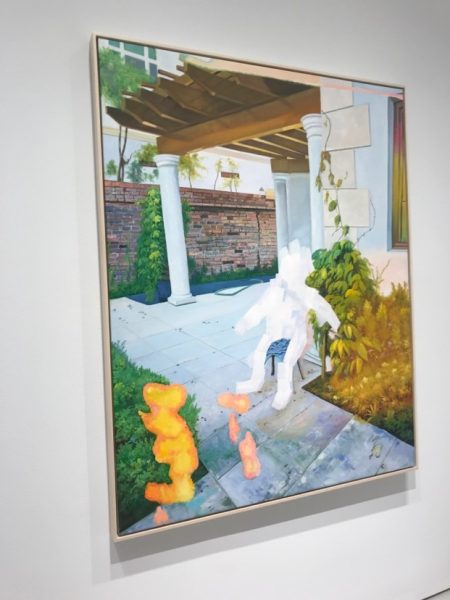

Harmony Korine’s second show at Gagosian Madison in the last six months, closely following “Blockbuster” (which ran from September – October, 2018), “Young Twitchy” (showing from March 14 – April 20, 2019) is a step in both a more formal painterly order and, arguably, in a direction that runs parallel to Korine’s recent filmic interest in the Florida microcosm. “Blockbuster” consisted of mounted sculptural installations – Korine painted thick, verisimilitude-bedaubed characters with oil stick, spray paint, and house paint on tattered videocassette boxes modularly constructed to form cartons; while “Blockbuster” contained some interesting quotational mirth, “Young Twitchy” finds its home in musings of domestic lassitude (“aesthetics of the banal”). These oil paintings were constructed from images that Korine took via iPhone in his Florida home, where “light creatures” (Korine also calls them “alien-friends”) overhang the “cosmic tropical playgrounds” that include a pool deck, boardwalk, kitchen, patio, beach, and bus stop. In comparison to his previous visual art, Korine’s paintings are technically impressive, featuring Alberti’s perspectival vanishing points and architecturally rendered monuments. Although this is Korine’s foray into a more methodological and less abstracted survey, the paintings comprising “Young Twitchy” are also characteristically playful. Pet dogs and collapsed bus signs adorn Korine’s neighborhood streets where ghostly apparitions coat the canvas – at times Korine’s paintings veer towards the indexical (e.g. globular and post-impressionist streaks) and, at others, adumbrate their materiality (swerving closer to photorealism).

Yet, “aesthetics of the banal” also may not be an entirely accurate way to describe Korine’s “Young Twitchy” as his recent compulsion for all things domiciliary is laminated by a sharp, urbanist commercial neon splendor – the same hyperrealist penchant that Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon (2016) basks in. Until recently, Korine’s cinematic directorial output made dexterous use of lo-fi formal experimentation – from Gummo (1997) to Trash Humpers (2009), Korine unveiled the gritty Americana of “abandoned parking lot(s) and a soiled sofa on the edge… with a street lamp off to the side” via pixel-picture quality films captured with the “worst cameras possible” to achieve poetic “odes to vandalism.” (Kohn 2016). Closer to the late Jonas Mekas’ “home movies,” this drug-addled young Korine was equal part direct participant and documentarian of the ethnofictive, half-fictional/half-vérité outsider cultures he authored within. With a penchant for the youthful rebellion and outsider culture brimming in Los Olvidados (Luis Buñuel, 1950) and Pixote (Hector Babenco, 1980), brewing in a particularly abysmal American broth, Korine has always espoused the playful and bizarre – such is the case in Into the night (2002), where Korine tours his hometown, Nashville, Tennessee, with Parisian Gaspar Noé. Korine opts to introduce the French director to a band of magnetic adult outcasts who live with their parents in desolate shanties rather than guide any modicum of a conventional tour – one can’t help but by being impressed by the vivacious, chipper Korine’s imminent disregard.

