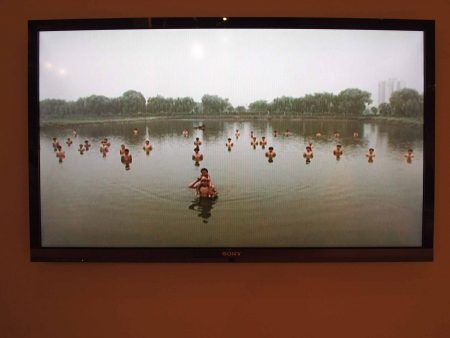

The final moments of the recording of Zhang Huan’s performance piece, “To Raise the Level of a Fish Pond,” make the piece as delightful as it is effectively critical of the economic conditions for low-wage laborers. It features 40 Chinese workers known as liudongrenkou, or “floating population,” who raise the water level by one meter with their physical presence. They don’t float—that refers to their employment status—but stand chest-deep in formation in the fish pond, eventually joined by the artist carrying a naked boy on his shoulders, literally changing their landscape.

In the final moment of the video, after they are told they can exit the pond, they break into smiles and laughter. As they clamber out of the water, silvery fish jump into the frame, displaced by their movement. The whole effect brings the viewer back down to earth; the workers aren’t art pawns, but active characters who show a moment of relaxed humanity, with fish joyously (or reflexively) leaping at their exit.

This is only one moment in “Chinese Dreams” that makes it an exemplary exhibit in Boston now, featuring contemporary Chinese artists creating work in the aftermath of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The artists were either small children when the destructive upheaval took place, or grew up in its aftermath, shaping their identities in a country that had effectively destroyed its own.

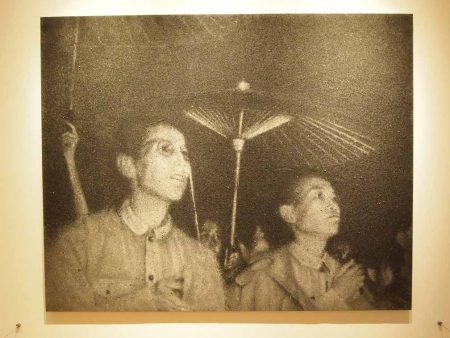

“Night” (2007) by Zhang Huan. Deriving the image from a Mao-era photograph, Huan used the ash from incense burned at Buddhist temples—which survived despite harsh restrictions during the Cultural Revolution—to create the piece.

I’m not sure if most of the eight artists featured would identify their work as “dreamy”—the edges are a bit hard for most pieces to suit the exhibition title—but “Chinese Dreams” at least quashesexpectations of Mao portraits and propaganda art, which isn’t present here. The humanity and beauty present, contextualized in a destructive past, show these artists’ range and create a beautifully textured viewing experience.

There’s a coincidentally autumnal tone to the exhibition, thanks to an overarching palette of gold, burgundy, yellow and green. Fred Han Chang Liang’s “Autumn Biophany” even explicitly invokes the season with its yellow fallen “leaves.” Three of the other focal pieces share it, too: Li Songsong’s diptych, “Public Enemy,” Zhang Xiaogang’s painting “My Mother,” and Song Dong’s ceiling-scraping yellowneon reading “That which goes undone goes undone in vain, that which is done is done still in vain, that done in vain must still be done.”

“Public Enemy” by Li Songsong (2008), “That which goes undone goes undone in vain, that which is done is done still in vain, that done in vain must still be done” by Song Dong (2007-2012)

