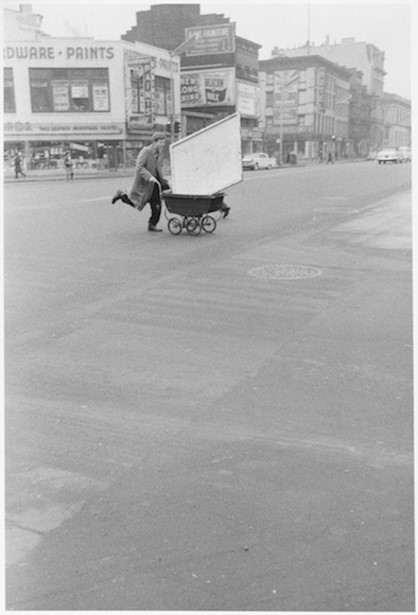

“Red Grooms Crossing Third Avenue”, 1959,

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs

New York City in the 1950s and early ’60s was alive with art and music. The Abstract Expressionists were painting, the Beats were writing and reading poetry, performance art was taking off, jazz was everywhere and what would be called folk music was also being heard. Robert Frank was in his ‘30s making photographs, then films. His next-door neighbor on Third Avenue (near 19th) was a young photographer, still in his 20’s, named John Cohen. In 1958 Cohen became the stills photographer for Frank’s first film, Pull My Daisy (with Allan Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac’s narration). I’ve heard that many of the New York photographers would often gather at Cohen’s loft, in part on the chance that Frank would drop by. When an unknown Bob Dylan arrived from Minnesota in 1962, he came by too. Cohen photographed the fresh faced Dylan in his loft and on his roof, and reputedly taught him old-time guitar styles. What’s a photographer doing teaching Bob Dylan guitar, you may ask? Well, let me tell you some about John Cohen.

Born in 1932 in Queens, NY and moving at the age of nine to the Long Island suburbs, John Cohen remembers his parents practicing “some kind of international folk dancing” but it wasn’t until he was 16 at a summer camp in the Catskills that he heard Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads and was first exposed to the marriage of music and social causes, songs describing an America he had not even known existed; “I found this music opened up a huge world to me.”

“Woody Guthrie at Cooper Union”, 1959,

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs

Cohen began photographing in 1954 while a student at Yale, recording the downtown New York art world in the cafes and coffeehouses. But he also travelled to Appalachia and the Andes, photographing traditional musicians and weavers. In 1958, the year he worked on Frank’s film – eventually expanding his interests to include film – he also expanded his interest in music by forming an old-time string band, The New Lost City Ramblers, with a friend from Yale, Tom Paley, and Mike Seeger, half-brother of the great Pete Seeger (who’d been blacklisted for much of the 50’s). The Ramblers helped usher in the popular folk revival of the 1960s, introducing the North East to the music of southern Appalachia through their own playing of the music, as well as publishing John’s field recordings (the album covers for which John designed, becoming a template for future old time and bluegrass record covers) and staging live concerts by the original musicians. Cohen travelled (often by bus) to Appalachia to record (and later film) musicians there with a bulky, spring-loaded tape recorder, initially so as to learn how to play and sing the music as authentically as possible. One of Cohen’s location recordings of the music he encountered in Appalachia and in the Andes – a recording of a young girl in the Peruvian altiplano singing a Quechua huayno, a wedding song – was included on the Golden Record on the Voyager space probes, representing the peoples of the Earth to the rest of the cosmos, even now traveling through interstellar space.

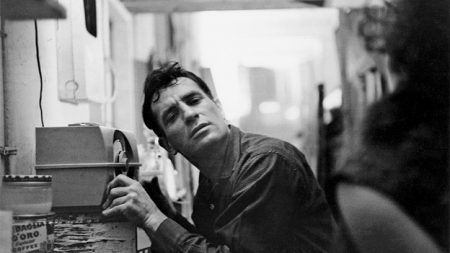

“Jack Kerouac listening to himself on the radio”, NYC, 1959

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs/Getty

I first encountered Cohen’s photographs through those he made in Peru, published in Aperture and Creative Camera in 1972. The portfolio in Creative Camera particularly affected me because I had a portfolio of my own photography in the same issue. Whenever I’d show it to someone, they’d inevitably peruse the entire issue and slow down at the Cohen pictures. I’d get to see them again and again, usually over someone’s shoulder. They captivated me. It’s the only other time viewing still photographs that I thought I could hear the pictures (the first was as a boy, standing in front of a Karsh photograph of cellist Pablo Casals, rehearsing alone). There was music in these pictures, pictures which not only caused me to travel to Peru myself four years later but to curate three exhibitions of Cohen’s work, in three countries, over three decades. The Creative Camera portfolio was accompanied by this lone text, a sketched bio of just a dozen sentences, stacked vertically and centered. It made my head spin.

Born in New York City, 1932.

Bachelor of Fine Arts, 1955, Master of Fine Arts, 1957, Yale School of Fine Arts.

Studied painting with Joseph Albers, photography with Herbert Matter.

Masters thesis on weaving in Peru.

As freelance photographer, photographs appeared in Life, Time, Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Times.

Exhibitions at Limelight Gallery, Image Gallery, Yale University Museum, AICA.

