O.H. Willard’s Galleries, Light Artillery, Sergeant, 1866, albumen print, 8 1/16” x 5 3/16. National Gallery of Art, Washington, albumen print, 8 1/16” x 5 13/16”. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert B. Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund.

The title of the National Gallery of Art’s exhibition “Posing for the Camera” is a bit of a misnomer since quite a number of the 70-some photographs feature people caught unawares, not posing. But I don’t want to quibble over nomenclature, especially since several of my favorite photos are anything but posed.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), Lorina and Alice Chinese Dress, 1860, albumen print, 5 11/16” x 6 9/16”. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, Robert B. Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund, The Ahmanson Foundation, and New Century Fund.

When an image could be projected onto a light-sensitive ground and fixed, marked the moment photography was born. The Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre is generally credited as the first to do this, inventing the Daguerreotype in 1835.

One of the limitations of the Daguerreotype was the length of exposures needed, which ranged from seconds to minutes. This constraint allowed only for static poses. As photography evolved, processes were invented to shorten the exposure time to milliseconds and allow spontaneity to enter the photographic vocabulary.

What struck me as I wandered through the exhibition was the continuity of concerns addressed by photographers throughout every era, e.g., choice of and approach to the subject, handling, and composition. So I ping-ponged around, letting one photograph lead me back to one I’d seen earlier.

To illustrate this, let me discuss two portraits of children–the Portrait of a Child, a Daguerreotype produced by Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes in the 1850s, and Edward Weston’s 1925 picture of his son Neil asleep on a sofa.

Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes, Portrait of a Child, 1850s, daguerreotype, 2 15/16” x 2 9/16”. National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Joyce and Robert Menschel Fund.

In the earlier image, a studio portrait, the solemn young child has more gravitas than many adults in positions of power today—okay, I’ll say it, our president. She remains still during what would have been a long exposure, without a hint of impatience in her serene demeanor. But it’s hard to imagine her skipping off to play once the session is over.

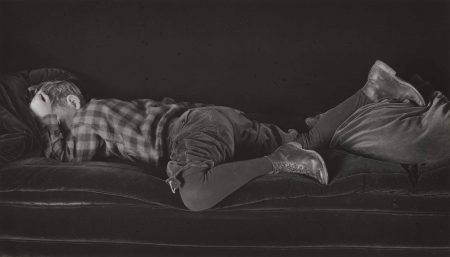

Edward Weston, Neil Asleep, 1925, gelatin silver print, 5 3/16” x 9 1/6”. Promised Gift of Robert B. Menschel.

Instead of the formality of the Daguerreotype of the young child, Weston has caught his son napping, sprawled casually on a sofa. Although worn out by playing, my guess is he’ll soon be at it again. Faster shutter speeds made it possible for Weston to capture a moment that might be fleeting.

It wasn’t only the subjects that led me to pair photographs; sometimes it was their purpose. Both Cindy Sherman and Man Ray were commissioned to do commercial assignments, she fashion shots for a boutique, and he an ad campaign for a private French electric company. But their own unique aesthetic sensibilities weren’t subjugated to their employers’ needs.

As always, Sherman used herself as the model and took the job as an opportunity to parody standard glamour shots. The label quotes the artist as saying she wanted “to make fun of fashion.” In this photograph, Sherman wears a dark tuxedo-collared coatdress but that’s not what is being showcased; it’s all about the character she is playing. Her fists are clenched, her body tense, and her face is hidden by her platinum hair with only the left eye visible. The impact is more, “Why is this mannequin so angry?” than “cool dress.” Unfortunately I don’t know if these photos were ever used, but Ray’s were.

