A show about the nude can’t help but raise issues about voyeurism any more than it can help raise questions about sexual politics. (I counted, for example, only four representations of the male nude to nearly twenty female.) This is the Manifest Gallery’s ninth show featuring the naked body, and I would have liked to see this year’s version juxtaposed against the past eight to see what they add up to. But as voyeuristic experiences go, this is pretty placid. The show is mostly a collection of pictures of bodies at rest, which makes sense because that’s where the art world’s naked bodies are most frequently encountered: in the artist’s studio. Our relationship to them is that we find ourselves looking over the artist’s shoulder. These are pictures of naked people holding still in front of an artist for such long amounts of time that they require a fair amount of athletic skill. These are not bodies as encountered in the marketplace. Is any other genre so studio-bound?

The Manifest’s signage notes that “We use the human nude to master skill, understand ourselves, and push social and psychological buttons for the sake of expression (sensual, delicate, political).” And the skills that are mastered are considerable. James Grubola’s “The Friday Sessions Series: Sunburn Feet” (2016) shows a woman’s body at rest, rendered with consummate skill and a remarkably lively and sensuous line. The title suggests, perhaps playfully, that the drama of the drawing is to be found in her feet, though the purported sunburn is barely visible. Her thighs are drawn up (at rest and for modesty), but her hands are twisted in her hair in such a way as to suggest an inner tension complicating the sedate pose. Though the promise of “sunburn feet” in the title suggests that this is a body with some history, one that has had a previous encounter with the great outdoors, the truth is that the academic nude—the body represented by artists as a way to “master skill”–is pretty much a body without context.

By and large, the nudes at the Manifest are without narrative. They are generally expressionless. They are un-erotic, and sometimes counter-erotic. These nudes show little emotion—no laughter, no fear—and little acknowledgment that the models aren’t wearing clothes and you are. A few of the works are animated, such as Nick Reszetar’s diptych “Virum et Muliereum” (2017). There is something Michelangelo-esque about the ways that the full size figures are trying to emerge, to tear themselves away, in elegant, active swirls of paint, from their backgrounds. The male and female figure are linked yet separated, and echo many centuries of renditions of Adams and Eves, especially since we can’t see her left arm or his right one where the hand-off of the apple would have been taking place. But even here we miss the opportunity to experience the owners of these well-muscled bodies as psychological beings. We can make no eye contact because they have no heads. It is odd to see these bodies and finding ourselves absolved from having to think about what the model is feeling or even what the painter is feeling. Whose bashfulness is being represented by this absence?

The headless figure was practically a sub-theme of the show. Alex Spinney has two headless photorealist nudes posing with food (or possibly “food”). Both are detailed, commercial, and creepy, in the best sense of the word. In “Realfood_1~freckles/bolognese” (2017), it becomes evident that giving the nude model something to do or to hold raises the sorts of questions to which surrealists were drawn. By what set of conventions are we looking at this naked person, anyway? If having her stand with a bowl of bolo, the pasta dripping over the side, is artificial, what is the whole picture anyway? This is pursued even further in Spinney’s “Fakefood_1~Lobster/Oyster#prop,” where the painting celebrates the sensuality of the oyster (is it fake?) even more than that of the model, who is destined to forever be without something deliberate to contribute to the scene. The oyster and the lobster turn the model into a prop: Still Life with Gold Bangle and Breasts. The work seems smart, and at least a little transgressive, about the intersection between food paintings and commercial appeal. Does the nude sell the food, or does the food sell the nude?

By contrast, Martha Gaustad’s “Down” (2017) shows a model who is allowed a full psychological presence. She is perhaps a bit older than most other models in the show, and perhaps a bit fuller-bodied, though her pose, in which she is crouching, modestly doubled up on the floor, is hardly designed to be slimming. She might belong to a different social class than most other models; when she is naked, her jewelry stands out, as does her attention to her nails. Though she is not looking at us, she seems to be deliberately looking away, a little lost in her own thoughts which seem to include acknowledging the push and pull between the demands of nudity and modesty.

