Predictably, I’ve been lamenting my inability to go out, visit museums, see films or generally have a good time in public. I often write on photography, visual art and technology but I try to avoid taking in art electronically. Aside from watching films on my TV, I generally want the intimacy of standing a few feet from a piece. Pandemic times have me reflecting on why I feel so strongly about this intimacy. In some ways intimacy with art does have to do with proximity, though I’m learning to apply skills that I’ve been using to watch films for years. I’m learning to find the intimacy at home. When Daniel asked us to write columns of our choice, I bounced back and forth between a handful of ideas but I thought that this would be a perfect time to write about film because it’s the only time I can recommend a film as an “exhibition” of sorts.

Halina Dryschka’s film “Beyond the Visible – Hilda af Klint,” – and the specific means to which it came to my attention – provides a multi-layered glimpse of what might be a new normal for some art appreciators and gallery visitors – and likely already was normal for many. If you, like me, live in Cincinnati then you’re likely familiar with Louisville’s Speed Art Museum. You, also like me, may only be able to get down there on rare occasions. As a haven of Cinema, it holds a special place for me. In my college days I had the fortune to see David Lynch’s films “Eraserhead” and “Mulholland Drive” – both of which I love dearly – projected on film. The only other place I can think of within reasonable driving distance that has the capability of showing films like those is the Wexner up in Columbus. Fortunately, due to our current disaster, we Cincinnatians do not have to drive to visit our southern neighbor, nor do we have to travel to visit a lot of great museums for that matter.

Since I’m on their email list, I received a message from them last week with the subject line #museumfromhome. The Speed (along with the Cincinnati Art Museum and plenty of others) is tapping into, and reminding us of, our need for art. When I missed my article assignment last month because Covid-19 closed the gallery I was supposed to review I was sad. We should be sad! We should also be celebrating the sheer access that we’re being given, and have in some cases already had. Before the closures I always questioned if it was worth consuming art through a screen. I’ve also always been privileged to live in a major city with a car and the money and mobility to be a gallery and theater patron. Now I’m allowing the screen to feed my cravings and, further, my excitement to eventually experience differently. Before it was a matter of better of worse, and now I’m beginning to think the difference does not have choose one of those sides. I’m becoming more grateful for art accessibility. We all should be.

The Speed’s email had some links to interactive art making and a few virtual galleries. I revisited a favorite Cartier Bresson image that’s in their collection. They recommend Bong Joon Ho’s fantastic recent film “Parasite” which is streaming on Hulu. They have links to a few exclusive films, thankfully presented by a program called “KinoNow” which Kino developed exclusively for this time in order to support Art Cinemas (their programming is nationwide so check for links on your local theater’s website. “Beyond the Visible” costs 12 dollars to rent). The Hilda af Klint film, which began streaming on April 17, makes an interesting attempt to reconfigure the history of abstract art, with af Klint as the progenitor (Ekin Erkan actually reviewed her exhibition in New York for aeqai last June). I had some interest in abstract art when I was younger but drifted from it in favor of more strictly political and cultural art. Our crisis, which in many ways is unfathomable, has pushed me back into the fold of the Abstract. What we find in the af Klint film – and abstract art – is an exploration of reality that both tries to make sense of and wallows in uncertainty. It’s a sort of blissful wallowing that has soothed my mind. The documentary presentation of af Klint can push us to think differently about how we consume art and how technological progress is changing that consumption.

Hilda af Klint, born in Sweden, worked most consistently during the first couple decades of the 1900s. Her work is a prolific exploration of the dualities of science and mysticism. She seeks to explore the invisible (hence the film’s title) – the waves, molecules and atoms that make up our surroundings. Her most interesting paintings utilize a rich, soft color palette and striking geometry. A painting of radio waves is one of her darker paintings, though it doesn’t feel imposing. It imagines waves as a circular, ordered and connected system of power. Though it is only a visual interpretation of what radio waves may look like, it’s logical in its abstraction. The waves, which we presume exist in some sort of chaos, are ordered and organized so as to be able to harness them to transfer messages and discourses. Here science wallows in fantastical imagery while ordering the waves with abstraction.

Hilda af Klint, “Radiowaves.”

Screen cap from Halina Dryschka’s “Beyond the Visible: Hilda af Klint.”

Available to rent from KinoNow. 2019.

