There is some danger in using the word “subversive” in the title of your show: it dares viewers to reveal prudish tendencies, risking loud proclamations that THAT isn’t so subversive, oh no, not in this day and age. In 2018, who even does a double take at a 51 ¾ x 84 inch close-up of a hairless mons pubis?

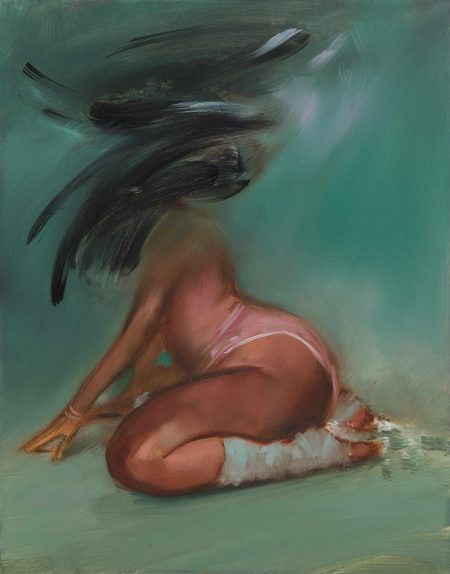

But: “HARD: Subversive Representation,” on view at UMass Boston’s University Hall Gallery through March 9, has an unfortunate fail-safe: representations of women throughout art history overwhemingly portray a homogenized, feminine ideal, composed by a male artist. To simply exist outside of those assigned roles—ornamental lover, pale victim, perpetual nude—can feel subversive.

(And I was kidding about the “double take” comment above—I’m not sure I’m looking forward to the day when genital close-ups are so common they no longer provoke a second glance.)

“HARD” features the work of 17 self-identified female artists, each depicting a female subject through varied media and interpretative approach, and invites the viewer to consider how these depictions may challenge the way we’re accustomed to seeing female representations in art. Given the diverse media and historical context in this show, it’s best to approach “HARD” as a sampler, a great to-explore list of woman artists from around the world.

“HARD: Subversive Representation” is on view through March 9. Betty Tompkins’ “Ersatz Cunt #1” is at the top left, with “Masturbation Painting #12” to its right.

The work featured here spans time, space, and theme, in evocations glamorous, domestic, and dangerous—and, yes, subversive. Consider the aforementioned piece, Betty Tompkins’ “Ersatz Cunt #1.” Much of Tompkins’ pioneering work from the 1970s onward (with a few dormant decades) dissociates pornographic images from their original context and the male gaze, magnifiying them and using paint and airbrushing techniques to form a more egalitarian shape. The cunt in question is explicitly “ersatz”—not real, a performance. But it exists, here, by itself, with no male accessory, obtrusive and demanding reverence. Despite its size, though, I was more struck by Tompkins’ other piece in the show, the smaller “Masturbation Painting #12.” The title notwithstanding, only the fingers indicate that it’s not a total abstraction, reminiscent of the first Surrealists—except with active female pleasure.

“Demonstration at City Hall, New York City, in support of gay right bill ‘Intro 475′” by Diana Davies (1973). Courtesy of the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art

Considering that a woman’s orgasm is still too controversial for R-rated films, “hard” may better translated as “difficult” in this gallery space. But “HARD” is also a response from curator Samuel Toabe to another show he curated in 2015: “SOFT,” which included fiber art (a traditionally feminine medium) by male artists, as the artists’ expressions of masculinity. “HARD” features more varied media, and the so-called texture or hard-hitting nature of the representations her are up for debate. But the tactile implications of the show title are not strictly metaphorical.

Rachel Rampleman’s “Bodybuilder Vignettes” has one of the more literal associations with that theme, with strongwomen’s “hard” bodies on display. Ten tablets (arranged, here, in a straight column) play fluid, repeating footage of the bodybuilders posing onstage at competitions, emphasizing their endurance and elegance. They’ve accomplished what is typically a male physical ideal, their muscle-bound bodies complemented with sleek hairstyles, colorful make-up, and sparkling bikinis. The result is mesmerizing; I only wish this piece took up more space in the exhibition.