Equally psychologically powerful was Tim Waite’s “Resist” (2016), a “digital composition” that seems to be based on a photograph of a statuesque woman standing, possibly, in water that has been considerably embellished with purple lines and spidery forms. It has the look and tonality of a Pictorialist work from a century or more ago. The water is so, well, form-fitting that she barely qualifies for inclusion in a show about the nude. Considering photography’s fraught relationship with female nakedness over the decades, it is interesting that she does not have a conventional body for this show. She faces us directly, but her eyes are closed. She is irritated or angry or resigned or at rest after a long and difficult day; she is lost in her inner world and look as we may, she declines to be on display for anybody. Stephanie Grenadier (who sometimes works with Waite and possibly shares models) has, in “Yes My Circus” (2017), a print of a man facing us, balancing on one foot, with his other limbs stretched out on front and in back, everything arguing for a theatrical intensity. He could be a dancer, an athlete, an ice skater, or a Hellenistic statue. There is a handprint on his back; he has been painted on, perhaps with mud. In this sepia-toned image, Grenadier—like Waite—plays with the look of century-old photographs. The model is performing in front of a perfectly visible drop cloth, like you might see in a nineteenth century carte de visite. But at the same time, the total effect is a little like one of the figures from Irving Penn’s appropriative journeys to other cultures, where the primitive was made to contrast with post-modern artifice. It seems a reminder of yet another way that the nude is defined by—or perhaps even created by–the presence of a studio.

In this show, it seems clear that to change the nude, we will have to change its context. Martin Beck’s pastel on prepared paper, “Hunter” (2016) has us still in the familiar territory of the reclining female nude, but she is not in a conventional studio. She has succumbed to gravity, lying on a bed with draperies, a modern-day Diana, possibly exhausted after a day in the forest, who has just dropped her gun. In her frank nakedness, there is a hint of Manet’s Olympia. She is asleep with her shotgun within easy reach. If it weren’t for the gun (and the title), it would be less clear what to make of the dog that lies on the floor beneath her (or perhaps floating just above it?), who is surely among the most expressive mammals depicted in the show. The dog is staring out at us, but as to what is on its mind, that’s hard to say. It is hungry, or distrustful, or rueful, or angry, or patient, or insistently curious, or sleepy. You know how dogs are. All of the painting’s representations of consciousness are concentrated in the dog. Is the whole image the dream of a sleeping dog? It does seem as if we’ve entered a dream space, as we seem to have in Beck’s “Color Field” (2017). Here a woman is in, or on, or floating just above a bed, probably asleep, possibly falling. Despite the title, it didn’t seem to me that this brought color field painting to mind, but she does seem to be about to be engulfed by the sorts of intense pastel colors used by Redon. It is as if she is about to forsake the world of her physical body and enter the world of art, a creature made by marks on a page who is about to be transported to a world of marks on a page. Beck’s work reminds us that dream space is another geography, besides the artist’s studio, where nudity is right at home.

