If there’s one thing the Taft Museum of Art is known for, it’s the museum’s history. Home to the art archive of late and great Cincinnatians Charles and Anna Sinton Taft, the museum is a history rich capsule of people, place, and objects. Making her mark among the masters and makers is Duncanson artist- in -residence Vanessa German. A storyteller at heart, German narrates the human condition through her sculptural body of work, running with freedom. But what German is saying is just as important as how she is saying it, and it’s the latter that allows her to do the former. Through collecting and thrifting, the artist uses items found in her natural and local environment to build her sculptures. As whimsical and happenstance as this approach may seem, the outcome is anything but. Pointed and advantageous, the artist’s collection of material yields telling manifestations of the world around her. Dealing fervently with the abject, German organizes the found into a fury of observation, bringing race, gender, and personal narrative to the forefront of her work.

Glitter and gold and all things old

A fem-forward artist, we see at the center of each sculpture a woman, or at least implications of one. Inherent in the work is this examination of identity as it pertains to gender, anatomy, and social roles. Undermining and fab-ulizing all things feminine, German flips the script on norms and floors. She wields the world of womanhood to show us the harrowing reality of female objectified and religio-fied.

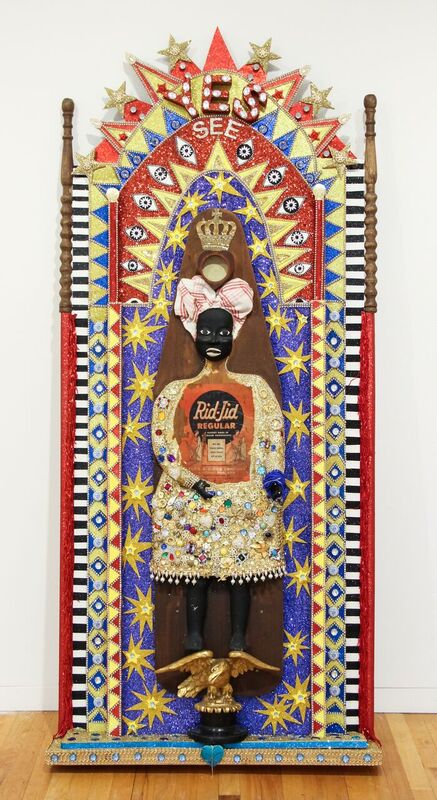

Vanessa German, Rid Jar Regular, “For Alla The Ordinary Witches & Their Soul-Ironing Jobs”, 2017, found-object and mixed-media assemblage, 81 x 34 in. Image courtesy of the artist, Pavel Zoubok Gallery, New York, and Concept Art Gallery, Pittsburgh

Mounted as a saint on an altar, Rid Jar Regular, For Alla The Ordinary Witches & Their Soul-Ironing Jobs, utilizes the temporal to summon the incorporeal. Iconic and clashy, German indulges in holy and domestic ritual to confront the notions of womanhood found across religious and cultural platforms. She accomplishes this through the physical structure of the sculpture and through the procurement of found material. We see this in how the female figure is fixed centrally in this crucifix-like composition, ever so lustrous and omnipresent. We then see the components of which she is comprised – a cleaning rag, a bedpost, and an ironing board with the promise to “not wiggle-wobble, joggle, slip or slide.” Suddenly the figure is no longer human but rather a relic of service and duty. She shifts between humanness and inanimacy to communicate the disparity between the two. It’s this sort of bait and switch tactic that is central to her work; she draws you in with a lot of sparkle and shine and then she makes you think.

Clara Peller tells all

Throughout German’s body of work we see very socially and politically charged messages that, depending on the lens through which you view them, can bend or break however you please. Tapping into the innocence of youth and childhood, German takes us back in time to that vulnerable place where her work becomes a little more personal and her banner inarguable.

Vanessa German, “white american cheese”, 2014, found-object and mixed-media assemblage, 41 x 24 x 7.25 in. Image courtesy of the artist, Pavel Zoubok Gallery, New York, and Concept Art Gallery, Pittsburgh

Small and sentimental, white american cheese stands but several feet tall among the more monumental figures in the gallery. Its quaint size and doll baby complex remind us of a time of fragility and innocence where anything is possible and everything imaginable. There’s a sort of fantastical quality to it that brings out the child in all of us, breaking down the feigned walls of adulthood and growing old. This breeching of our senses allows us to relate to the artist in a very personal way, making her experience our very own. We begin to ponder the weight of whiteness as the “Mel-O-Bit White American Pasteurized Processed Cheese” box protrudes from the contrasting black figure’s head. We read the 1980’s mantra “Where’s the beef?” button and begin to consider the passing of time or lack thereof and how the climates and issues of the past may be just as prevailing today as they were then. We see the skateboard and remember play and how our formative years impact us even still. And if that were not enough we look to the back of the girl who bears a mirror for us to (literally) become a part of the piece, making this sort of cathartic experience shared and communal.

location, location, location

The narrative continues down the hall with arguably the pinnacle of the show. Standing loud and proud is German’s I Am Reaching For The New Day. On display a- part from the remainder of the exhibition, this sculpture is fixed exclusively in the Longworth Foyer. But this particular foyer isn’t just a foyer. Instead it serves as a transformative backdrop not only for the singular sculpture, but for breadth of the body of work, too.

Vanessa German, “I Am Reaching for the New Day”, 2017, found-object and mixed-media assemblage, 82 x 74 x 27 in. Image courtesy of the artist, Pavel Zoubok Gallery, New York, and Concept Art Gallery, Pittsburgh

History tell us (aka those helpful plaques gracing the walls of museums everywhere) that Nicholas Longworth commissioned artist Robert S. Duncanson for the landscape paintings adorning the present-day foyer. History also tells us that Duncanson was a pioneer in his field, being the first African-American artist to achieve international acclaim. Juxtaposed in the center of his 19th century panorama, German’s sculpture obstructs and constructs the surrounding hillsides and all their implications.

Appropriately named and purposefully placed, I am Reaching for the New Day complements this historical happening. Paying tribute to Duncanson as an African-American artist as well as the appointed Duncanson artist-in-residence, German sort of memorializes his legacy through her sculpture. Preemptively? No, but by way of curation and location, the two artists are now bound together. But German reminds us of the past and the present and the road in between. Her sculpture is a visual paradox of remorse and celebration, triumphs and hardship. We see this in the bright but tattered garb, in the stilled movement of the figure, and in the suspended noise of the megaphone. Her sculpture then, is a silo of sorts, holding to the new day that has been reached, while beckoning the day that is still being reached for. It’s a perception of progress and a lovely one at that.

No End

To limit each piece to being ‘about’ a single thing would be too plain. Just as her personhood, Vanessa German’s body of work is dynamic, complex, and vastly intertwined. But as equally as unjust as the former, would be to omit her overt call to attention and action for the communities and experiences from which she draws so strongly upon. running with freedom is a provocative and honest deliberation of self and surroundings. Through her daring lack of convention, German re-imagines the mundane for the sake of making and liberating. If you’re an artist, an activist, a feminist, or any other sort of ‘ist’, this show is for you. See it now through October 21, 2018 at the Taft Museum.