The summer exhibition at Indian Hill Gallery is “Vivid Prints: Kevin Harris and Saad Ghosn.” Powerful feelings or strong, clear images in the mind are vivid. Strong colors that are very high in chroma are vivid. Casey Dressell, curator and exhibition coordinator, organized the show and named it, making vivid the first thing to think about.

When I walk into an exhibition, I like to stroll around the gallery to get a sense of the work. Here the first two prints, one by each artist, suggested a quite different show. The images addressed similar themes, and I expected the rest of the show to follow that strategy. I was wrong.

Saad Ghosn, les visiteurs du dimanche (sunday’s visitors), 2020, woodcut, 22” x 30”

In Indian Hills Gallery’s handout for the exhibition, Dressell concisely described Ghosn’s woodcuts as “utiliz(ing) direct, stark, and simplified imagery to convey his (sociopolitical) message.” They are definitely vivid.

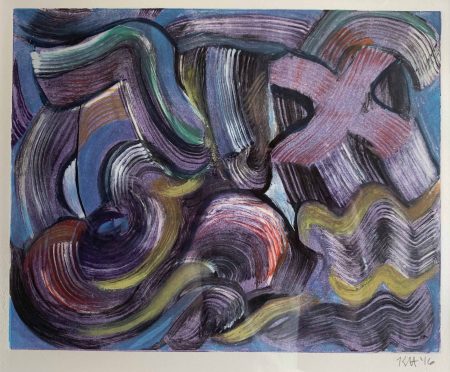

Kevin Harris, Ron’s Crew et al BCN II, 2019, solarplate intaglio on monotype, 10” x 8”

As for Harris, Dressell writes that the artist “employs a wide range of media and uses both traditional methods and contemporary technology ….” The artist also “explores a variety of themes in his work.” Those two sentences could describe the work of any number of artists, and I am clueless as to what Harris’s artwork looks like.

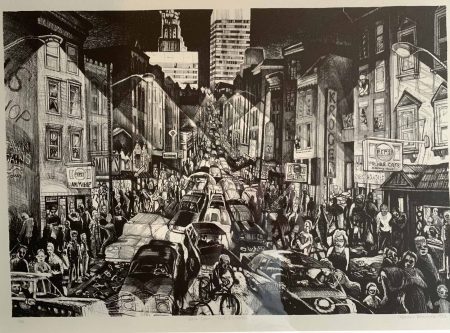

Saad Ghosn, a malin malin et demi, 2020, woodcut, 22” x 30”

Unlike Harris who is absolutely promiscuous in his choice of techniques1 (nine for his18 prints on view), Ghosn has been faithful to woodcut, exploiting the boldness of the technique and the noncolors of black and white.

Ghosn was born in Lebanon in 1951. He received his medical training in Beirut, Paris, and the U.S, but is self-taught as an artist. In 1976 he moved to Boston and became aware of the fine art world.

His next stop was Cincinnati in 1985. While practicing medicine and being Professor of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati (now retired from both), he was prolific as an artmaker addressing social and political injustices. Daniel Brown, editor of aeqai.com, observed that “artmaking for Ghosn is a means of expressing his isolation as well as injustices he sees wherever he goes.” 2 Believing the visual arts can be a vehicle for peace and justice, in 2003, he founded SOS (Save Our Souls) ART Cincinnati, an annual weekend festival of non-juried exhibitions and presentations by writers, poets, performing artists, and others.

Saad Ghosn, the observer 6, 2010, woodcut, 6 ½” x 8 ½”

Ghosn’s black-and-white woodcuts were made in 2010 or in 2020, but you would be hard pressed to determine which year as his style has remained consistent.

In Ghosn’s the wait, three people–a man, a woman, and an androgynous figure–all dressed in suits made of a squiggly-patterned fabric–sit on straight-backed chairs.

Saad Ghosn, the wait, 2010, woodcut, 22” x 30”

A circle on the wall could be a clock, but there is no clockface, only concentric circles with a black center, a void indicating the scene is timeless. The trio is not interacting, conveying a sense of isolation and alienation. Where are they waiting? What are they waiting for? How long have they been waiting? How much longer will they wait?