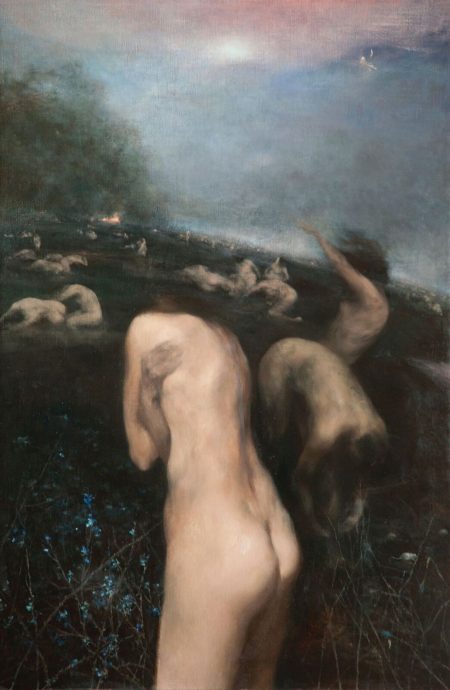

Shiqing Deng is one of the most remarkable artists in the show. “The Steps of Rebellion” (2015) might also be a dreamscape, but it is a grim one. In a vertiginous, wind-swept, smoky landscape, small groups of naked figures are gathering. They are possibly conferring, though they seem disconnected from each other. They could be Lucifer’s fallen angels (as Goya might have envisioned them) just arising from their epic tumble from grace. They do not seem headless, exactly, though their heads are a little hard to find. Lost in their torment, they are certainly indifferent to our looking at them. Are they particularly well-preserved zombies? Perhaps the figures are turning towards cannibalism–another way, besides Spinney’s, to see connections between nudity and food. It seemed like one of the most overtly political works in the show, though its exact politics would be hard to decode. There is an alarming tilt to the horizon. If the figures try to rest here, they might fall off. The picture is rich in narrative possibility, just about to be set into motion. The figures will either have to make the best of a very bad situation, or move on to someplace else. They have nothing left to lose which, the title suggests, is a first step towards rebellion.

What does the show think that this adds up to? As with most group shows at Manifest, the exhibition’s signage suggests that the works have been assembled as the result of a selective process that is complex and rigorous. “Manifest’s several-member jury reviewed 512 works by 161 artists from 34 states and 9 countries. Twenty-one works by these 16 artists from 9 states were selected for exhibition….” As a critic, I have to say that I find it irritating and possibly even disturbing that for all the meticulous attention being called to a process of curatorial intensity, the curating jury is not identified, which seems like a bit of bait and switch. And while I know that there is no intention of representing this exhibition as a survey of the nude, I would expect that after nine years of exploring a genre, the Manifest is more than entitled to make some observations about what they’ve found and possibly how it has changed over the years. If the signage didn’t call attention to the show’s selective principles, one wouldn’t miss them so much. I found that I wished that they had been identified.

Dora Natella’s bronze “Await” (2017)—one of only two sculptures in the show–is among the most polite–least edgy–works at Manifest. I want to be fair to it, but it is hard for me to see how it fits in with the rest of the show. I would have valued a bit of curatorial guidance. It is easier to see what the other sculpture here, Chris Corson’s “Self-Confidence” (2015), is doing in this company. A raku-fired torso, there is something forensic about the piece, which is missing arms, legs, and—of course—head. It ends up being both monumental and mysterious. Like a number of works in the show, it seems allusive to earlier works—it has the prominent, muscular belly of Rodin’s naked, striding Balzac. Interestingly, even with all of the most telling parts missing, it suggests an abbreviated version of a complex self that both can’t be avoided and doesn’t want to be seen.

September 25th, 2017at 5:13 pm(#)

Tim Waite and I are a couple. The “models” are each other and the poses are indeed quite psychological and about life.

They were made during a very intense time in our marriage when we were caring for my mother who had advanced dementia and was living in our home.

Pretty much everything we had was given to her and yes, I was in our little pool, sad and resigned. And yes. I meant “Not My Circus” to look like and old Photo card.

The statuesque(fat) nude is me and is quite intentional and a far greater risk than one can possibly understand. I am also the one in my photo underwater.

It references a poem by Stevie Smith.

Images do not require words but since reviews are words, I will add mine.

Here is the poem:

Not Waving but Drowning

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.

Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way,

They said.

Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

(Still the dead one lay moaning)

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

September 27th, 2017at 10:01 am(#)

As a male artist of male nude drawings I have always been discouraged at how society reacts to any type of nude works especially of the male nude figure. Show after show I see men too ashamed to stand in front of male nude art but feels safer standing to the side and sneaking peeks when he feels no one else is around. A sad state to say the least the we a man can not appreciate the art of a male nude without social criticism or a male artist of male nudes without having his own sexuality questioned. Our society states that a “real” man would never stand in front of a male nude to observe the quality or style of the work and that doing so would be totally unacceptable or have some type of depraved sexual overtones.