“The Fabric of India” exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum illustrates the country’s diversity through 170 handmade objects dating from the 15th century to today.

“Flower Border” (det.), silk velvet with silver-wrapped thread, poss. Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 1640-50, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The show, co-curated by Rosemary Crill, the senior curator in the South and South-East Asia Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), and Divia Patel, is arranged around six themes: courtly splendor, religion, international trade, client/ artisan relationship, political symbolism, and contemporary fashion.

The exhibition is accompanied by a hefty and lavishly illustrated book with insightful essays. I particularly liked the “Object in Focus” discussions.

“Turban Cloth” (det.), tie-dyed cotton, Rajasthan, prob. Jaipur, ca. 1866, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

India is many things but homogeneous is not one. The regions of India have produced their own distinctive textile traditions with available raw materials and developed unique weaving and dying techniques and forms of embellishment.

India developed a lively global trade and catered to the tastes and needs of various cultures. For example flowery chintzes were popular in Europe, Madras-checked cottons were exported to West Africa, and ikat from the southeast coast went to the Persian Gulf, etc.

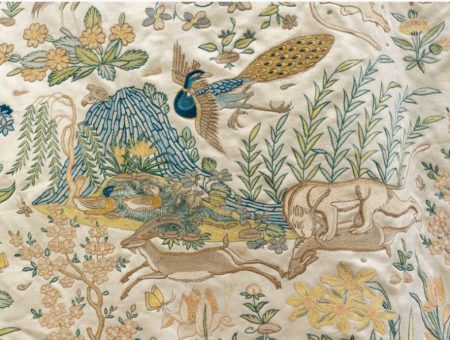

“Riding Coat” (det.), silk (satin weave) embroidered with silk, prob. Gujarat, 1620-5, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The exhibition is presented in two large galleries, which is perfect for this exhibition that also has two halves. Enter the gallery on the left, and you’re confronted with a pedagogical display that tells you everything you ever wanted to know about Indian textiles. Through discursive labels, wall text, photographs, and videos, which are invaluable in understanding a technique, you are taken step-by-step from raw material to finished product. But there is just too much to look at. I gave up and decided that if I was drawn to a finished item, I could just backtrack to learn about the materials and techniques used.

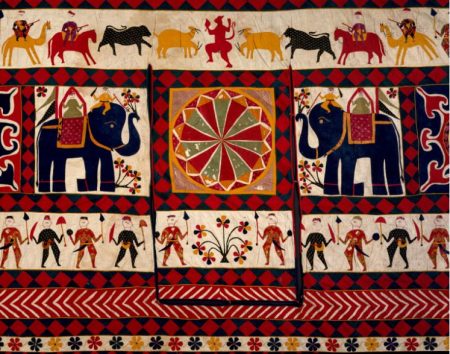

“Wall Hanging” (det.), cotton, with silk and cotton appliqué, Saurashtra, Gujarat, 1920-40, Given by Mr. and Mrs. Jerome Burns, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Certain to be the most popular place in this section is the room where you are surrounded with wall hangings–bihitiya–made by Gujarat’s Kathi community. Appliquéd with silk and Western cottons on a cotton ground, they were intended to decorate a room for a festival or wedding. It’s like recess, an escape from your lessons.

I expected to be wowed by the second part of the exhibition but was underwhelmed. It was wise of the exhibition designer to put what is clearly the pièce de résistance-–the wedding dress by contemporary designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee–not at the front of the gallery but around a corner.

“Gujarati Embroidery”, cotton embroidered with silk, Gujarat, 1680-1700, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The curators covered different time periods and different regions to present the diversity of Indian textiles. There are religious and decorative hangings; coverlets and other items for the home; shawls and clothing meant for the domestic market and for export (I wish I had a photograph of the stunning 1750s English women’s jacket and petticoat, each fashioned from a different richly patterned, printed-cotton chintz with its characteristic allover pattern of exotic flowers with a fanciful bird or two), and contemporary fashion.

But everything is overshadowed by that wedding dress.

