Emerson’s idea of how to see Nature was to look up; Thoreau’s idea of how to see Nature was to look down. It drove Emerson crazy. Instead of becoming a great Transcendalist thinker, Thoreau, to Emerson’s mind, went huckleberrying. While Emerson sought to capture the Universal Soul in Nature, Thoreau bent over and watched red ants and black ants battling it out.

Joshua White—a 2008 BFA graduate of NKU–keeps the sensibility of Thoreau alive. Nature for him is an ongoing treasure hunt; he is interested in what can be found. “My mother,” he writes, “tells me I used to lie on my stomach and watch ants crawling through the grass for hours. I remember catching June bugs off of her wild roses in a Styrofoam cup.” White has looked hard, in his actual yard in North Carolina and in yards and spaces far beyond, to find and photograph with his iPhone many gallery walls worth of specimens. Some of the specimens are massive and some are delicately linear; some are museum quality, perfect in every way, and others are mere fragments, things that have fallen, or been torn, apart. Some have the elegance and symmetry of medieval ironwork and some make you itchy just to look at them. White is an empiricist, and takes what he can get. Sepia-toned photographs of all of them—of weeds, flowers, seeds, mushrooms, crawling creatures with six legs or eight legs, and some with many more, plus birds, reptiles, and even the occasional mammal–are mounted in orderly rows around the perimeter of NKU’s large gallery space. At first glance, the pictures read like the illustrated addendum to a 19th century plant physiology textbook. The images are titled with their Latin names—there is a taxonomist’s energy to White’s work—and a number—he has done many hundreds of these pictures—and (first and foremost) their street names. I did not know until I saw this show that there was a flowering plant called Love-in-a-Mist, or that one of the more common of the woodland toads I might have seen was named after the 19th century naturalist Samuel Page Fowler. We’ve labored, for centuries now, to name them, often in honor of humans’ first experiences with them.

Part of what makes White’s vision so powerful is that he has not hierarchicalized his walls of specimens. He pursues his subject matter with the uncritical curiosity of a child with her first microscope. Virtually everything is interesting. White has photographed the dense and rough textures of Nature’s protective surfaces on the wings of a moth or Carolina Allspice. He has captured the way Nature supports itself, the visible systems that enable things to live. These plants have veining of all sorts, febrile linear webs that do, well, whatever it is that they do for a Jimson Weed Pod, or a Winter Aconite. The smaller the creature, the more likely it is to be segmented, like his American Giant Millipede or the Garden Snail Shell. This is the romance of functionalism. (What’s in it for Nature to make so many things segmented? And how come we’re not?) Some of the images, like Chestnut, are plainly sexy (after all, reproductive organs are reproductive organs), and White’s Blackberry is as lush and fruitful as Diana of Ephesus. White has captured the way that Nature works as a limitlessly energetic life machine.

But Nature is also clearly a death factory. In spite of the way we can celebrate how efficiently each species has been designed, the show records individual specimens whose backup systems have failed. White came back to town for the opening and gave a talk that I unfortunately missed. I would have liked to hear more about his methods and operating procedures, but it feels safe to say that the show feels like a salvage operation. Everything in the show is a memorial to something whose time has passed (he does not do, for instance, rocks). It’s a little like visiting a gallery of ancient Roman portrait heads.

From one perspective, this is the final stage of functionalism. Fruitful to the very end, when Nature has completed its job, the specimens are now ready to become interesting to White. Nature does not seem to be Nature for him until it is morte. In the history of western culture’s Nature illustration, there has been an ongoing conflict between the infidelity of trying to capture a specimen while it’s still alive and the infidelity of trying to capture a specimen when it’s dead. (This is the story of Audubon, for example, our great, reanimating, zombie artist.) Death can be a great transformer. White’s Lightning Bug looks very little like our experience with them on a June evening, for example; it stands upright, a bit like a cartoon penguin with extra limbs. Death haunts the living. When I saw White’s freshly unreeling Christmas Fern Fiddlehead, I couldn’t help wondering how long it might last. The photographs capture life stalked by decay and already bearing its marks. The petals of the beautiful but haunting Rose Cultivar are browning and spotted. The Black-eyed Susan is folding up shop. The Daisy, seen in profile, looks like it has been flash-dried. In its sepia portrait, it could be carved out of stone, or like a 19th century archeologist’s photograph of some well-preserved ancient offering, the detritus found on the floor of the inner chamber of a Pharaoh’s tomb.

The images are dead but far from lifeless. (Sometimes they struck me as the sort of Nature pictures Atget might have taken.) By and large, they are less sculptural than, say, the Gothic modernism of Karl Blossfeldt (with occasional striking exceptions, such as White’s Buttonbush Flower), and display White’s eye for drama, sometimes lyric and sometimes forensic. The Robin’s Egg shows the violence required by the chick to get out. The Sphinx Moth hovers (in profile, no less—I’m curious how White mounted some of his specimens to photograph them—we never see pins or other signs of support), its legs dangling, partly ready to absorb the shock of landing and partly blowing in a wind and partly, perhaps, on independent quests of their own, one of several species who end up looking a bit like one of H. G. Wells’s aliens. There is a taxidermic feel to several of the photographs. The Ruby Throated Hummingbird is well into its decay and starting to lose its shape; if you want to keep your looks after death, there is a real advantage to having an exoskeleton. The Japanese Maple Leaf Buds seem to be caught up in a fairly stiff breeze, though of course we know they’re not—not any longer.

