In the late 1980’s, visiting Chicago on the occasion of one of his exhibits at an art gallery of the city, Thom Shaw witnessed a gang fight, the members of which were wearing T shirts depicting the late Malcolm X. He found the association intriguing, Malcolm X in his mind being a promoter of unity and good relationships, not one of destructive fighting. He decided to learn more about gang life, its roots, how it reflected the problems of society, and embarked into interviewing gang members, inquiring about their life and thinking, collecting at the same time a visual repertory of their stories for his own artwork.

This opened large horizons to Shaw, not only for his visual artwork but also for his understanding of the reasons behind the many problems and violence affecting his African-American community, and, as a result, for the messages he would generate and use his art to convey.

Thom Shaw was born on August 28, 1947 in Cincinnati, Ohio. He graduated from the Art Academy of Cincinnati in 1970 and went on to become a locally and nationally well established artist. Social commentaries first appeared in his work during his senior year in college, triggered then by the prevailing civil rights movement and the Vietnam War; they did not, however, develop and expand, until many years later.

After his graduation, he worked for many years as a graphic designer for Cincinnati Bell and created, during that period, large scale, non- representational, abstract collage assemblages and color paintings, that sold very well but that did not, according to him, fill the void in his inner soul.

Around the time of his gang encounter, Shaw started instead making large woodcuts with social themes that incorporated the ills of his community; they led him to his evolving series titled the “Malcolm X Paradox”. They were exhibited in 1991 in downtown Cincinnati and were very well received, finding an immediate echo in Over-The-Rhine (OTR) dwellers who strongly identified with them. In 1994 an expanded series was also shown at the studio museum of Harlem in NY City and a year later at the Cincinnati Art Museum, in an exhibit curated then by Kristen Spangenberg, curator of prints. Through them Shaw had carved a gang icon which represented the many ills of society, the broken down family, the loneliness of youth, the addiction to drugs as an escape, the resort to violence to prove oneself. His images were very graphic, showing killings, prostitution, drug dependence… Many, especially in the African-American community, criticized them as being derogatory to the black man, as confirming the mediatic notion that the latter was a menace to society. Shaw, however, disagreed: “My images specifically depict the negative effects society imparts on African American males with whom I identify,” he once told me; “I wanted to show the black man as a victim, a target of the many societal ills; I wanted to raise awareness about his condition”.

Ahead of his time, Shaw was already decrying the profound negative effects the prevalent systemic racism in our country, and its resulting inequalities and inequities, had on the psychological, emotional, physical, economical… and safety well-being of the African-American individual and, in particular, on the balance and stability of the black family that raises him. Resorting to his powerful art he was screaming out the ills affecting the daily lives of Blacks in the United States and the heavy toll their community was paying as a result.

His “Malcolm X Paradox” series, composed of many large woodcut prints, represents the African-American young male, deprived of a strong and stable identity, robbed from him by the racial system in which he grew up, trying to assert himself differently, by joining a gang family. His natural family, in many instances being destabilized as a consequence of the prevailing systemic racism, the gang would become for him an alternate stabilizing social system, one which accepts him, protects him, and provides him with self esteem and with a reason to be. The price to pay, however, would inevitably come in terms of violence against others and often against himself.

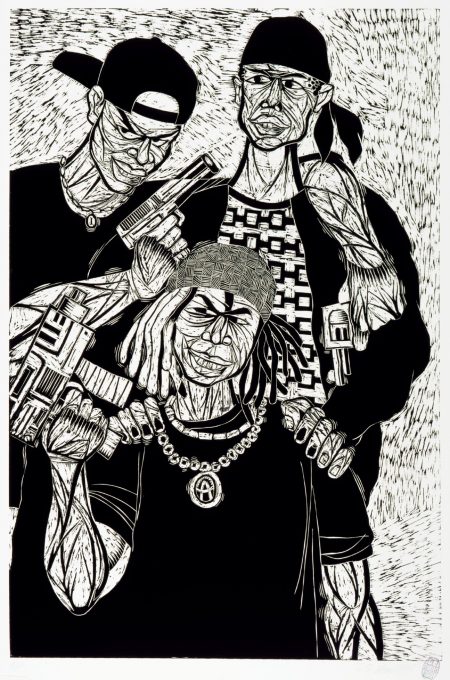

In Family, a large woodcut print from the series, Shaw represents two iconic youths happily standing behind and connecting with what appears to be the gang leader, all three of them proudly holding a gun. The title of the piece alludes to the strong ties and relationships and to all the attributes a family would provide to them, here revolving around the control and power of a gun.