“Female wedding outfit”, designed by Sabyasachi Mukherjee (b. 1974), silk and cotton with “zardozi” gold embroidery and semi-precious beads, Kolkata, West Bengal, 2015, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

For Hindu weddings, traditionally three-day affairs, the more bling the better. The sumptuous wedding gown on view is encrusted with gold embroidery (zardozi) and semi-precious stones. The groom’s outfit is more restrained since he would never outshine the bride. Still he’ll grab attention when he rides in on a decked-out white horse.

Sabyasachi Mukherjee, a popular designer of wedding finery, is known for combining the traditional with a contemporary take. This costume features various embroidery techniques (zardozi embroidery with metallic gold thread and kantha, a running stitch), silk, and hand-woven khadi as the lining. With his extravagant designs featuring intricate forms of embellishment, Mukherjee helps keep the traditional techniques from being lost.

The exhibition designer made a curious choice–or maybe not– by putting two 1938 political cartoons to the right of the magnificent wedding dress. One depicts a skeleton tapping on the shoulder of a weaver. The text reads in Hindi (I believe) and English: “Support and save your starving weavers by the use of handloom products.”

It makes the point that imports of machine spun and woven fabrics from England nearly killed the Indian textile economy.

But those plus a couple of examples of khadi, the hand-spun and woven plain-weave cotton that became the symbol for the Swadeshi–“one country”–movement to win independence from British rule (raj) are the only tangibles to illustrate that fight. The curators leave it to the rather long didactic material to tell the story.

“Ikat Sari”, designed by Hitesh Rawat (b. 1977) and Avanish Kumar (b. 1985) for Jiyo!, silk (weft ikat), Pochampally, Telegana, 2011, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The final section of the exhibition showcases contemporary apparel design; fine, but 23 out of the 170 items on view seems excessive. The curators wanted to show several things: how Indian traditions are being appropriated by Western and native designers, that once anonymous craftspeople are being recognized, and that artisans are becoming designers themselves.

“Houndstooth Sari” (detail), designed by Abraham & Thakore, woven in the workshop of Sri Govardhana, Puttapaka, Telangana, silk (double ikat), 2013, Given by Abraham & Thakore. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

(David) Abraham & (Rakesh) Thakore met at the National Institute for Design (NID) in Ahmedabad and have become known internationally for their soft-spoken modern design sensibility combined with the rich traditions of Indian design and craft. They credit the artisans who help realize their vision, in this case, the workshop of Sri Govardhana for the double-ikat silk.

“Ensemble”, designed by Dries Van Noten (b. 1958), cotton, printed silk, silver beads, sequins, 2008, Given by Dries Van Noten, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Well-known Western fashion designers have been inspired by the rich textile history of India and incorporated it into their designs. The Belgian designer Dries Van Noten has worked with highly skilled Kolkata-based artisans since 1987. Here the jacket is adorned with silver beads and sequins, traditional embellishments, and the skirt is handmade silk.

Another development in Indian fashion echoes the Studio Glass Movement, born in the U.S. in the 1960s. There the goal was for the artist who conceived the design to execute it, not direct an artisan. Aziz Khatri (b. 1978) comes from a family of dyers who had worked for fashion designers. He attended Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya, a design school for artisans, and now conceives and produces his own designs.

Any exhibition with a title like “The Fabric of India” courts disaster. It promises a comprehensive look that is simply impossible to realize. I do commend the curators for tackling this monumental task, but it pains me to say that after a couple of hours in the exhibition, I walked out bored by the educational component (it may completely engage another visitor) and disappointed by the second half of the show (maybe I’m just shallow). I suggest you make up your own mind about this ticketed exhibition.

–Karen S. Chambers

“The Fabric of India,” Cincinnati Art Museum, 953 Eden Park Drive, Cincinnati, OH 45202. Phone: 513-721-ARTS (2787); www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org. Open Tuesday-Wednesday and Friday-Sunday, 11 am-5 pm; Thursday 11 am-8 pm. Ticketed exhibition: general public (18 and up), $12; children (6-17), $6; college students with valid ID, $6; free to CAM members and children under 5. Open through January 6, 2019.