“In a sense it’s just ridiculously irresponsible to try to work as an artist.” —Bill Daniels

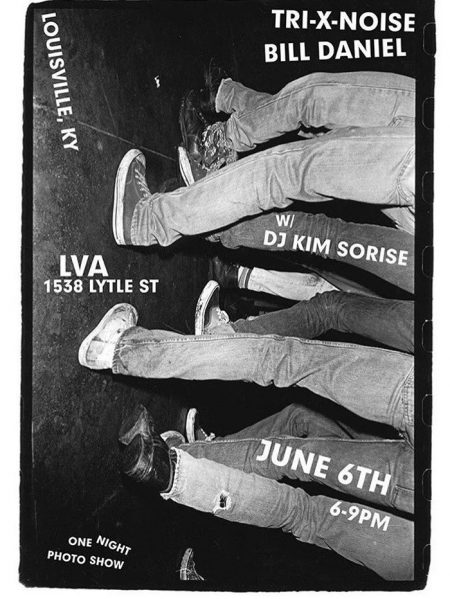

If you were shuffling around the Portland neighborhood in Louisville, Kentucky during the first week of June, you heard rumbles that an artist by the name of Bill Daniels was going to steamroll through with a one-night, bombastic, fully assembled pop-up exhibition of photographs documenting punk, skateboard, and hobo subcultures. He’d arrive in a van, pop up shop, and then exit with little more than a whisper and a boom.

Bill Daniels’ bio introduces him as a “Texas-born, San Francisco exiled, and confirmed tramp that continues to experiment with survivalism and bricolage in his attempts to record and report on the various social margins he finds himself in. Currently based on the Texas gulf coast, Daniel divides his time between Texas and touring”. Daniels received the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 amongst a list of other accolades and has exhibited extensively, including but not limited to The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The New Museum, and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco. Somehow straddling the line between nomadic ruffian and accomplished academic, Daniels work respects the practicality, hopefulness, and anxious-over-eager energy of all of those who have said, “Fuck, it I’m doing it exactly the way I want and I’m going to see more than everyone else. And that’s valid.” For that I give him praise and I thank him for steamrolling through.

The exhibition, otherwise known as the Tri-X-Noise Tour (the tour also functions as a book launch for the accompanying text titled, Bill Daniel: Tri-X-Noise and The Mainland by Lila Lee) was held for a brief three hour reception. The exhibition was composed of 35 mm, black and white photographs depicting everything from punk concerts, train hops, skateboarders, art openings, and house happenings, to balmy summer evenings with friends, cheap beer, and cigarettes. All were arranged on collapsible walls folding in a variety of zig-zag lines around the gallery. The images, all framed within black or white matte board, were arranged in a checkered pattern upon the folding walls. The pop-up was partnered with a performance by local DJ Kim Sorise who focused on distributing their quiet, folksy, low-fi, ambient post-punk variety: The perfect musical adjacent to the exhibition.

The space was provided by Louisville Visual Art, within their warehouse space where they typically hold exhibitions for their Children’s Fine Art Program. Tri-X-Noise strung together in a matter of days between a handful of people. Friends of Bill Daniels contacted Gill Holland, a local film producer and developer, who reached out to two hyper-active participants in the brewing arts / activism community within Portland: Katy Delahanty and Danny Seim— who worked diligently to arrange an exhibition with LVA in a matter of days—proving that sometimes hustle beats the hell out of proper planning.

Because I was fortunate enough to know this lovely handful of people, I was able to chat with Bill. We briefly discussed his influences and evolution as a traveler and artist, his work practice, and how those things have been affected by his lifestyle. . . and whether or not he craves junk food whilst on the road— a forever curiosity of mine.

Megan Bickel: What came first: the photography / film work or your participation in the variety of punk/ other subcultures that you document?

