It was 1957 when “nudity for nudity’s sake” in cinema became a point for deliberation: the court case, Excelsior Pictures v. New York Board of Regents, hinged whether the display of onscreen nudity in Garden of Eden (dir. Max Nosseck), a “ludicrous nudist colony picture,” was legally obscene. Garden of Eden was distributed by Excelsior Pictures, a New York-based exploitation outfit that specialized in burlesque short subjects. Judge Charles Desmond’s adjudication found in favor of the exploitation distributing, ruling that “There is nothing sexy or suggestive…nudists are shown as wholesome, happy people in family groups practicing their sincere but misguided theory that clothing…is deleterious to mental health” (Lewis 2000, 199-200).

Desmond’s decree provided the impetus for a significant cultural epoch of “exploitation” and, subsequently, “sexploitation” films, paving the roads for the “raincoat crowd” of 1970s’ Times Square – the peep shows and grindhouses where Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader’s lone taxi-ranger Travis Bickle (Robert DiNiro in Taxi Driver) frequented. Doris Wishman, one of the conspicuous sole female directors of the “sexploitation” period (and quite possibly John Waters’ most obvious aesthetic and thematic influence), was not was not only an integral hand in this underbelly of a midtown Manhattan long displaced by Disney-saccharine corporate visual candy and tourism traps but also belongs to the lesser known zeitgeist immediately preceding it.

Wishman’s films are often separated into three main intervals – first came the “nudie cuties,” or nudist camp films, which blossomed in the 1950s and early 60s. These prurient, harmless films featured largely topless women mischievously bedaubed in narratives as bare as their flesh; cheap, silly, and technically clunky, these films include her science fiction feature Nude on the Moon (1961), which was banned after the New York State Censorship Board ruled that while films featuring nudity in a nudist colony were permissible, the fantasy film setting of a nudist colony on the Moon was unallowable. Wishman’s second period is discerned by her engagement with the “roughies” genre – a feral, grimier moment that featured films where women were routinely beaten or sexually assaulted, such as The Sex Perils of Paulette (1965) and Bad Girls Go To Hell (1965), the feature recently screened at the Metrograph in conjunction with the reissue of video artist and filmmaker Peggy Ahwesh’s zine “The Films of Doris Wishman.” In conjunction with Brooklyn’s Light Industry, Metrograph bracketed Wishman’s film, in its original 35mm form, with the more overtly “liberating and liberated” The Deadman (1989), Awesh and Keith Sanborn’s titillating 16mm adaptation of Georges Bataille’s Le Mort (1967). While Wishman’s tertiary period found her directing hardcore pornography, it is during this second period that I would like to waver and examine Bad Girls go to Hell while contesting some of the more immediate readings that come to mind.

The film follows Meg Kelton (Gigi Darlene) after her husband, Ted, goes to work on a Saturday despite her series of protests – she pleads for her husband to abstain so that the two may spend the day blissfully detached from the outside world and Ted’s pressing responsibilities. Meg potters around her apartment in a gossamer nightgown, taking care of chores that mostly include cleaning. Upon taking the trash out, Meg is confronted by a simpering debauched janitor who rapes her on the stairwell – she quickly dispatches him, in an act of bloody vengeance, before fleeing from Boston as a fugitive. Meg adopts a seedy cinematic pseudonym dripping in self-awareness, “Ellen Green from Chicago,” and takes a Greyhound bus to New York.

Here, she confronts several male encounters – first, a mercurial nightshift worker named Ed who reticently allows Meg to stay with him in exchange for housekeeping duties only to thrash her soon, thereafter. His motivation? Ostensibly injudicious and aberrant – Meg has simply tabled a decorous dinner for the pair after abandoning the flirtatious trifling that colored their earlier interactions and seemingly inflamed Ed the mercurial chauvinist. Yet, upon recouping a bottle of cooking sherry from under the sink, Ed vigorously belts Meg/Ellen – it would appear that Ed is a recovering alcoholic and it takes only a few drinks to rile his staid composition.

As Ed’s stuporous state slips into a torpor, Ellen faintly slips out of his oriental-furnished gaudy downtown apartment. Traumatized, she befriends a deferential, jaunty and unnamed peeress who introduces Ellen to her sister, Della. Most serendipitously, Della happens to be seeking a roommate – the film’s narrative is threadbare, which proffers a brazenly self-conscious fever dream of a concoction. Della, a pin-up blonde, spends her days traversing the apartment in a black-laced fully body-stocking while intimating Meg to divulge the source of her marked sorrows. The two begin a romantic affair, hesitant at first on Meg’s part, though eventually the pair are shown making love – it is noteworthy that the sole consensual and pleasant sexual encounter during Meg’s New York scurries is a lesbian affair. Nonetheless, this fateful amour only motivates Meg to flee once more, roseate and heart-stricken. Meg and company’s motivations are always tenuous at best, thus it is best not to closely probe them – after all, upon relieving expectations of narrative plenum, Bad Girls Go To Hell ripens as a uniquely charming dreamland jubilation.