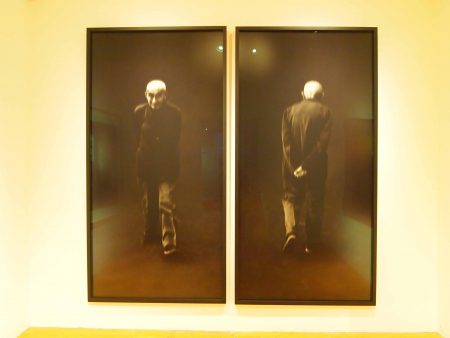

Li Songsong’s oil paintings are a formidable presence in the show, depicting well-circulated photos of Yang Jia and officials with the weapon he used to stab six police officers on July 1, 2008—coincidentally (or not) the anniversary of the Cultural Revolution. Because the murders were an act of revenge after Jia had been arrested for a minor infraction and beaten by police, both the public and the press retained an inordinate amount of sympathy for him, although he was ultimately executed. The muddled, layered oil paint in distorted colors on larger-than-life canvases reflect the complex, unseeable conclusions foregone in the brutal events and their aftermath.

Song Dong’s neon “That which goes undone…” underscores a constant theme of creating art in general: ultimately, nothing we do changes anything. This Taoist philosophy carries more weight considering that the Cultural Revolution destroyed or obfuscated much of China’s cultural heritage. The neon adage, heralding a commercial reawakening that some may call inevitable, confronts the fact that artists—and perhaps, whole governments—end up bending to “the way.”

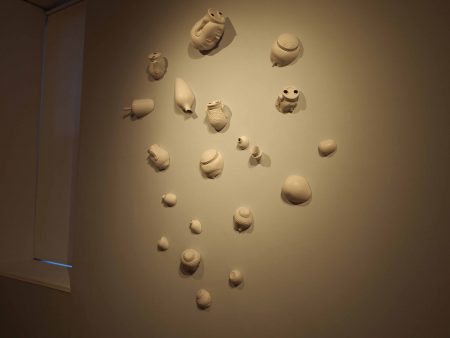

Fred Han Chang Liang takes a different approach to philosophical and cultural transitions with “Dehua White,” a collection of porcelain Buddhas and vases partially submerged in the wall. Dehua has been manufacturing these ceramics since the Ming Dynasty—their half-in, half-out state evokes the cultural exchange between east and west, where part of a thing is lost, and remains suspended. The piece was originally intended to jut out from the floor instead of the wall. I imagine that would suggest more of a fallen-off-the-table mistake; here, it’s almost like footholds in a climbing wall, destination unclear.

Two particularly memorable pieces, though, address families’ singular experiences and hardship faced during and after the Cultural Revolution. One, Zhang Xiaogang’s large painting, “My Mother,” is a somber tribute to his mother, who died in 2010. He gained international recognition in the 1990s for his “Bloodline: Big Family” series, which mimics formal family portraits from the Mao Zedong years. His mother and father were forced to leave their four sons and work in labor camps; predictably, the psychological effects of her “reeducation” took a significant toll long after the Cultural Revolution. It looms, perhaps, as large as this colossal canvas. Zhang’s child self seems to have an adult face, while his mother wears an expression of mask-like calm. An extension cord stretches and worms its way up to a light bulb, conspicuously unlit.

The other is an 8-minute video called “From No. 4 Ping Yuan Li to No. 4 Tian Qiao Bei Li” by Ma Qiusha, the only woman artist in the exhibition. She addresses the camera and recounts her childhood as the one-child policy took effect in China, and her struggle to find success under pressure from her parents, who could not obtain an education because of the Cultural Revolution. As she speaks, we start to realize that her mouth is slowly filling with blood, teeth stained by rosy tributaries. At the end of the video, she extracts a razor blade from her mouth.

It would be facile to make the speech accompanying this video aggressively political, explicitly calling out the death and destruction brought by the Cultural Revolution, or a rebellious counter-Mao speech. Instead, a straightforward story about her family’s hardship, her own struggles to live up to their expectations as the one child, and her outright affection and appreciation for their sacrifice is a highly effective contrast to her slow, deliberate wound.

That sharp edge, present in so many of these pieces, is why “Chinese Dreams” doesn’t seem to be the right phrase to describe these powerfully illustrative works. It requires, instead, that we recognize dreams for what they so often are—bright or barely-remembered traumas manifesting in unexpected, breathtaking ways that force you awake.