“Trans and the notion of Risk: Post Surgery: #3” by Ianna Book. Courtesy of the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art

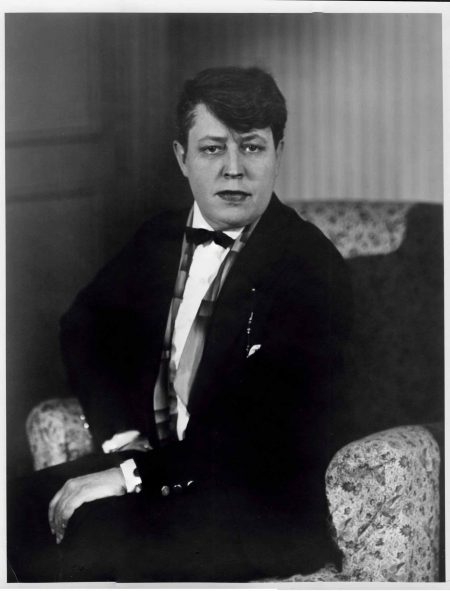

Most works were created in the past decade, but the 1923 portrait, “Jane Heap” by Berenice Abbott, is perfectly in place, and not only because queer expression through fashion is perhaps more ubiquitous today. Jane’s direct gaze mirrors the other photographed women on the wall alongside her, which includes Ianna Book’s self portrait, “Trans and the notion of Risk: Post Surgery: #3.” In it, she’s dressed for work, but still bears surgery scars. Her experience as a trans person puts her in a more immediately dangerous sense of the word “subversive.” From her artist’s statement: “Because my condition as a trans woman places me in a vulnerable position within a world still brimming with prejudice and violence, simply existing becomes a challenge, an achievement even.”

Each piece opens up a wider dialogue and context, and is a fantastic sample of women’s work—one that should invite a deeper dive. Take, for instance, Del LaGrace Volcano’s photograph of playwright Mojisola Adebayo, “Moj Minstrel Tears, Antarctic Peninsula.” The image is instantly arresting: a person of color in midnight blackface, dressed in period drag, with tears streaming down her face. Add Antarctic wilderness to that whirlpool, and it’s a layer cake of conflicting identity.

But beyond the immediate subversiveness of blackface, and the emotional pull off a crying subject, the context raises new questions: this is a scene from one of Adebayo’s plays, “Moj of the Antarctic: An African Odyssey,” wherein she plays Ellen Craft, an American slave who disguised herself as a white man to escape to freedom. The photo, while arresting as an individual piece, is only the surface of the story.

Crying is an act that historically (and currently) dismisses women as hysterical or manipulative. One other photograph depicts a tearful woman: Christine Neptune’s “What Was Taken 02.” The woman, unmistakably contemporary in her scarf and coat, presses fingertips against an otherwise unseeable glass wall, her breath only slightly fogging up the pane. Her open-palmed, raised hand is pleading, her face bracing in anguish. Through the full series, Neptune spotlights the communal effects of depression, trauma and the mythos of “the strong black woman” in communities of color, in an environment of systematic oppression. Even on its own, the photo’s emotion is striking, the subject subversive in her vulnerability—an attribute often not afforded to women of color, in favor of the “strong black woman” trope.

But there is no uniform emotion to “HARD,” which is by design—perhaps because “emotional” or “soft” are often backhanded compliments aimed toward women artists. Here, woman is timeless, cosmic: Summer Wheat’s “Infinity Dolls” chronicle the female form from embryo to crone, in flat, black, universal expanse. Janet Loren Hill’s “Common Scolds,” soft multimedia sculptures, convert the 16th century torture device used to punish gossipy or opinionated women into colorful, mounted trophies—one uses rape whistles as a decoration. Even woman’s mythological imprint, Eve, makes an appearance: “Eve After Fragonard” by Samantha Fields is a wall-hung sculpture made largely of fabric, beads, and artificial foliage. Evoking Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s famous 1767 Rococo painting, Fields turns the rosy mistress’s billowing skirts to a flat, demure rectangular weaving, still adorned with ornamental beading, though nowhere near a Rococo excess.

Eve, here, is calm in stasis, observant; and her fig leaves have fallen to the floor. The women of “HARD” may be beautiful, but their diverse sources of power remain in tact.