Thereafter, Meg rents from a seemingly docile uptown married couple at a rate of twenty dollars per week. The following morning, after the wife goes to work, transpires in the first lone encounter between and Meg the husband, who sexually assaults her – Meg is on the road, once more. Meg eventually finds an “invalid” (read: disabled) older woman to rent from in exchange for housekeeping and attentive care. After retrieving the woman’s medication, a scene that makes tactful use of a haptic, dislocated camera-frenzy to reveal her growing paranoia, Meg is stupefied by the grand reveal: the elderly woman’s son is a detective on the very murder case in question and has come to visit. Naturally, in philippic reproach, he both recognizes and captures Meg.

The film is then conclusively upskirted, revealing that Meg’s lengthy, malady-ridden transit has been a protracted dream sequence. Meg awakes with a shriek, as Ted re-enters the apartment to retrieve some forgotten files for his Saturday meeting (it has apparently only been a mere few minutes since he left). Meg pleads once more, galvanized by this dream sequence, for Ted to stay but Ted reassures her that the pair will have a lovely evening once his work is finished. Too browbeat to return to slumber, Meg repeats her dream-sequence actions of cleaning, though perhaps they are now rendered cathartic ablution from her frenzied nightmare. Upon discarding the trash, misfortune expatiates, this time in the waking world: the grimacing, lascivious janitor pounces. Meg’s phantasm is ratified. Fin.

The Metrograph audience guffawed at the materialization of Meg’s paranoia, drowning the meditative musings to be gleaned in this conclusion (which I find to be the most interesting facet of Bad Girls Go To Hell). However, before I implore my own analysis, let me attempt to color the film’s historical and contextual backdrop. With the exception of Satan Was a Lady (1975), a pornographic film starring sex-positive feminist and sex worker Annie Sprinkle, Wishman’s oeuvre is devoid of any direct feminist affinity or agnate consanguinity – as Peggy Ahwesh noted in her post-screening commentary, Wishman eschewed the feminist label.

Despite the now-widespread streaming acquisition of grindhouse, exploitation, and sexploitation relics by channels such as Exploitation.tv and The Grindhouse Channel, the works of filmmakers such as Wishman, Barry Mahon, Joe Scarno, and Harry Novak were originally distributed via bootlegged VHS tapes or designated for the corners and backrooms of video stores such as Kim’s Video Tapes. Mike Vraney, a Seattle-based video distributor, bought many of the sexploitation film prints and catalogued them in the 1990s, releasing them on VHS via Something Weird Tapes. We know exactly what kind of audience attended and engaged with these films during the time of their release – Times Square’s “raincoat crowd” that, as Adam Simon wrote in a 1990 New York Times article, had “very specific reasons for going to the movies…”

Avant-garde filmmakers such as Ahwesh and M. M. Serra have prompted a rediscovery of Wishman, asking questions that inquire as to the milieu and cultural conditions that gave rise to such films, while simultaneously invested in the formal architecture of the erotic spectacle and Wishman’s baroque premises and gimmicks (Gorfinkel 2017, 20). Elena Gorfinkel’s Lewd Looks: American Sexploitation in the 1960s analyzes the “roughies” in lieu of rising interest in feminist discourses on female sexual desires and agency, examining alternative sexual practices in the continuation of the “roughie” form with films that dealt with female desire, agency, and forms of sexual “deviance” in conjunction with blossoming liberatory sexual attitudes. Such is the case with Bad Girls, as lesbianism and masochism comprise the sex exposé variants of Meg’s hypnagogic ventures. While questions of intent are certainly interesting – given the consequent climate of 1970s film theory and its penchant for the symbolic, stilted in Christian Metz and Laura Mulvey’s post-Lacanian critiques – we should simultaneously qualify Wishman’s films socio-historically. By situating Wishman’s films genealogically, we can also empower analysis insofar as it frames the modernized female nude mapped within a history of libidinous spectatorship.