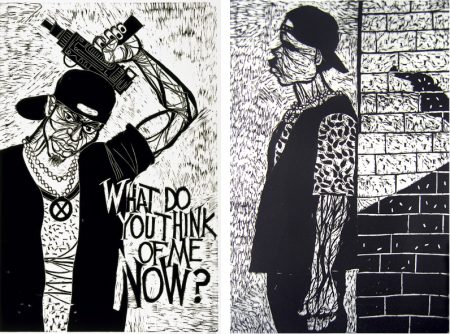

“What Do You Think of Me Now”, woodcut print, 1995, 48×32″; and The Sentinel, woodcut print, 1995, 48×32″

Shaw clarifies more explicitly his intention in What Do You Think of Me Now? which shows

the same iconic youth, wearing an X pendant, for Malcolm X, and brandishing, somewhat menacingly, a firearm above his head. In big letters is his question about his new empowering identity. Looking directly in the eyes of the viewer, he is calling attention to his new status, to the fact that he now counts and cannot be anymore ignored or belittled.

In The Sentinel, Shaw expands more on the role of the youth in this newly found family which provides him with acceptance, recognition, a satisfying sense of belonging, and an empowering and self fulfilling responsibility. The print represents a 15 year-old boy serving as a watch dog, looking out to make sure no intruder was approaching the headquarter hide-out of the gang. The boy, however, is entirely oblivious of the danger awaiting him, portrayed by a pistol behind him, that could terminate his life. His pride at being assigned the responsibility overshadows his concern for death; he would do anything for his new gang family, one that makes him feel valued and trusted.

“American War”, woodcut print, 1994, 48×32″ and The Assassination #1, woodcut print, 1992-93, 48×32″

Shaw expands more clearly on this contradictory, violence-driven situation in two related prints that address gang killing. In American War, two members from different gangs are threatening each other, both identifying themselves, through their marked clothes, with Malcolm X. Shaw’s clear statement is that this new family’s apparent stability is in reality self- destructive and war prone, not being based on the values of a natural family; and that the apparently empowering new identity will end up turning against itself. He illustrates more eloquently this point in The Assassination #1, depicting a gang member being shot down by another one.

Shaw is addressing, throughout his series, the pervasive and destructive role of systemic racism which deprives young African-Americans of an equal, equitable and stable life, one with a rich and productive identity and with a fulfilling and positively contributing pride. This racial system, instead, forces them to search for an alternative which will give them the illusion of empowerment, but sadly also exposes them to the danger of self -destruction and annihilation.

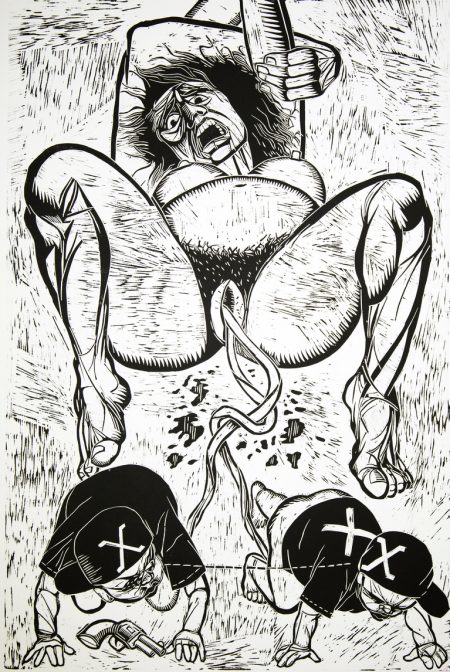

Unless systemic racism is eliminated Shaw sees this tragic situation to persevere and perpetuate itself. He visualises this thought in his print Twin Birth and a Gun in which a mother is giving birth to two sons, identified already as potential Malcolm X gang members, allured right from birth by a gun. Unless a solution is found to the prevailing injustices, more and more violence will be generated and maintained, he seems to be saying.