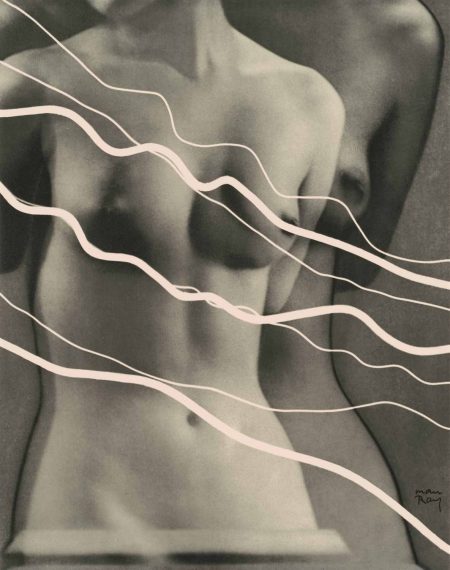

Man Ray, Electricité from Electricité, 1931, photogravure, 10 1/4″ x 8 1/16″, Promised Gift of Robert B. Menschel.

For the Companie Parisienne de Distribution d’ Electricité, Ray made a series of Rayographs, his signature technique1 for ads promoting electricity. In the 1930s, most people were still using gas, wood, or coal for heating, lighting, and cooking. Electricité features a Venus de Milo-like figure with white zaps of light zipping diagonally across her body. He projected the negative of the Venus de Milo, played by his lover Lee Miller, onto light-sensitive paper, and then laid power cords and other things over it to make the white lines that appear when the arrangement is exposed to light; they materialize the invisible electric current. 812

In a number of the photographs, starting in the 19th century and continuing into the 20th, the figure is minimized, sometimes to the point that it is insignificant or sheds detail to become an abstract, or nearly abstract, element.

In Constant Alexandre Famin’s c. 1865 Forest Scene, trees line a woodland path, their branches overhanging it to make an ogival arch, which suggests church architecture, but here nature is divine. There is a man at the center of the scene, but he is dwarfed by the trees and is only seen in silhouette.

Fast-forward a hundred years to Harry Callahan’s black-and-white pictures of Cape Cod beaches shot from a bluff far above. Those enjoying the day are merely dark shapes and barely differentiated from the boats in the water. With no identifying details, these shapes read like graphic elements.

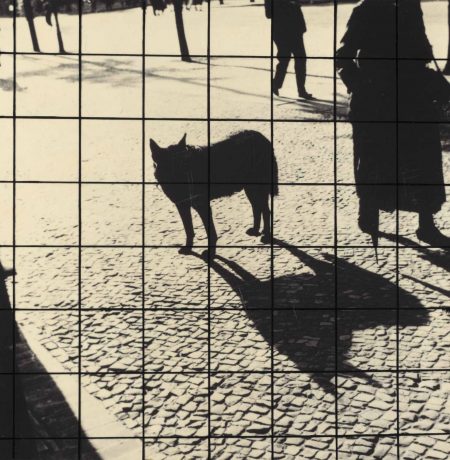

György Kepes, Untitled (Berlin), 1941, gelatin silver print with black gouache added, c. 1938, 5 13/16” x 5 11/16”. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert B. Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund.

In an untitled 1941 photo taken on the fly in Berlin, György Kepes also eschews detail for strong graphic shapes by silhouetting the participants in the scene. The center of attention is a dog, likely a German shepherd and maybe a stray. Standing on a cobblestone pavement, the long shadow he casts transforms him into a potentially menacing wolf. A hausfrau, bundled up against the cold, is caught mid-stride as she passes without acknowledging the animal. In the background, a man is walking. Energizing them is the fact that parts of their bodies are cropped out, which lends a sense of movement. They’ve been caught unawares. It’s the dog that’s posing with his head turned to face the photographer.

There are other themes to explore in this exhibition, as noted in the press materials: understanding another person’s or the maker’s own identity, interpreting cultural issues, documenting historical moments, and providing a resource for education. They are all worthwhile approaches but it was the continuity across time and through advancing technical achievements that guided me through the exhibition.

–Karen S. Chambers

“Posing for the Camera: Gifts from Robert B. Menschel” through January 28, 2018. National Gallery of Art, West Building, National Mall between Third and Ninth Streets along Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 2001. Mon.-Sat. 10:00 am-5:00 pm, Sun. 11 am-6 pm. 202-737-4215, www.nga.gov. Free.

Endnotes

1 Rayograph is Man Ray’s term for a type of photographic picture produced without a camera by arranging objects on light-sensitive paper, which is then exposed and developed.