A dilemma faced by any art museum is how to keep the public consistently engaged. One way to do this is through visiting exhibitions, which are essential to the vibrancy of the museum. However, what about the permanent collection? How can a museum newly engage patrons with paintings they may have seen many times before? The Toledo Art Museum (TMA) has taken on this task with its exhibition “Everything Is Rhythm: Mid-Century Art and Music” which opened in April of last year and runs until February 23rd. Composed of 14 abstract expressionist works from TMA’s permanent collection, “Everything Is Rhythm” pairs each painting with a song to differently engage the viewer with the art.

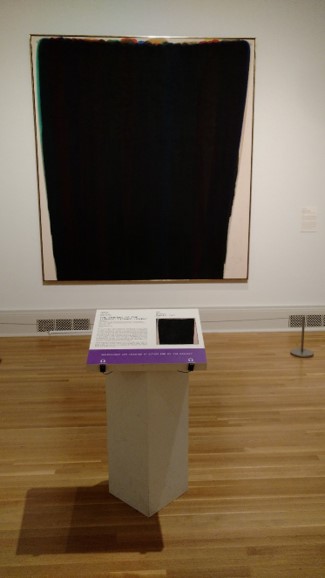

The exhibition is brilliant in terms of execution. Each painting has a small podium placed about three feet from the canvas with four headphone jacks and a short text introducing the musician and why she /he was chosen to be paired with that particular painting. The songs or song excerpts run on five minute loops, more or less. Because the viewer must stand (relatively) stationary to listen to the music, the exhibition encourages sustained attention to the paintings. Casual patrons of art sometimes struggle connecting to nonfigurative work, which is what makes Toledo’s choice of focusing on the abstract pieces in their collection particularly apt. The pleasure of abstract pieces often comes from the interplay of color and form, something that is hard to fully appreciate unless a viewer spends at least a few minutes looking at the painting.

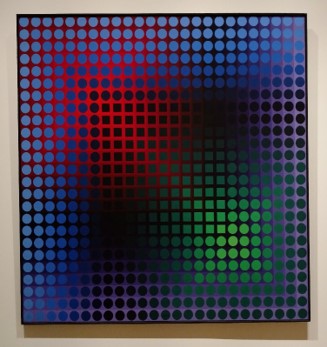

Victor Vasarely’s “Alom I,” which is paired with Tim Story’s “Cell Six” from the album The Roedelius Cells, is a great example. I’ve seen the painting a number of times but never really saw how much movement is in the work. A causal glace will be enough to notice the piece’s Op Art illusion of the upper left and lower right quadrants seeming to bulge out. What I never noticed before was the movement in the piece, the way the red background in the upper right quadrant pushes the eye towards the bright blue circles in the uppermost corner which grow lighter as the red deepens before moving with the lighter blue to the upper right corner. However, as the blue circles become more saturated, the background lightens to purple and your eye moves down the painting, and just as the purple darkens, the bright green circles command your attention and darken as they transition into squares, creating a wedge that pushes you back to the red of the upper right quadrant again. While there’s nothing particular about Story’s music that leads me to see the painting this way, the music creates a space where I am alone with the painting long enough to notice these effects.

Other pairings, however, do radically alter how the paintings are received. Hans Hofmann’s “Night Spell” is matched with Miles Davis’ “Florence Sur Les Champs-Elysées” from his soundtrack to the film Elevator to the Gallows. “Night Spell” features four glossy rectangles with sharp edges foregrounded against multiple mat rectangles that never fully form and are then covered by an opaque, almost neutral brown, which muffles the inchoate shapes beneath. Davis’ organic horn and snare draw attention to the fluid background as opposed to the fixed rectangles, which are most immediately noticeable to viewers due the warmth of their bright red, orange, purple, and green colors. Had the painting been paired with the metronymic Philip Glass (as Julian Stanczak’s “And Then There Were Three” was) the viewer would instead be drawn to the angularity and strength of the foreground. Another example comes in Ad Reinhardt’s “Number 1, 1951,” which is paired with “Sonata No. 5” from John Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano. When viewed with the watery, accidental quality of Cage’s prepared piano playing in the background, the long rectangles look less like rectangles and more like the extended brush strokes they are. As the music moves and the viewer stares longer at the painting, the black background seemingly brushes against the rectangles, eroding and threatening to subsume them, making its absence of color a presence, the same way Cage’s work makes “silence” a heard presence.