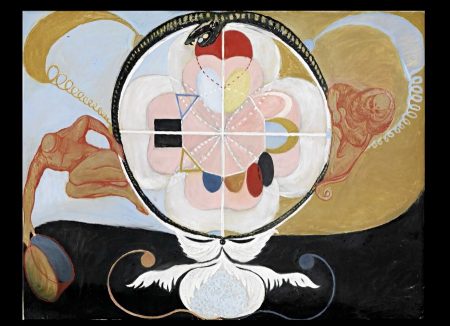

It’s not hard to find the spiritual and mystical in that scientific work. At one point a practicing medium, she used painting to understand both the temporal and the otherworldly. Some of the imagery takes on an epic, sort of Blakean, power to it. Her syntheses work to try and find order in the uncertain. One painting depicts a round form, encompassing rounded shapes and soft colors. Atop the orb sits a snake, while two men cling to either side. The painting strikes me because it is both strange and orderly. In her time, when scientific progress was exploding, she seems in this image to be aware of the human ability to abuse power. If within the orb sits the natural world, the scientific and spiritual unknown, atop sits a natural predator serving as a reminder to the inquisitors on the side not to poke the bear too hard. As a modern reader I see her taking part in human progress with an impressive, early awareness of the kind of natural destruction that humans are capable of.

Hilda af Klint. Unititled.

Screen cap from Halina Dryschka’s “Beyond the Visible: Hilda af Klint.”

Available to rent from KinoNow. 2019.

Af Klint strikes a beautiful balance. Her synthesis of the scientific and the spiritual demonstrates clear aims and desires to explore and visualize the unseen. It also makes it easy for viewers to find wonderment in that unseen. In this way, her abstractions allow us to appreciate both the order and chaos that she attempts to harness. Usually, when I write, I’m trying to coax arguments and answers out of work that I’m confident is attempting to do just that. In the time of Covid-19, I quite like the comfort and wonderment in the presence of abstraction and the unseen of Af Klint’s work. Whether it be the unseen future, the unseen state of arts and humanities communities, or the unseen state of my bank account, it’s been all too easy to sink into melancholy.

This is not to say that we should also forget about the urgent cultural issues and transformation that we’re mired in. For viewers who watch the film, they’ll find a perfect example of the ups and downs of the documentary medium. It is well made but bland in its craft. Dryschka’s staging of an actor painting as Af Klint feels both cliché and unnecessary. The film does much to argue for the wonderment of af Klint’s work (which I clearly find compelling) but works to recreate it in the least wonderful of ways. It sometimes feels like watching a tedious power point of her paintings. Often placing af Klint in contrast with Kandinsky, the film can be a little heavy handed in politicizing the place of af Klint in art history. For a documentary that makes a case for the pioneering spirit of the artist, it sometimes feeds into tiresome tropes of the documentary form.

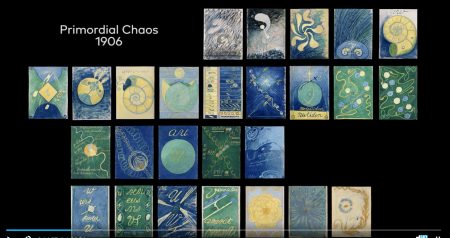

Hilda af Klint. “Primordial Chaos.” 1906.

Screen cap from Halina Dryschka’s “Beyond the Visible: Hilda af Klint.”

Available to rent from KinoNow. 2019.

These failures, though, also remind of the use of the form, which is relatively new. At its best, the documentary provides both appreciators and intellectuals alike with a myriad of possibilities in a neatly packaged 90 minutes. Af Klint was an unimaginably prolific artist who, at one point, painted 111 paintings in 1 year. As a critic, I can’t scratch the surface of that volume of work right now but the film is able to show most of the works. Though we sacrifice the choices of order and duration in which we see the paintings, I felt a wonderment of my own at being able to see the sheer magnitude of the artist’s work. The film is able to present us with a handful of informed sources to make its argument for the reconfiguring of art history. Despite my criticism, I do believe the film’s feminist reclamation of Af Klint and women artists is greatly important. It’s probably a wonder in itself that her name is now circulating, and I think that is a very good thing. The ability to present a biography, the work and theorization of the work is a testament to the use of the documentary form.

Screen cap from Halina Dryschka’s “Beyond the Visible: Hilda af Klint.”

Available to rent from KinoNow. 2019.

Though it isn’t exclusive to the Speed, in this context, the film serves nicely as an exhibit of the Speed’s “virtual museum.” During this time in which the virtual museum is the only option, I’m finding myself exercising much more empathy toward some kinds of accessibility that I was once a skeptic of. I’m reminded that though it doesn’t feel the same as stepping into a gallery and basking in the presence of a painting, I’m fortunate to ever have that choice. I’ve seen arguments that the virus is changing the way we can experience art, though I’m more inclined to think that it’s revealing the necessity of different means of experiencing art. For me, sometimes engaging with art is work, but this time has placed emphasis on it as a basic human means of understanding, coping and questioning. Though I will relish in my first opportunity to step back into a gallery, for now I will continue to shell out 12 bucks to support my valued institutions and step into galleries at home.

–Josh Beckelhimer