“She has an interesting eye… but it’s wildly different than anything I would hang in my house.” I overheard a woman say that to her friend in “Order of Imagination,” a moving retrospective of Olivia Parker’s forty-plus years of photo-making at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA. Maybe I’ve followed one too many collage artists on Instagram, but I can picture most of these hard-edged still lifes at home in kitchens and hotel lobbies across America—and write down today’s date, because this is probably the only time I will mean that as a compliment. These breathtakingly painterly photos seek not to shock, but to saturate—to shift the familiar to a new plane. Clothe my walls in it.

What makes this retrospective especially powerful is the lead-up to the final gallery, which contains an emotional, but not sentimental, dive into her late husband’s battle with Alzheimer’s Disease. The journey through this exhibit makes it well worth a visit; it closes on November 11, 2019.

Parker, a Boston native who has lived in Manchester on Massachusetts’ North Shore for decades, trained as a painter but switched almost exclusively to photography early in her career. Self-taught, she embraced new technologies while sticking to familiar themes in her still lifes. The fact that the style of these photos seems familiar is, perhaps, proof that she was ahead of her time in an aesthetic capacity. But I would also believe that her split-toned black and white photos, primarily from the 1970s, were created in the 1920s in some Paris garret. Her fondness for illusion, shadows, and double meanings—mostly using everyday found objects, detritus—would have held weight with the surrealists. Yet the conflict in her compositions stems from intellectual and poetic inferences, usually to do with the natural world, instead of more straightforward eroticism—perhaps because of the absence of the human figure.

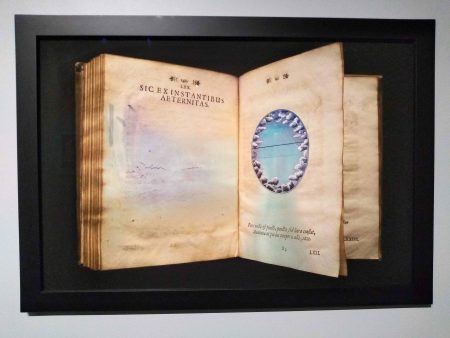

The emotional blow of this retrospective, curated by Sarah Kennel, is unassumingly woven into its progression. A first gallery features Parker’s split-toned still lifes from the 1970s. While she was not the first to experiment with split-toning, which occurs when a print is left for longer than recommended in a selenium toner bath so that black and white tones take on warm reds in some areas and cool blue-greens in others, the work in her book “Signs of Life” (1978) has been cited as one of the first deliberate explorations of the technique. Her subjects include seashells, pears, eggs, rusted detritus found on the beach—many assembled in matter-of-fact specimen boxes that would look at home in a museum drawer—deftly arranged to suggest movement, in some cases, when in fact most of her compositions were made on the floor, shot from above. She describes her work as “diagrams of the unseeable.” The almost clinical term “diagram” is the perfect word choice for her subjects, many of which would be at home in a staid natural history museum. The unseeable is what the viewer brings to her placements.

These objects are essential to the emotional impact of this retrospective, although the viewer may not realize it. What helps is that, as centerpiece of the initial gallery, we see a delightful jumble of many of the objects used in each assemblage. Parker’s practice of roaming the beach or compulsively pulling her car over to claim interesting objects is integral to her work. The objects commune in the light of an ocean view in her studio, and she sometimes keeps them for years, letting them mill around each other before committing them to a photograph.

We know this because one of three videos in the exhibition tells us so. The process-oriented videos, in accordance with Parker’s proclaimed philosophy, do not tell the viewer how to feel. Instead, they bring us closer to her—we feel a new tenderness for the dingiest of parts, and the hands that chose them.

The ensuing galleries show a departure in style when she adopted a nascent technology: Polaroid film. Large Polaroid prints engulf us in a richer color palette, like we’ve entered living collages. The same playfulness and exploration of nature continues in these larger-format Polaroid, inkjet, and gelatin prints. An “insect” phase, which occurred while renovating her home in the 1990s, stemmed from finding dead bugs in corners of the house. This period also marks a more frequent us of a macro zoom lens.

Throughout the exhibition, the viewer is tickled and astonished, generally lapped up in the loveliness of these shots. But that gut punch does come in the final gallery with her newest work, which centers on her husband John’s descent into Alzheimer’s Disease before his death in 2016. It’s easy to hear that topic and brace for sentimentality, but having journeyed through Parker’s career, we know better than to expect her to tell us what to think. What’s more, although her preceding pieces are not expressly personal or confessional, seeing her life’s work evokes a closeness between her and the viewer that makes us take John’s illness more personally, even if we have no experience with Alzheimer’s Disease. We’ve seen the objects this woman fished from the sand, transformed with shadow and alternate perspectives. Now we watch her process her husband’s illness through her art.

The shift in placard format contributes to the emotional shift; instead of the expected information about the media and process, the explanations only consist of brief quotes from Parker herself about the meaning of each piece in relation to her husband’s illness. For example, next to “Twenty-Nine T-Shirts”: “As he slipped into an unknowable world, John seemed to want more and more essential clothing.” Of the piece “Alzheimer’s Notes,” she writes: “When John was diagnosed in 2013, he ignored the bad news. He never said he had Alzheimer’s and I think the only time he wrote it down was after his neurologist asked him to make a note of it and spelled it for him.” The wild animals listed on the same piece of paper were part of another doctor-prescribed exercise, which fits neatly into a theme of an untameable turn of events.

The works in the final gallery depart in style as well, featuring usually only one or two objects and playing heavily with fractured light, evoking synapses, nerves, and an overcoming force that is impossible to hold. “Last Light” is an especially poignant example, with Parker’s conjecture of what John may have been able to as he died. The photographs became her way to hold what cannot be defined.

There is one final video after this gallery, one with no generic piano soundtrack, only the rustle of her airy studio. She leans over from her seat on a stool, shooting from above, moving her objects and colorful glass bottles to produce the desired effect. In the museum, a child gasped when the results of this process were shown on the screen in a photo that appeared incomprehensibly derived from the positioning we’d just witnessed. How quietly powerful to see this process after exhaling through the understated heartbreak of the final gallery, to see the meditation behind grief and joy-driven works alike. While Parker’s photography stands out on its own, viewing the expertly-curated retrospective at the Peabody Essex Museum adds an irreplaceable dimension to the viewing experience.