Further, the music can be additive. As opposed to focusing the viewer’s attention on a particular aspect of the work, the music can actually create an additional layer to the painting. I saw this in Morris Louis’s “Dalet Tet,” which was matched with an excerpt from Gavin Bryar’s The Sinking of the Titanic. “Dalet Tet,” has always been an evocative painting for me. Morris’ long thin pours of color, obscured by the purplish black “veil” evokes a sense of loss. However, the loss “Dalet Tet,” draws out is allusive. Perhaps this is why it works so well with Bryar’s The Sinking of the Titanic. To begin, the two pieces share the same compositional technique. Like “Dalet Tet,” The Sinking of the Titanic consists of multiple layers. A slowed down version of the hymn “Autumn” (the song the band was believed to have been playing as the Titanic sank) forms the base of the song. Integrated into this are recordings of interviews with survivors and a wavering second set or orchestration, dominated by an oboe. This second set of orchestration obscures the “Autumn” at the base of the song, much like the veil of dark paint obscures the bright colors in “Dalet Tet.” However, Byar’s piece expands the scope of the painting by connecting it with an actual tragedy. While the watery quality of the music helps draw out the fluidity of Morris’s painting, the most important thing The Sinking of the Titanic adds to the piece is to put something at stake. Now, the loss “Dalet Tet” evokes is material. Of course, viewers will not necessarily have a personal or cultural stake in the loss of the Titanic per se, but by grounding the feeling of loss evoked by the painting in something real (and this is accentuated further by the inclusion of interviews in Byar’s piece—which, unfortunately aren’t part of the excerpt used in the exhibit), viewers are given more license to connect the piece to a material loss. The addition of a memorial to the Titanic invites viewers to ground the piece in a specific lived experience.

The main reason I find this exhibition so interesting is it’s an opportunity to see the work of the curator explicitly. The work of curation, as I often see it expressed in museums, is to “correctly” group works of art into their proper artistic movement, chronological order, medium, country of origin, etc… While this is an interpretive task, it’s not the same as the interpretive work that is being done in “Everything Is Rhythm.” The work of pairing each painting with a song provides me with new and unexpected viewings of each.

I once had a film professor tell me that heavy use music in movies was a cheat since music can work as a short cut to the emotions the film itself should produce. And, I could see the same criticism being levied against this exhibition. Further, critics could argue that the artists did not make these paintings to be displayed with music. Therefore, including music with these painting robs the artist of her/his intention. However, neither of these are fair concerns to me. In my opinion, displaying art by these standards actually robs the viewer of the museum going experience. If all a curator does is display art in a “correct” order with a summary of the artist’s intent (as stated by the artist), she/he is not providing a service beyond what could be found on the internet. By creating these new contexts, the curator opens up new possible dialogues (as whole papers could be written on what songs pair with what paintings, and how each changes the other). In short, “Everything Is Rhythm,” creates new spaces for viewers. This, to me, is the most essential role a museum plays.

“Everything Is Rhythm,” is just one of the many superior exhibitions currently at the Toledo Art Museum. Other, concurrent exhibitions include “Global Conversations, Art in Dialogue,” which runs until April 26th, Yayoi Kusama’s “Fireflies on the Water,” which runs until April 26th as well, and “Expanded Views’ Native American Art in Focus,” which runs until December 6, 2020. The TMA is open Tuesday & Wednesday, 10am-4pm, Thursday & Friday, 10am-9pm, Saturday 10am-5pm, Sunday, Noon-5pm, and closed Mondays. Admission to the museum (and “Everything is Rhythm”) is free, but selected exhibitions do require an admission fee.

Matt McBride is an instructor at Wilson College where he teaches in the English Department and in the interdisciplinary MFA program. He holds a BFA in poetry from Bowling Green State University and a PhD in English & Comparative Literature from the University of Cincinnati. His first book of poems, City of Incandescent Light, was released by Black Lawrence Press in 2018. He can be found online at mattmcbridepoetry.com.