Michael J. Brown’s doctoral thesis, The Art of Insignificance: Doris Wishman and the Cinema of Least Resistance, poses that despite Wishman’s “nudie-cuties,” which policed their own boundaries, contained no full-frontal nudity or particularly sexual situations (by today’s standards), audiences were granted the unique exception to “look voyeuristically,” hereby thwarting an injunction against converting desire into contact by justifying desire for desire’s sake. (Brown 2015, 154). While this may not accurately describe all of Wishman’s “roughies,” it is the case that Bad Girls does not feature any explicit nudity, either – we could make the similar claim that it “policies its own boundaries,” liberating (sadomasochistic) desire. However, spectatorship and “desire for desire’s sake” are not neatly cleavage – nor are they explicitly constrained to the moving image. Rather, both belong to the variegated discursive history of a multifrontal visual culture that has, at times compulsively, produced, circulated, and consumed the female nude.

Naturally, theory has closely followed. In The Nude: a Study of Ideal Art (1956), art historian Kenneth Clark describes the contours of the nude human body as explicitly directed – the “head, left arm and weight-bearing leg form a line as firm as the shaft of a temple” (1956, 79). Anthropologist Mary Douglas, in Purity and Danger, underscores that the orifices of the body symbolize “its especially vulnerable points,” whereby spittle, blood, milk, urine, feces, tears, and ejaculate traverse the body’s boundaries; Douglas remarks that any “structure of ideas is vulnerable at its margins” (1966, 121). Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting (1987) audits the discourse of the frame – the book concerns itself with verisimilitude and the parergon (ornament/embellishment) by way of Kant’s Critique of Judgment.

Here, Derrida divests how Kant’s “criterion for exclusion” – a central tenant of Kant’s aesthetic theory of purity – and delineated “inside/outside” criterion can be problematized as a purely conditional formality (64). For Derrida’s formulation, the “supplement” both adds to and completes an entity that is already assumed to be whole, whereas for Kant it is solely depreciatory; as such, Derrida’s “logic of the supplement” (also referred to as grammatology) underscores the absence within a sense of full presence or wholeness (1966, 351–70). One of the most interesting examples of this in is Cranach’s the Elder’s 1533 painting of Lucretia, whereby Derrida catechizes “where does a parergon begin and end?” noting the transparent veil that forms a bricolage with Lucretia’s body, the dagger that subtends her hoary skin, and the painting’s (“external”) frame, which leads astray the “pure object of taste” (57, 64).

What does the “logic of the supplement” mean for cinema? Thomas Elsaesser poses that “the big screen has become, in economic terms, the supplement of the cinematic institution as a whole, yet without this supplement the rest would disintegrate around its absence” (2013, 218). Subsequently follows the relationship between the first release of a film and the chain of subsidiary markets – for Wishman’s work, this chain has always explicitly libidinally charged. However, is contemporaneous spectatorship (quite literally reducing what was intended to be erotic into something academic), removed from these epochal and immediate corporal pleasures, an “objective, pedagogical, or distanced” discernment, bedaubed in relocation and removal (168)? Or are matters more tangled and inextricable, with libidinal or hallucinogenic intensification, albeit furtively buried, reappearing within our normally humdrum and familiar surroundings? Can the female nude be a reflection or illustration of the real, rather than as an object of art, science, study, and commodity? If so, is this truly “problematic,” as the crudest of feminist art scholars would have us believe?

What Derrida, Clark, and Douglas impugn in unison is the autonomized or secularized betoken body of the female nude, descrying what Maurice Blanchot, in a text on Marguerite Duras’s La Maladie de la mort (1986), called the “excess which comes with the feminine” and the “indefinable power of the feminine over what seeks to be, or sees itself as, alien to it” (53). Rather than misattributing a consciously feminist political vigor to Wishman’s films – and in opposition to some of the more established Metzian perspectives (constricted to the grand theories of seventies film studies) – I would like to offer this lens as a meaningful way to locate Wishman’s films.

According to Tristan Garcia the “limen” is tertiary, much like Derrida’s “logic of the supplement,” as it is a “threshold or limit between two spaces, but which forms an intermediary space on its own, since every limit is a third thing between two objects” (Garcia 2014, 396). According to French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep, in The Rites of Passage, a “limen” is not simply a space similar to the spaces that it separates, however. Rather, a “limen” is a space where one’s passing also provides the means to understanding “passage” as a human metaphor of the division of time and its transformation into a spatial division projected onto the social field. In The Forest of Symbols Victor Turner notes that in every liminal stage or transitional state the individual is “betwixt and between,” that is, “between” and caught in the interval.

Meg is consistently caught in such states of liminality – throughout the film she is jittery and motile, whether traveling by Greyhound from Boston to New York, traversing the New York streets, pattering in various apartments, or anxiously cleaning, she is in a state of perpetual transition. Transition – the anthesis of escape, frames Meg’s livelihood, ever so exacerbated by the dream-reveal. As Elena Gorfinkel notes, “[t]he absurdist logic of the dream sequence only serves to reinforce the futility of any attempt to escape…akin to the looping, reflexive structures and grim paradigms of an existentialist modernism on evidence in Bergman’s Persona (1966)” (151). Both Meg’s dreamscape travels and her ignis fatuus of fugitive escape are bondaged by imaginal space.