Bill Daniel: Like so many stories mine starts with punk rock—I was a kid who had not had much exposure to art and the world of ideas when I started going to punk shows in Austin, Texas. I began shooting the scene and that was my first taste of participating and documenting cultural, or rather counter-cultural activity. About this time I saw my first few Les Blank films and that sort of set the path.

MB: Have you been actively shooting while on the TRI-X-NOISE tour?

BD: I wish! That would be exactly within my mission statement— to be producing documentation during this mobile aspect of my work—but dammit, it’s just too much work trying to keep an exhibition tour rolling every day. I haven’t had the opportunity to slow down and get the camera and flash and get into that picture-making headspace.

MB: As of now, you’re about a month into this year’s tour. How long do you intend on traveling with this work and what is its final destination, if anything is planned?

BD: That’s the big question at the moment. Reboot this absurd tour for another season this fall, or try to find a place to live and a job and a normal way to live. It’s a toss up. I do love touring and throwing as many shows in a month as possible, but I have another life’s worth of projects that touring precludes. Kinda looking forward to stationary work again.

MB: Your photos share some of the same dynamism, power, and intimacy as those of Stephanie Chernikowski and Bob Gruen; who would you say are some of your photographic influences?

BD: That’s wonderful that you would cite Stephanie Chernikowski. She is my favorite photographer of this era and subject. Exactly, her photographs have a rare combination of graphic and technical strength and that insider’s intimacy. There is a lot of photography from the era in New York, but hers are my favorites. She’s also a fellow Texan.

Personally, I have a bunch of photographer guides in my life. [Gary] Winogrand, of course—he taught at The University of Texas a couple years before I took some classes in the department, and his influence was still very present. One the other side of my brain is Eugene Atget, who has been a constant in my life, and which led me to a deeper study of Berenice Abbott who made great, under-heralded work and left a life example of struggle, determination and just being the perfect misfit.

MB: How did you sustain yourself financially and mentally while traveling on the road?

BD: Financially, it’s photo print sales that float the boat. I haven’t yet managed to get a solid ride on the institutional support carousel. Mentally, it used to be a combination of bourbon and 5-Hour energy shots, but now it’s more like rice cakes and water. Also, I don’t listen to the radio while driving—as kind of a mental energy conservation thing. Throwing an art show several times a week in different cities is just incredibly mentally draining.

MB: Cheesy question moment: What was your most memorable moment in the thirty years that these photos were shot.

BD: Too many to tell. As Nosmo King once keenly observed, “every hour is a story that takes and hour to tell”; but I guess one moment that stands out in relation to this question is an epiphanous blurt I had while driving some tour one time, “I Can’t Remember The Last Time I Knew Where I Was!” That became a t-shirt and a sticker.

MB: What was the snack / beverage / whatever that you craved the most when you were freight hopping?

BD: I’m the most un-craved affected person. On my first freight trip I packed pretty poorly. Somehow brought like five pounds of yogurt-covered raisins and not much else. By the time I got to LA I was done with that food for life.

MB: What risks have you taken in your work, or for your work?

BD: Poverty. Without a doubt that’s the biggest, most sustained risk. In a sense it’s just ridiculously irresponsible to try to work as an artist. Poverty is, of course, widely relative, I have by luck of birth certain social advantages. But those don’t pay rent, fuel, or health care. It would have been cooler if I had an artistic answer for this question, haha!

MB: Do you see your work as relating to any current movement or direction in visual art or culture?

BD: That is something that I’m presently trying to figure out. I have affinities and peers in really divergent arenas. My goal is for my work to be operating with archive and formal functions.

MB: What does a routine look like for you, if there is any? What do the practical, boring bits of being an artist (i.e correspondence, grant writing, and, just, general time for thought) look like when you’re living a transient existence?

BD: There’s really two distinct routines: One is at home in the studio, which includes a healthy amount of trips to the beach on the bay and a lot of darkroom time. The tour routine is 90% trucker-style gnarl broken up by moments of social fun at the shows. I like both parts a lot.

June 2018

–Megan Bickel