As a filmmaker made The High Lonesome Sound, 1962, and the End of an Old Song, 1969

In 1958 organized The New Lost City Ramblers, a musical group playing old time music, and performs with them continuously.

Recorded and produced collections of folk music for Folkways Records, including Mountain Music of Peru.

Taught Photography, Film Making and Design at Silvermine College, 1968-1971

Visiting critic in Graphics, Rhode Island School of Design, 1969-1971

This early list was compiled in1971; the following year Cohen started the photography program at Purchase College SUNY, where he taught for the next 25 years (also teaching drawing). “One early idea I had was to be a painter,” he explained, “but between the prospect of a life in front of an easel or photographing out in the world, photography won out. Photography could become personal, subjective, and documentary. The lens became the center of an equation with the visible world on one side and the interior world on the other”. This expressive documentary form stayed with Cohen through his filmmaking as well. The title of his first film, The High Lonesome Sound, has become synonymous with the old time music of Appalachia. Not only did his methods of reclaiming cultures through performing, recording, publishing and staging concerts by the musicians themselves help inspire the folk music revival of the early 60’s and the old time fiddle revival, they also inspired the 70’s revival of Eastern European Jewish Klezmer music. His influence extended even to people like Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead; that the Ramblers were the inspiration for the song “Uncle John’s Band” Cohen called “a true rumor.”

“Q’eros, Raymundo, Andrea, Nicholas Quispe Chura”, 1956

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs

“I’ve been called an ethnomusicologist, a visual anthropologist, a professor, a filmmaker, a musician,” Cohen once said of his wide-ranging activities (oddly not including the term “photographer”). “I think it’s the inadequacy of our language, or our need to put a label on every aspect of things. To me, I just move from one to the other.” The term Renaissance man is sometimes applied in later centuries to someone multi-accomplished in the arts; seldom has it been more apt than applied to John Cohen.

I met the man for the first time in London in 1976 when he represented the United States as the Bicentennial exchange artist (filmmaker) with Great Britain. In 1980, as the director of Yr Oriel Ffotograffeg/The Photographic Gallery in Cardiff, Wales, I finally had the opportunity to curate an exhibition of his work. Of course I chose the Peruvian photographs, and paired them with a second exhibition by the 19th century Cuzco photographer Martin Chambi. I can still remember the package address of just “Thompkins Corners, Putnam County, NY” (in the lower Hudson River valley), and John’s telling me he kept his photographs under a haystack in the barn so they’d stay dry. I’ve been privileged to do two more exhibitions of Cohen’s photography, one in Germany I titled John Cohen: Now Hear These Pictures (the work from Peru again) and one in Cincinnati, of his Appalachian work, at the Deogracias Lerma gallery on Over-the-Rhine’s Main Street.

“Roscoe Holcomb Coming Home”, Daisy, KY 1959,

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs

John Cohen made 19 documentary film in his lifetime, 25 recordings as a performer (most with the New Lost City Ramblers), and something like 16 field recordings of other musicians. His films have been shown at countless international festivals and museums, for which he has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Fulbright Fellowship and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts (Media, Folk Arts), New York State Council for the Arts, American Film Institute, Ford Foundation and numerous others. Yet it is only in this century that his photographs have received the recognition they deserve, particularly via his first monograph There Is No Eye: John Cohen Photographs (powerHouse Books, NY 2001) with its innovative, included CD There is No Eye; Music for Photographs of music to play while looking at corresponding images. These were John’s recordings of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Reverend Gary Davis, Elizabeth Cotton, Roscoe Holcomb, and others, including two lovely songs by daughter Sonya and son Rufus (both from his marriage with Peggy Seeger, the youngest member of the musical Seeger family). His photographs have been collected by the Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, National Portrait Gallery, Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum, to name but a few. His archives reside in the Library of Congress.

“Macchu Tussec dancers”, Juli, Peru, 1957

Copyright: John Cohen, Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs

I last saw John about five years ago at Iris BookCafé and Gallery in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine (a few doors up from where Lerma’s gallery had been); he’d stopped in to say hello, have some soup and see the exhibition on the walls. He was in the area to play a concert in Newport, KY, just across the river, with his latest group, The Dust Busters. “My running joke about The Dust Busters,” he’d say, “is that you take the three of them and add their ages together and I’m still older. But we play together like it was meant to be. I think that the outlook I pursued with the New Lost City Ramblers and my own work has affected a lot of young people to follow a path that they wouldn’t have followed otherwise.” No doubt there. This was shortly after Cohen made his last film, Visions of Mary Frank (2014), a largely conversational, 55-minute documentary, intended to shed light on the artwork of woman more often recognized in the 1950s and ’60s as the subject of photographers Edward Steichen, Walker Evans and Ralph Gibson, as well as the one she married, Robert Frank.

Frank and Cohen died just seven days apart last September.

“There is a saying that the treasures of the universe may be found between the eyes of a horse. One could say that the treasures of the earth may be found between the eyes of John Cohen. For we find in the images offered by this humble man, the wisdom of simplicity—its music, and its silence.” —Patti Smith

William Messer is a photographer, curator and critic based in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has written for numerous publications in a dozen countries and curated/organized more than 100 exhibition presented in nearly 40 countries. For the past decade he has curated photography exhibitions at Iris BookCafe and Gallery in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati. This October he was elected a Vice-President of l’Association International des Critiques d’Art (AICA) in Paris.