Robin Hartman and Kim Margaret Watling, the curators of “Because I Said So… ” at the Kennedy Heights Arts Center, neatly state the exhibition’s thesis:

“Because I Said So…” (is) an exhibition encompassing the range of experiences that occur when growing up with parents or parental figures.

Everyone has a story about their parents; good, bad, funny, or sad… Personal stories reveal universal truths.

In the exhibition relationships between parent and child(ren) are expressed in some pretty basic ways: parent with offspring, parent as a child or adult, or the kid(s) alone.

Paula Cordes highlights the relationship between parent and child in Thanksgiving Traditions.The scene in the yard of the house in rural Ohio where her dad grew up is likely taken from a faded color photo. It shows him with one of his three sons. Paula’s brother holds a shotgun in the crook of his arm, ready to start out on their annual Thanksgiving hunting foray. 1Grandma looks out of the porch door with what may be a mix of nostalgia and thanksgiving at seeing her son coming home with his own children.

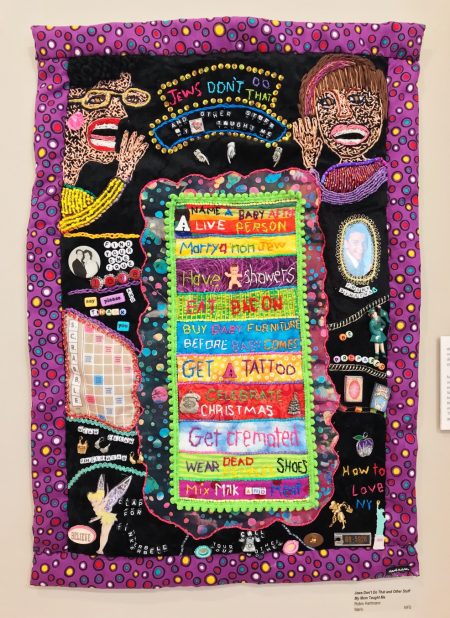

Born in New York City and educated at the Pratt Institute, Robin Hartmann worked with the Muppets for five years and as a toy designer for Kenner Toys. Her pieced fabric works are whimsical but also incisive. Jews Don’t Do That and Other Stuff My Mom Taught Meis a comic interpretation of what she learned at her mother’s knee. In the upper left-hand corner, Mom shouts to make herself heard; in the other corner, Robin cups her ear to catch everything. Some of the “rules,” or what she calls “superstitions handed down through generations,” are never having a baby shower or buying furniture until the child arrives, and that child should never be named after a living person. And, by the way, never marry a non-Jew. Other prohibitions include never getting a tattoo, never eating bacon or mixing milk with meat, or celebrating Christmas although the artist remembers always spending Christmas Eve with an Italian family, “as long as we didn’t have a tree it was ok.” It’s a humorous take on the serious topic of heritage.

The Kennedy Heights Art Center is located in an old house, and there’s been no effort to disguise that. So it’s logical to find a portrait holding pride of place above the fireplace: Gwen Davis’s Big Daddy. She painted it 25 years ago, working from a photograph in the school newspaper where her father taught industrial arts.He’s shown mustachioed and with longish hair, so the original photo might have been taken in the ’70s. He stands perpendicular to the picture plane but has turned his head to confront the viewer. His mouth is on the edge of a frown, his brows knit together. He seems to be scowling, as if annoyed to have his class interrupted. But Davis says he was mugging for the camera. I guess that illustrates one of his sayings: “… things are often opposite of what you think… ”