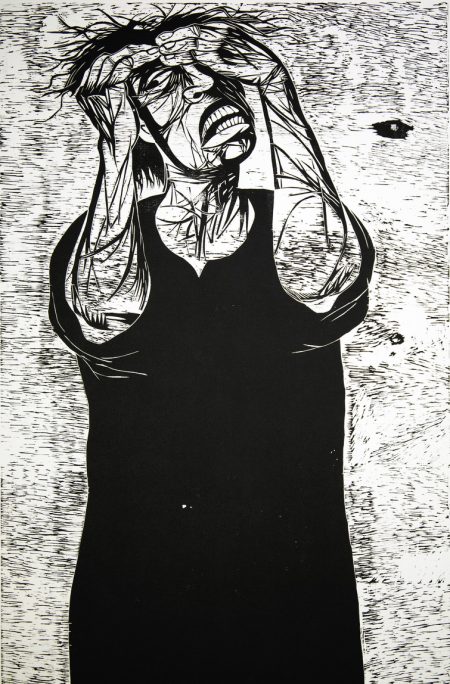

He sees also this tragic situation not only as an isolated event limited to the few, but as affecting the entire African-American community, always leading mothers to cry and lament the loss of their sons, as he represented it movingly in his print of a distraught Crying Woman.

So the answer for Shaw is clear. We need to put an end to the systemic racism that has been directed at Blacks now for four centuries. This racism, with all its associated inequities, has prevented the development of an equal African-American citizen, one who can live a stable and secure life, away from violence, benefiting from a strong and respected self esteem, and proud to contribute positively to his community and country. We need to work for a society where equality and justice impregnate all aspects of life, and this, from the beginning. We need to be given equally all conditions and opportunities for success and be respected and appreciated for who we are, rich and empowered in our diversity.

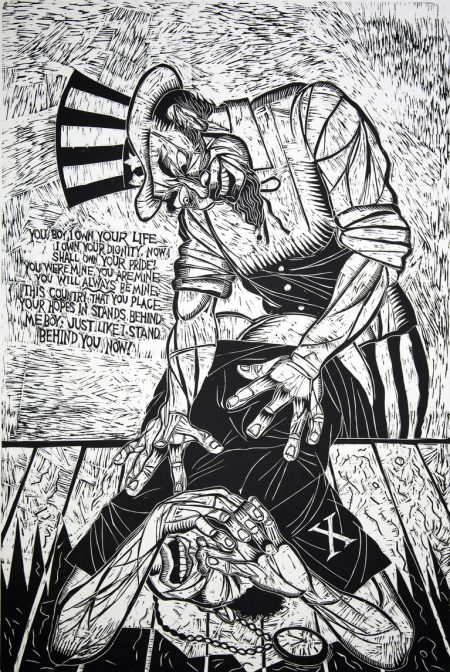

Unfortunately, at the time of the creation of his “Malcolm X Paradox,” almost thirty years ago, Shaw was not very optimistic for such a resolution. His views of the then US politics regarding African-Americans were ones of denigration, control and violence, and ones of debasing the Black youth and not recognizing all the injustices they face. His tragic and gripping print You Boy, I Own Your Life was his pessimistic and sadly realistic realization that there was no real will, then, in the USA, to address and efface racism and its deep effects on large segments of its population. On the contrary, the statement accompanying his image of ‘Uncle Sams’ violenting and penetrating from behind a Black youth reflects instead his mindset that African-Americans will never be allowed to become equal nor full American citizens and that systemic racism will be maintained as the norm to subjugate them, always limiting their rights. His painful caption on the print: “You boy, I own your life; I own your dignity. Now I shall own your pride! You were mine, you are mine, you will always be mine. This country that you place your hopes in stands behind me boy; just like I stand behind you now!” is, sadly, what the majority of African-Americans have been living in this country, now for centuries.

Shaw, who died July 6, 2010, would be pleased, however, with the current protest movements across the United States and across the world, demanding an end to systemic racism and a reversal of its accompanying inequities and violence. Americans of all ages, genders, races, etc. are coming together, speaking loud their hopes and expectations for an America as it promised to be, one of equality and justice for all. They are asking for an end to violence under all its forms, for the elimination of poverty, for the well-being of every individual, the protection of our planet, for a better world. Shaw would also be satisfied and at peace in his grave to know that, more than 30 years ago, he has started and contributed to the debate, and that his art, images and messages remain alive, raising questions, and that his earlier call to action is now being heeded by people all over the globe.

Art was life for Thom Shaw. “Artwork can be controversial,” he once said, “but we, artists, are ambassadors of truth, ambassadors of the human experience. We try to make sense of a world gone astray, and thus have an impact on people whether we intend it or not.” Shaw’s impact on people and on life in general is obvious and gaining momentum in the turbulent and tormented times we are currently experiencing.

–Saad Ghosn