“Young Twitchy” settles on a significantly softened Harmony Korine, albeit with some interesting auterism still flickering. Korine has mellowed out enough to enter the blue-chip art circuit and has become something of a Gagosian homebody – his name is regularly listed alongside Georg Baselitz, Ellen Gallagher, Andreas Gursky, Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, Anselm Kiefer, Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Taryn Simon, and Rachel Whiteread come the annual Art Basel jubilee. This exhibition is in closer conversation with Spring Breakers (2012) and The Beach Bum (2019) than Korine’s previous output – even though these two motion pictures feature a superstar cast of Disney luminaries and Hollywood personages, they are braced by a gauze of reflexive, self-aware ethereal hyperreality. Similarly, “Young Twitchy,” with its banal backdrop of Miami suburbia, is shored by modish apparitions and Korine’s newfound obsession with the psycho-geography of Florida and its blurring pink sky. The figure that appears in Korine’s photograph “Yum Yum” (2018) (see Figure 1) reappears in “Young Twitchy” (see Figure 2) – “I don’t exactly know who he is or what he is,” Korine notes in a Gagosian interview, but the mythos of this omniscient-yet-affable figure has been one that the artist has carried with him since his childhood years (living in a Trotskyist Panama commune). It is this mystical character (assumedly the eponymous androgyne embodying “Young Twitchy”) who carries Korine’s vapory pathos of this “Florida period,” piping the nostalgia for a saccharine coral Miami Beach fantasy.

In his Cahiers du Cinéma September 2013 article on Spring Breakers, “Of Vulgarity,” Dork Zabunyan writes that: “The baffling effect provoked by a film like Spring Breakers results from a double capacity to show the vulgarity of its world and to question it from within, without the critique adopting a mocking tone or taunting. It is sufficient to recall what we already know – the director’s interest in outsider communities and/or eccentric youth. Rather, Spring Breakers presents the question of discovering something startling via filmic repetition, without Korine’s staging devolving into flat mimicry or a kind of ‘magma pop.’…Korine’s solution is to render the protagonists’ vulgar behavior sensitive – to, without ostentation, reveal the sluggish world that supports them. Without this critical dimension, which asserts itself almost imperceptibly, Spring Breakers would solely points towards reality.”1 (74).

We see this same critical technique arise in “Young Twitchy,” where the quotational “looping,” or repetition of otherworldly motifs, reveals the banal, “sluggish” supporting world. In “The Conspiracy of Art,” (2005) Jean Baudrillard describes what it means to “pass through the looking glass,” whereby images no longer provide a mirror for reality but, rather, swallow the mirror, whole, and transform it into hyperreality – “from screen to screen, the only aim of the image is the image – [the image can] no longer imagine the real because it is the real: it can no longer transcend reality, transfigure it or dream it, since images are virtual reality.” (120). Virtual reality, in short, presents the real without an original referent (this early concept of virtual reality poses transparency without object – a pure luminescence, completely present to itself and its own visibility). Korine’s “Florida films” in their nostalgia, are betoken by an operative hauntology that insists on “the lost referent,” fascinated by itself “as a lost object as much as it (and we) are fascinated by the real [as a lost referent].” (Baudrillard 1994, 47). Spring break, as a processual libertine study, is the perversion of a fever-dreamt “Miami of the imagination,” which comes to symbolize an immersion in the monstrous (or vulgar). Korine’s method is repeating – repeating images, motifs, shots and dialogue until they are drenched in confectionary pop-chorus echo (and the original referent is frittered).

Arguably, if one is not familiar with Korine’s more recent films, they will not be wary of the embedded hauntological premise of “Young Twitchy” as nostalgia as disruption of time, the floating “apparition form, the phenomenal body of the spirit, that is the definition of the specter,” (Derrida 2006, 169) whereby the ghost is the phenomenon of the spirit that rattles the chains for paths unactualized. Rather, for the uninitiated, Korine’s works may pass as photo-paintings heeding methodology and little else. Yet, behind Korine’s praxis is Gerhard Richter’s methodology – “blurry renditions of banal photographs of everyday life” (Foster 2004, 174) – who is perhaps the seminal practitioner of Derrida’s “archive fever.” Richter’s projection-paintings penetrate the semblance of the commodity-sign, an order of figuration, where simulation might be taken to trump both representation and abstraction, to undercut the referential claims of the first as well as the metaphysical claims of the second (restoring a “piercing referentiality to flimsy representations”). (Foster 165).

However, Korine’s photographic gesture is of a different moment: it is in the era of the iPhone archive – “Young Twitchy” enumerates a photo gallery comprising documentation of Korine’s domestic life (pet dog, kitchen, poolside, patio) and neighborhood. Before the canvas, they “appear,” initially, on the smart phone screen, where Korine has assumedly etched his ghostly figures via Photoshop mobile or some other photo-editing app before painting them. Thus, we have, beside the archive, the database: on the one hand, “the freedom to create new orders of being that comes from random access, and on the other hand, the pressure to find new levels of generality and constraint.” (Elseasser 2014, 108). Richter’s analog photo is transfigured to Korine’s personal archive by way of meta-data – the digital photo, while interfaced (and, consequently, “imaged” and “intermediated”), ontologically exists as a subterranean tract of ones and zeros. In order to cope with the sheer quantity of information, memory and trauma are “made into useful concepts” by big data, with mobile photo-editing posturing a human face via the experiential dimension comparted to the information deluge of data.