Kevin Harris, Rooms on Race, 1988, lithograph, 11” x 15”

Exploring a similar theme is Harris’s 1988 Rooms on Race. In the lobby of a sleazebag hotel, rates starting at $10 a night, a group of zombie-like men sit in the lobby, each in a zone of their own. What are they waiting for? Somehow I don’t think it’s because their rooms are being cleaned.

Kevin Harris, Garfield’s Lounge, 1988, lithograph, 11” x 15

Harris’s 1988 lithographs Garfield’s Lounge

and

Kevin Harris, Walk Down Vine, 1988, lithograph, 18” x 26”

Walk Down Vine are also figurative; they share the same aesthetic and message of isolation and alienation as Rooms on Race. I find these prints Harris’s most successful, which saddens me because they are the oldest works in the exhibition. His experimentation with other mediums and subjects produced less felicitous results to my eye. 721

Kevin Harris, New Mexican Hoo Doo Breezes 1, 2016, monotype, 8” x 10”

When I finished my circuit of the gallery, I tried to understand why Dressel had paired these two artists. They didn’t share a technique, subject matter, or aesthetic. And while Ghosn’s works were vivid, I found nothing vivid in any of Harris’s efforts.

Kevin Harris, ZXXXDXSHOCKNLGOTIC II, 2019, 10” x 8”, solarplate intaglio on monotype

Harris is all over the place: figurative, abstract, black-and-white, color, subject matter, handling. He used nine different printmaking techniques. The only thread tying it all together is that it was all done by Harris. I can discern five different styles and, therefore, the possibility that the prints were done by five artists. Instead of a two-man show, a case could be made that “Vivid Prints” is a group exhibition.

Dressel intended the exhibition to provide “a glimpse into the observations and artistic practices of these two educators and world travelers.” They are educators; I can’t quibble with that, Ghosn through his sociopolitical activism, and Harris who has taught all over the country and, since 2000, at Sinclair Community College.

Are they “world travelers?” Ghosn was born in Beirut and has lived in Paris, Boston, and Cincinnati.

Kevin Harris, Osaka, 2019, laser-cut woodblock, 4” x 6”

My best guess about Harris’s travels is that he spent time in Japan in 2019 because of his prints of Osaka and Asakusa,a Japanese temple; I don’t know what other stamps might be on his passport.

Kevin Harris, Asakusa, 2019, woodcut chine-collé 3 on monotype, 8” x 10”

I don’t know why Dressel paired these two artists. They have only one thing in common: they are printmakers. Ghosn sticks to woodcut and bold images. It’s a coherent body of work.

Harris is at loose ends, unable or disinclined to commit to one technique or to one style.

Kevin Harris, Ron’s Crew et al BCN II, 2019, solarplate intaglio on monotype, 10” x 8”

I was wrong to think that the prints would be arranged thematically. I was frustrated in trying to find something “vivid” in both artists’ work. What I did find “vivid” was the difference between the two artists’ work. That alone warrants the short drive to Indian Hill.

Saad Ghosn, histoire triangulaire (triangulaire story), 2020, woodcut, 30” x 22”

–Karen S. Chambers

“Vivid Prints: Kevin Harris and Saad Ghosn,” Indian Hill Gallery, 9475 Loveland Madeira Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242, 513-984-6024, info@indianhillgallery.com, through August 8, 2021

Endnotes:

1 The gallery provided a glossary of terms to explain Harris’s technical arsenal that includes lithography, intaglio, monotype, woodcut, laser-cut woodcut, woodcut chine-collé on monotype Moku Hanga (traditional Japanese method of woodblock printing using water-based inks and transparency. Ink is applied with brushes for greater variation in ink density), solarplate (intaglio process using a light sensitive plate instead of a traditional acid bath/ground. A drawing on transparent substrate [mylar, plexiglass etc.] is placed over the treated plate and exposed to light [similar to a photographic printing process.] The exposed plate is washed in water, the unexposed areas wash away leaving incisions to hold the ink.) solarplate intaglio on monotype.

2 Daniel Brown, “Woodcut Prints With a Sociopolitical Purpose,” artistnetwork.com/artist-profiles/woodcut-prints-with-a-sociopolitical purpose/

3 The technique of chine colle involves a tissue thin paper, usually of a contrasting color and cut to the size of the printing block or plate, which is embedded into a thicker support paper during the printing process.