While I was in New York, during my second day in the city, I finished a studio visit with Angela Heisch, and headed to David & Schweitzer Contemporary to see Mary DeVincentis’ paintings in a group show called Fables of the Reconstruction. The title of the exhibition is taken from the R.E.M. album of the same name, which was originally to be titled The Sound and the Fury, as per the Hemmingway title which borrows famously from Macbeth.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

The exhibition featured paintings by Mary DeVincentis, Peter Burns, Lizbeth Mitty, and Helen O’Leary whose work negotiates a unified formal language between painting and sculpture. I’ll be focusing exclusively on DeVincentis’ work.

I met Devincentis’ at the opening of the exhibition that night and we discussed the possibility of arranging a studio visit later-on in my stay. As arrangements started piling up I wasn’t sure if it was going to work out or not. After some back and forth I finally made it to DeVincentis’ studio on my last full day in town. It was raining and I caught the train to Times Square and walked a few blocks to her studio.

DeVincentis’ works in both oils, generally for larger works executed on canvas, and in acrylic, generally smaller to midsize paintings executed on Yupo which is a translucent paper of various applications; sometimes the media are mixed for the sake of effect. The selection of works presented for this exhibition at David & Schweitzer was a healthily mixed bag of DeVincentis magic. There were two larger canvases and fourteen smaller paintings on Yupo. Two years ago, DeVincentis traded the printmaking process of monotype for the silky substrate that Yupo provides wherein the same painterly effect can be achieved without the facility of a printing press, which can be a cumbersome situation to attend unless one has the luxury of a printing press in the home. Monotype is a loose process of printmaking, often referred to as the painter’s print, an image is applied on plexi-glass with the diluted oil based ink most commonly -used in printmaking. The ink can be variously applied with brush, knife, brayer and may be reduced or added to with a stencil cut of mylar that may be inked itself to add color, or left clean in-order to mask. The possibilities of monotype are fair endless, and color layer after color layer may be applied. The sensuality of monotype is the transparency one can achieve, and in the extent to which mark can be varied and manipulated. Printmaking is also a process wherein variables often present complete and utter upset to the desired final product. Monotype, perhaps more than any other process of printmaking, is the place where these variables can be relied upon to deliver happy accidents and unforeseen results. This fluidity and also the confidence and acceptance radiates from DeVincentis’ paintings.

She works into narratives and around notions. The paintings for me emerge episodically in a non-linear fashion around ideas and systems of belief frequently concerning religion and cosmology. One of DeVincentis’ ongoing series is Sin Eaters. Historically Sin-Eaters were poor persons who were paid meager wages to eat bread and drink beer over the corpses of unconfessed souls who’d died suddenly and without the benefit of a priest by their bedside. The practice originated in The Marches, or the land surrounding either side of the border between England and Wales. Richard Munslow is reported to have been the last known Sin-Eater and was buried in Shropshire, England in 1906. The practice of Sin-Eating is unmistakably derogatory, and in-spite-of the practices’ salvivic thirst the behavior would surely guarantee your eternal damnation. Such is the nature of DeVincentis’ work. Human folly, visual poetry, fables, legends, memory, archetypes clad in nuances born of language and oral tradition. It is this sort of tragedy and human drama, camped in ego, and drunk with mystery, that makes DeVincentis’ work relevant to the thematic bent of the exhibition. For instance, one of the many paintings we looked at was of Jesus taking a nap in a fishing boat. The boat is grotesquely foreshortened and Jesus is sumptuous in last recline with dramatic green waves threatening to completely upend the laws of physics. Among the churning waves are a series of skulls meant to signify the disciples and all their unfaithfulness. I loved it. The skulls are truly a spiteful depiction of the disciples, and they bear a strong resemblance to wrathful Buddhist thangkas’ depictions of skulls. I feel like DeVincenti’s paintings uphold a message of optimism that casts the sometimes hard to take light of ego death on deserving characters, and invites swells of sympathy where the kind hearted or benevolent become the scapegoat.

Speaking with DeVincentis about her work it became extremely evident that for one she’s into stories, reading them, and sort of living in them, stories from all over the world, fiction and non- fiction and mixtures of the two, and writing them down with paint. She told me that she has never had the ability to visually recall memories or even the faces of people with whom she’s extremely familiar. She told me that the images have always had to come from words first. This smithing of picture words feels very joyful from the receiving end.

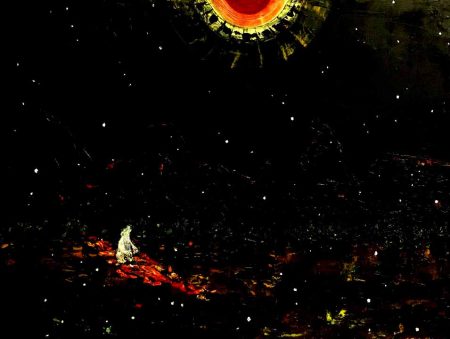

When I first saw the above painting it immediately reminded me of John Martin’s engravings for Paradise Lost, and Clement Hurd’s The Runaway Bunny. Devincentis’ work operates in a playful vernacular that offers dictums of goodness wearing romantic clothes of laughter. Romance is perhaps the quality I gather most from her work. Her cast of characters in Fables of the Reconstruction reminded me of a Fellini film. DeVincentis’ characters enact their dramatic truths with great pictorial gravity. I think that Desert Night is the perfect example of this. While we are presented with a screaming Tiger, arms outstretched in defiance of the void, the Tiger is at once both humorous, and terrifying.

DeVinenti’s work speaks to a greater continuum of our human mythology. Her painting is honest and direct much in the way that children are. Her quality of rendering is not bound by notions of the real or conventions of representation grounded in formula. The hard won favor of play is bleeding from each brush stroke, and in them the motion of life’s vitality is swimming. That time is short and happiness is enigmatic. The danger that DeVincentis pairs so poetically with human urgency, desire and joy is a humorous coupling and one that well expresses the great gamble of the human experiment, its smallness too.

–Jack Wood