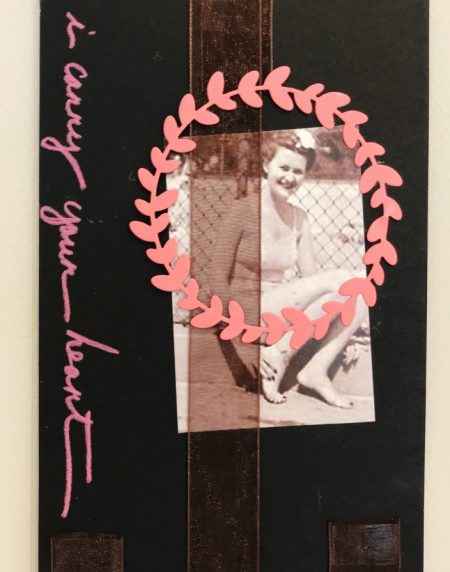

Mindy Burger’s I Carry Your Heartshows her mother as a person not defined by her role as mother. After her death, Burger found these black-and-white snaps of her posing in a bathing suit; they were taken over the course of her life, from 15 to 82. In the earliest she wears a cape like “wonder girl,” as Mindy describes her. In the last, she poses coyly, with her body hidden by a large straw hat. The artist has mounted the portraits on black cards, like the pages of an old photo album, and joined them together vertically with ribbon. Each image is surrounded by a wreath, saluting the heroic in her mom. Mindy sees her mother in these informal portraits as “unabashedly herself, embracing her body and sexuality at every age. Tumbling through life on her Jacob’s ladder, her eyes smile, and the spirit remains the same. Meet Milly Farasey: I carry her heart.”

In At the Statesman, Linda Franklin records her aged father settled into an armchair, his hands resting on his thighs. Tight-lipped, his gaze is vague. Behind him on the bare wall is a “formal” photograph of what I take to be her parents, surrounded by their grown children and, possibly, their spouses; oddly there are no children present. That photo bridges the gap between past and present.

Meili Corbin wants to capture “ephemeral memories” using graphite, a deliberately “slow medium.” It allows Corbin to stretch out the moment, to relive and ponder it. She wants to catch:

… the transitory nature of being young and the playful spontaneity that comes with childhood… the act of memory becomes an integral part of motherhood as children pass through the various stages of childhood so very quickly that some memories become a blur.

In Gaze, Corbin represents this blur quite clearly with the distorted view of her two kids pressed up against the rippled glass of a door.

In Always Be a Lady,Mary Barr Rhodes shares her mother’s code of conduct, but it’s not spelled out as blatantly as Hartmann’s childhood admonitions.You need to read Rhodes’ text on the wall label about how to be lady as it is not directly communicated in her enchanting sculpture of a virginal-white communion dress that “floats” above the pedestal.

Mary’s mother’s dictum to her tomboy daughter came without a guidebook. She had to learn from observing her mother and absorbing her reprimands as life lessons. Ladies never sit like a man, and she was admonished to cross her legs at her knees or ankles (I always heard ankles). Mary also needed to be well groomed at all times, bathing daily, and always keeping her hair brushed and tidy. And ladies never swore.

But her mother also counseled her daughter to “Be loyal to your family and friends,” “Always be kind to others,” and “ Always be in service to others.”

To exemplify these virtues sculpturally, Rhodes stiffened a communion dress with resin and presented it on a stand. Although there is no body, it still looks as if worn. The artist explains that she “didn’t include a female figure because the authentic self was not part of the messaging in the ’50s.” (Rhodes is not the only artist who has used empty garments to represent the figure. In the ’80s, Muriel Castanis employed a similar technique, draping epoxy-soaked cloth over foam mannequins that were removed after the cloth hardened. Currently Karen LaMonte casts glass to achieve the same effect.)

Instead of showing his mother, Samuel Jones lets her garden be her stand-in. Each year he and his siblings hated the drudgery of planting and weeding a garden that rarely met expectations. But in this painting, his mother’s gardenis a riot of blooms, each petal lusciously rendered in thick impasto. It’s “in remembrance of the few years when the garden looked pretty darned good,” he recalls.

I can’t believe I’m saying this, but the exhibition seems to have something for everyone, formally in approach to subject, medium, handling, style, etc. And we can all relate to being a part of a family. If you can’t find yourself in one of these artworks, you must be an alien whose existence owes nothing to anyone or anything.

–Karen S. Chambers

“Because I Said So… ,” Kennedy Heights Arts Center, 6546 Montgomery Rd., Cincinnati, OH 45213; 513-631-4278, www.kennedyarts.org. Through June 8, 2019

1 Cordes remembers that “on one such excursion he asked a farmer friend for permission to hunt on his land. After hiking for some hours, with no prey in sight, he spotted a rabbit in the farmer’s yard. He took aim and proudly presented his prize to the farmer’s wife. She exclaimed with horror, ‘My Lord, Donald, you’ve killed Chester, my pet rabbit.’”