In 2014, Zephyr launched an ongoing Project series with curated proposal-based exhibitions as well as collaborations with universities, colleges, and cultural institutions. Project 20: Failure in Progress is the twentieth exhibition in this series. Failure in Progress is curated by Jessica Bennet Kincaid, currently the Coordinator of Collections and Exhibitions at the University of Louisville’s Hite Art Institute.

Andrew Cozzens, “End Game” (2017), mixed media (wood, electron-ics motor, clay, time), dimensions variable. Image courtesy of author

At the end of the project statement Kincaid puts forth a proposal, or better yet a question, in stating that “the ambiguity of failure provides possibility for it’s recuperation, affording space for both optimism and indifference—leaving room for failure to be a fruitful venture. This raises the question, is there such a thing as irrefutable failure?”. The societal construct of ‘failure’ is based in juxtaposition with success; and if success is relative, than isn’t failure as well? As an exhibition, the works illustrate a discontentment with the idea of success, continuity, or finality especially in contemporary art. The exhibition is a curation of fifteen works from five contributing artists of varying media: Josh Azzarella (HD video works), Andrew Cozzens (mixed media installation), Gautam Rao (sculpture), Alex Serpentine (video and augmented reality interfaces), and Melissa Vandenberg (burned or charred paper works).

As you enter Zephyr’s main gallery, Andrew Cozzens work End Game (2017) expands the depth of the room and captures your focus. End Game visualizes the human desire to capsulate time: this includes our perception of time, how frail that perception is, and ultimately how unimportant that perception is. To quote Kincaid, “End Game does not allow us to confuse the suspended states of the artwork for permanence, and undermines the tendency to demarcate incremental waypoints of a process as a viable gauge of either progress or success”. End Game consists of six large clay urns placed on wooden shelves that have been rigged to individual digital clocks. Each of the urns is paired with a timer set to a different date and time, in which the vase will automatically fall from its shelf onto the floor— both fulfilling its destiny in it’s fall and ending its experience as an urn. Its’ prominent placement within the space sets a paradigm in which the viewer can experience the remainder of the exhibition. It fixates our sense of place within history utilizing recognizable imagery— the urn and the digital time clock. Shown in tandem the items remind us of technological advancement’s relatively slow pace within the 21st century— of our historically contemporary ‘failures’, and arguably our future ‘failures’.

Within the same main gallery space exists Alex Serpintini’s Almost Something (2017), which exists as survey responses visible through an augmented reality interface, allowing the viewer to manipulate the tablet in any direction within the gallery. The interface of the tablet is connected to the camera on the device so that when the viewer moves the tablet, a variety of texts appear indiscriminately over whatever the camera is pointed towards. The texts contain solicited responses to the prompt “In seven sentences or less, please tell me about something you consider a failure because you never tried”. These responses vary from contributions of relationships never developed, academic goals never achieved, and fears of the unknown. Having given the viewer the opportunity to move the tablet around the gallery, the viewer is given the capability of projecting those varying ‘failures’ onto the remaining works within the space—changing their perceived meaning. Ultimately, Almost Something reminds us that oftentimes our self prescribed failures lie deepest in our hopes that were never fully realized in the first place. Our inherent failure lies in our unwillingness or incapability of effort— loneliness or impracticality is a contributor to our lack of contentedness or intimacy.

Melissa Vandenberg’s works consist primarily (with the exception of Sew to Speak, 2014) of works on paper: images created using matches, controlled burns, and other materials. Romantic Conceit: Swallowed Pride Seres (2009) on the other hand, was created with just two melted (possibly three) popsicles on paper—anyone with a sweet tooth can recognize the reds and blues of the Firecracker—a firecracker shaped popsicle with what I’ve always assumed to be strawberry, cherry, and blue raspberry flavors. Romantic Conceit is tucked in the back corner of the gallery behind the stairwell. It’s the only work in the space with any reference to color. Its composition is organic, linear, and almost glittery in appearance. Two popsicle sticks remain stuck to the paper, their sugars bonding them to the fibers of their paper home. Romantic Conceit holds its autonomy as a memory welder. Of course the popsicle holds a specific childhood lexicon for most Americans; but the stickiness and the sense of time that is present in this work is what really attracted me to this image.

Melissa Vandenberg, “Romantic Conceit: Swallowed Pride Series”, 2009, melted popsicle on paper 29” x 22”, Image courtesy of author.

Melissa Vandenberg’s works consist primarily (with the exception of Sew to Speak, 2014) of works on paper: images created using matches, controlled burns, and other materials. Romantic Conceit: Swallowed Pride Seres (2009) on the other hand, was created with just two melted (possibly three) popsicles on paper—anyone with a sweet tooth can recognize the reds and blues of the Firecracker—a firecracker shaped popsicle with what I’ve always assumed to be strawberry, cherry, and blue raspberry flavors. Romantic Conceit is tucked in the back corner of the gallery behind the stairwell. It’s the only work in the space with any reference to color. Its composition is organic, linear, and almost glittery in appearance. Two popsicle sticks remain stuck to the paper, their sugars bonding them to the fibers of their paper home. Romantic Conceit holds its autonomy as a memory welder. Of course the popsicle holds a specific childhood lexicon for most Americans; but the stickiness and the sense of time that is present in this work is what really attracted me to this image.

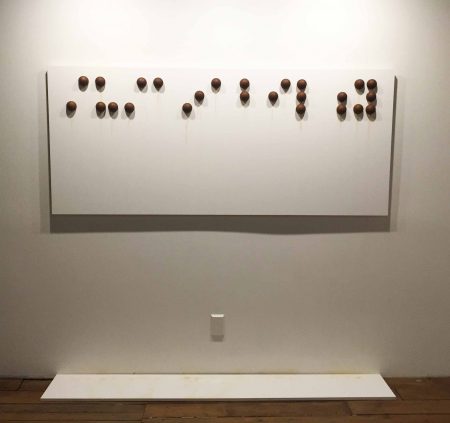

In the upstairs gallery, there is another work by Cozzens that stood out for me. Cozzens seems to have a grand skill in boiling down his existential points. Error No. 0000001 (2017) feels like a critique of our forever expanding infrastructure and it’s lack of sustainability— and a firm reminder that Earth and it’s powers will be here long beyond our futile attempts at contorting and manipulating it. Error consists of twenty-five steel half spheres bonded to a wood structure in a pattern that presents like braille (to clarify, I wasn’t able to find any information to fact check whether or not this was the artists’ intention and due to size I’m unsure of whether or not it’s very functional as braille). Error was then sprayed with water; the water working to erode the steel over time. Steel, one of the hardest man made materials, is degraded over time by water.

Failure in Progress pertains to our collective / individual experiences of failure within non-specific time frames. Scale, time, and history are fluid ideas that vibrate throughout the exhibition and our conditioned response of failing is re examined as necessary, vital, and romantic— adjectives that aren’t failures at all.

Andrew Cozzens, “Error No. 0000001” (2017), steel, water, wood, time, dimensions variable. Image provided by author.

Failure in Progress is up until December 30th, 2017 in Zephyr Gallery, Louisville Kentucky.

–Megan Bickel