free.”

—Lyrics from “The Klan” by Gil Scott-Heron

(All pull-quotes are from the program for “The Beginning is Near (Part I),” published by David Shelton Gallery, 2016.)