Nature photography, like any other genre, reflects its age. Anna Adkins’s cyanotypes capture the evanescence of an image and the usefulness of the outline to identify species for the gardener. The wonderful photographer Charles Jones captures the earthiness of the late Victorian imagination with photos of fruits and vegetables that are as individualized as characters in a novel and as frankly sensual as anything in D. H. Lawrence. Blossfeldt’s twigs look like a project undertaken by the Bauhaus to capture the delight of natural mathematics. In White’s work, there is a whiff of the postmodern, with its appropriation of a much older look and its faux-encyclopedic inclusiveness. White approaches the huge variety of nature with the appreciative eye of the taxonomist, the filer, the categorizer interested in systems. Its richness is a little more like the richness of some fabulous book than the richness of an actual backyard.

There is something a little regimented in the repetitiveness of the images: each photograph is 4 by 4 in a 10 by 10 frame; each actual image is probably no larger than an inch or an inch and a half large. And there are 200 of them, which probably doesn’t invite most viewers to spend a great deal of time on each one. Surely certain portions of the show must just wash over their audience, perhaps as the specimens would if they were still alive and encountered au naturel. I think we are meant to be a little overwhelmed, though never lost. White has explained that he has thought that an alternative to a conventional gallery hanging of his pictures would be to do an installation, simulating the kinds of places in nature where he secured his specimens. But from a different perspective, the exhibition as it stands is already something of an installation piece.

From time to time, White’s interest in his material seems almost clinical. He has surgically altered some of the specimens, cutting them open to reveal them—typically, their multitudes of seeds–in cross section, and complicating our sense of just what is inner and what is outer in a thing’s natural appearance. A few of the images are as compactly designed as if they were the logos for some unknown commercial product (like the Rouge Cardinal Clematis Bud). I would say that the images as a whole are emotionally restrained—not too elegiac, not too ecstatic. They are elegant—sometimes as curvilinear as 1920s interior design drawings (like Spider Flower)—and never boring.

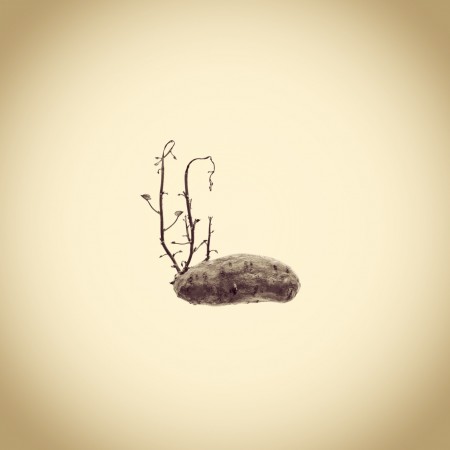

A few really stood out to me. I was struck by the Mating Crane Flies. As if caught in amber while reproducing, they satisfy our sense that eros and thanatos have a certain rendezvous that cannot be denied. It is hard not to see this image of eternal coitus with a certain prurient satisfaction, but also with a bit of survivor’s glee. The Robin’s Egg is an unusually powerful picture. It looks like material evidence to some ancient murder, or an example of Bronze Age trepanning. It manages to capture both all that is fragile in an egg and yet give off the sense that it has been carved out of stone. The picture of a dried Rhododendron Flower looks like it is being whipped in the wind, its lifeless leaves trailing behind it like Isadora’s scarves. My favorite single picture might have been Sprouting Sweet Potato. Shoots emerge from its large, curved back like spouts of air from some Leviathan. They seem to be starting Tim Burton-like forests of their own on some floating island like the type you see in New Yorker cartoons. The picture suggests the dispirited fruitfulness of worlds within worlds, a specimen that is engaged in both renewal and death.

If I had been at White’s gallery talk, I might have asked him about his ideas about scale. It is easy to imagine how some of these images would look like blown up several times their current size, but here, everything is the same. (This may be because of the resolution limits even with the best iPhone camera, but that too, of course, is a choice. The iPhone camera is notoriously excellent for on-the-go sorts of work; it is far more rarely used as a studio camera, and it’s not clear what its advantages are for that sort of thing.) It is unsettling to experience a world where larger things, like a luna moth or a paper wasp’s nest or a box turtle, are reduced to the same size as an American dog tick or milk weed seeds. Honey, I shrunk the squirrel. The smallest things have become monumental, and the larger and heavier things, like Bottle Gourd, seem to be floating. It is an interesting trade-off. White has taken weight and mass out of the equation. In their place, we have as much line and surface as we could possibly ask for. Perhaps this is what always happens with book illustrations, it’s just that we’ve gotten used to it. All the myriad things from all those backyards have been willfully transformed and contained in ten by ten cases. It’s as if they have had a spell cast on them. In the end, one of the effects of the show as a whole is that you are witnessing a kind of magic. There’s something Harry Potterish about all these ten by ten oak frames that together hold the amazing forms of all the natural stuff you can see in the world by looking down, one thing at a time.