The archive is not some neutral repository of documents (Wunderkammer), but imposes its own power structures and meaning-making mechanism. Social media testify to the outsourcing of the digitized personal archive – inner and outer lives, daily routines, and precious sentiments are posed “database logics,” whereby calculus and algorithmic preference-routines inexorably corrode what Thomas Elseasser deems history’s “two main functions:” 1.) To assure us of our place and identity in the succession of generations, and 2.) To allow us to anticipate the future by learning from the past. (108). Thus, history is at a constant risk for assessment via data-mining and information-management, which patrol the borders of the personal archive – the banal is silently collected and marshalled in support of present political needs or national imperatives.

The photograph, thus, cannot be reduced to techno-perceptual, techno-optical existence; it’s relationship with painting is more complex than Richter’s unidirectional projection’s pantomime. “Photography liberates painting,” though not by apportioning the imaginary to painting (as those vexatious contemporary painters who allege cathartic purgation profess with their head in the clouds). Rather, by showing painting that “what it believes it paints is a false real, and in dissolving the prestige of perception on which painting believes it nourishes itself,” photography not only frees painting from the real, but photography frees the other arts (Laruelle 2011, 122). Conversely, when digital photography functions as a database corollary, it enslaves the other arts. Laruelle makes the distinction between the “‘coded’ image (painting), the ‘objective’ or absolutely true image, and the ‘normed’ image” via their midpoint, the photo, which supposes all of these presuppositions united together. (114).

Korine, in positing the banal everyday photo-archive from the digital database back to the canvas, is withdrawing from photography’s proximity with science and attempting a bit of humanist play (his signature gaiety – Korine’s playful kelpies and wraiths further underscore this point). Furthermore, this is what Korine can do with painting that he could not achieve with film – painting, as “the analogical art par excellence,” (Deleuze 1981, 95) can gesture towards withdrawal. Whether painting is successful in this regard, is open for debate, however. Given the ubiquitous terms of big data’s domineering mining strategies, which render innocuous play and the aesthetics of the banal as further “data imaging the world,” I would conjecture that, lamentably, it is not.

Notes

- This translation is my own. I thank Dork Zabunyan for bringing his essay to my attention during his visit to Columbia University in the Fall of 2018, when he presented his first book that has been translated into English (by Clare O’Farrell) “Foucault at the Movies.” (2017). The original French text for “De la vulgarité” reads:

L’effet de sidération provoqué par un film comme Spring Breakers résulte d’une double capacité à montrer la vulgarité d’un monde et à la mettre en cause de l’intérieur, sans que cette critique n’adopte pour autant le ton moqueur de la raillerie. Il ne suffit pas de rappeler ce que tout le monde sait déjà, à savoir l’intérêt de son réalisateur pour toute une jeunesse trash ou déjantée. Il s’agit plutôt de repérer le redoublement filmique mené par Harmony Korine d’un réel le plus souvent effarant, sans que sa mise en scène ne tombe néanmoins dans un mimétisme plat ni une sorte de magma pop…

La solution plastique trouvée par Korine consiste à la fois à rendre sensibles les comportements vulgaires de ses protagonistes et à révéler, sans ostentation, le monde atone qui les soutient. Sans cette dimension critique qui s’affirme presque imperceptiblement, le défoulement apparent de Spring Breakers tournerait à la téléréalité. (74).

–Ekin Erkan

Works Cited

Baudrillard, Jean, et al. The Conspiracy of Art: Manifestos, Interviews, Essays. Semiotext(e), 2005.

Baudrillard, Jean, and Sheila Faria. Glaser. Simulacra and Simulation. The University of Michigan Press, 2014.

Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx. Taylor and Francis, 2012.

Elseasser, Thomas. “Media Archaeology as the Poetics of Obsolescence.” At the Borders of (Film) History: Temporality, Archaeology, Theories: FilmForum 2014: 21. International Film Studies Conference: University of Udine, Forum, pp. 103–117.

Foster, Hal. First Pop Age: Painting and Subjectivity in the Art of Hamilton, Lichtenstein, Warhol. Princeton University PRES, 2011.

Korine, Harmony, and Eric Kohn. Harmony Korine: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Laruelle, François, and Robin Mackay. The Concept of Non Photography. Urbanomic, 2012.

Zabunyan, Dork. “De La Vulgarité.” Cahiers Du Cinéma , vol. 692, Sept. 2013, pp. 74–78.