Zephyr Gallery has a twenty year history in Louisville, moving from location to location as the community needs and sees fit. Project 17: Ritual Geography is part of an ongoing project started in 2014 by Zephyr. Their ongoing Project series is made up of curated proposal-based exhibitions as well as collaborations with universities, colleges, and cultural institutions. Project 17: Ritual Geography is the seventeenth in this series. The exhibition’s intent is to discuss how humans have shaped geography: in particular, how women have contributed to that shaping. All contributing artists are women; Joyce Ogden, Sarah McCarrtt-Jackson, Adrienne Miller, and Mary Carothers. All of these artists are influenced by land and sea— and use those materials to evoke how we have constructed and perceive both interior and exterior space.

Ritual Geography was curated by Eileen Yanoviak, a PhD Candidate in Art History at the University of Louisville, a contributor to Burnaway: The Voice for Art in the South, and has worked in museums including the Arkansas Arts Center, Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft, and the Speed Art Museum for the past fifteen years in a variety of capacities from curatorial to education and development.

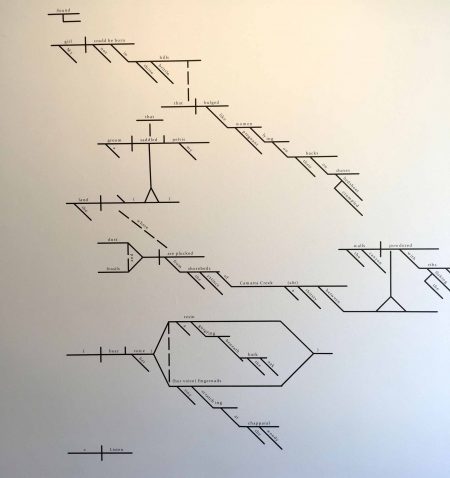

Sarah McCartt-Jackson had three different poems shown within this exhibition: Animals, Halocline, and Sound, all from the series Rinconada (2017). In this exhibition, her visualized poems become vinyl linguistic maps. I’ve been a fan of her work for some time (if you’re a fan of naturalist poetry and haven’t read Children Born on the Wrong Side of the River, put it on your to-do list). For the sake of speed I’ll only dive into one poem: Sound (2017). Sarah’s recent visualized poems focus on the “unheard voices of women who experience abuse by creating a landscape of psychological spaces”. The opening line “My girl could not be born in those brittle hills” is full of the dividing feelings of love and disdain that one can feel for a place she wishes to leave—or perhaps I’m projecting a bit. When the author/artist places location and language next to each other, she reminds us that these two ideas are equals, and can be representative of the same thing. After all, places are similar to people in that they have the ability to stay the same or become new with time. Language is such a huge indicator of place— dialect can pin down your location with tremendous accuracy— and it morphs with your change of place.

I found it really interesting that McCartt-Jackson was directly influenced, in part, by Adrienne Miller’s use of “angles and texture, as well as Miller’s focus on the capacity of landscape and abstract spaces to express human emotion”. Parallels exist in the ways that both artists create an idea of negative space for the viewers to project their own ideas and experiences onto— a fulfilling way to experience the work.

Adrienne Miller. maintaining the overgrowth (2017). acrylic gauche and colored pencil on paper. photo courtesy of author

Adrienne Miller uses the most traditional of materials for this exhibition: acrylic gauche, colored pencil, pencil, and pen and ink on mylar. Her colors are minimal: soft greens, stone grays, neon yellow accents, and gray with a lot of negative space— which is beautiful,as it allows the mylar to be sleek, clean, and fluid. Miller constructs abstracted spaces to represent our intimate spaces: our homes, crannies of the spaces where we work, and other beloved spaces. These drawings are simple compared to the installations that surround them— but they allow the viewer breathing room and that’s so important. maintaining the overgrowth (2017) was the piece I was most attracted to: its connection with the wrangling of the outdoors connected well with the other pieces, but its geometric quality was also appealing— it reads like a curated memory of homes upon first visit— which I find interesting.

Joyce Ogden’s work in this exhibition has the most presence within the space— and I’m not certain if this was intentional, or if I just imagined it— but her work (which contained a lot of natural material) contributed to an earthy scent. In particular, Dilla (2016), which consisted of a large bundle of A. graveolens grouped together with hemp cord, gave the upstairs gallery a lovely floral fragrance. Ogden had several pieces in this exhibition, but I’m just going to discuss Gathering (2015-17). Gathering is one of Ogden’s smaller works for this space: an installation of twelve repurposed science lab flasks, beeswax, and steel. The flasks are arranged in groups of four: a year’s worth of collections, taken once a month from August of 2015 through July of 2016. Next to the installation is a list of materials found at various levels of decay in the flasks: cherry tomato, goldenrod, thistle, viburnum leaf, winterberry, snow, daffodil buds, redbud flowers, plant stem, comfrey flowers, honeysuckle vine, and dill crow. The collection is small and incredibly endearing. Ogden’s work “deals most directly with the very substance of the land”. Her work is filled with sentimentality for an agricultural way of life that continues to exit the day to day existence of most Americans. Her work also inherently discusses women’s traditional interaction with the land— one of collection and preservation.

Joyce Ogden. Gathering (2015-17). Repurposed science lab flasks, beeswax, and steel. Assorted natural material. photo courtesy of author.

Mary Carother’s installation A Place Between (2017) is the show stealer when considered through scale alone. The viewer walks up to Zephyr’s second floor and is surprised by the immense installation taking up two of the three room gallery space, as well as the attic. A Place Between consists of wood, rope, and sand: wood for the skeletal boat structure that rests among the attic beams, acting as a central anchor for the rope. The rope acts as a diagonal linear device connecting the viewer’s eye from the boat structure to the wall, where the rope “takes root” via tiny twists anchored by small paneling nails. The floor is partially covered with sand and additional rope, the knotted rope (the knots were made in collaboration with the Kentucky Refugee Ministry) peaking from under the sand. The viewer is immediately hit with visual references to the beach: the sand is poured heaviest along one wall and is spread thinner and thinner to the center of the room, leaving an uneven line that recalls the earth meeting and falling into the ocean.

A Place Between was made in response to Carothers’ own travels to the Outer Hebrides Islands to “trace a female ancestor who entered the United States undocumented during the Civil War”. Carothers’ made this work as an homage to immigrants and her own ancestral immigration story— linking our past, present, and our future. For me, the most successful aspect of this work was the presence of the ocean, without ever containing any water: from the line at the sand to the boat in the rafters, Carothers is able to bring to mind the tumultuous relationship that human civilization, and in particular immigrants, have had with the ocean for centuries. After all, the water does mean so much for us, right? Water can mean fear, life, death, aggression, hostility, love, perseverance, and hope.

–Megan Bickel