Meg’s body is also caught in an impasse of liminality – not only in its geographic flux but, also, in how it recovers from trauma and containment/imprisonment by lapsing from the imaginary into the real. Lynda Nead, in The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, canvasses the representation of the female body in western art since antiquity, with an interest in these transitional states – how the female nude has traversed from a cultural commodity, formalized and conventionalized, to the margins and edges of categorization. Contemplating the construction of the nude’s symbolic meaning, Nead interrogates the principal goals of its aesthetic stasis by genealogically tracing the containment and regulation of the sexual female body. Accordingly, Neal offers that “the forms, conventions and poses of art have worked metaphorically to shore up the female body – to seal orifices and to prevent marginal matter from transgressing the boundary dividing the inside of the body and the outside, the self from the space of the other” (1992, 6).

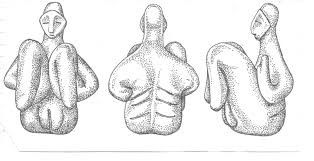

If every fold is pockmarked with pores and openings, for cyclic breaches of sensation to occur, then these orifices “make possible a sensation of the same through kinetic difference” (Nail, 97). Pores, like wounds or knotholes embedded in the body, further expose this aforementioned relationship between outside/inside (or exterior/interior, parergon/ergon), making “possible differences in both quality and quantity” (Nail 2019, 97). In Bad Girls, Meg often folds her arms and hands over her face and body, in half-fetal form – her body becomes a site for enclosing. If containment and opening, surface and the orifice, internalization and spatialization, are held in dialectic opposition, then the Venus appears once more – not solely as in Manet’s prostituted, besmirched Olympia but, also, as the maternal Venus of mythographic description. Sociologist and literary critic Lewis Mumford wrote that “[i]n line with this, the more primitive structures— houses, rooms, tombs— are usually round ones: like the original bowl described in Greek myth, which was modeled on Aphrodite’s breast.” (1961, 13). Thomas Nail details the Greek myth of Aphrodite as modeled on the Neolithic one of the Great Mother, as described by Venus figurines – the nexus of containment. Venus, with her small arms and legs, enfolded close to her body, has limbs “less for movement than for enclosing” (2018, 168).

In European Cinema and Continental Philosophy, Thomas Elsaesser describes Lars von Trier’s Antichrist in lieu of the “powers of horror” inherent in abjection – “[t]t ends with the triumph (‘chaos reigns’) of the abject: taking over in the struggle for bare life and physical survival” (150). This not only allows us to make sense of Wishman’s conclusion in Bad Girls – whereby “chaos reigns” and her violent nightmare/paranoia is evinced – but, also, provides us with a means to qualify how Meg is rendered to the conditions of bare life. Throughout the films, her ventures are reduced to homo sacer, or mere survival – however, abjection is not the same as victimization. Rather, such conditions unambiguously release the protagonist from the victim status and make her visible as an abject, “since the abject…is someone who first must be case out before becoming visible” (154). Cast out by Chicago, the law, and a multiplicity of New York City apartments, it is only through her abject subject-position that Meg becomes politically visible, suspended between “the power that accrues from ‘wanting nothing’ and the power that derives from ‘having nothing (more) to lose’” (159).

Recall Plato’s Phaedo, where Socrates’ disciples, present at his death, could not help but laugh – “Simmias laughed and said, Upon my word, Socrates, you have made me laugh, though I was not at all in the mood for it.” (64:b). It is irony and humor that invigorate the essential forms through which we apprehend the law. In his biography of Franz Kafka, eponymously titled Franz Kafka, (1937) Max Brod recalled that in Kafka’s public reading of The Trial, everyone present, including Kafka himself, were overcome by laughter. This dark laughter, as mysterious, inexplicable, and invigorating a phenomenon as the laughter greeting Socrates’ death, belies whatever false precedence of satire and repartee contemporary audiences may profess to view Wishmans’s “roughies” with. This is, however a pharamakos and not to be bridled by the sort of identity politics policing stifling the contemporary left. Thus, in response to Elena Gorfinkel’s question “[w]hat kind of audience attended and engaged with these simultaneously excessive and rhetorically complex films?” (20) I bid the perhaps unfavorable response: an audience not too far removed from today’s gallery-going banter-bled cinephiles, though they will not admit it. It is, quite possibly, the laughter of the masses that both silences Meg’s scream and allows it to resound.

–Ekin Erkan