After working with traditional mediums for nearly twenty-eight years, Los Angeles based artist Echo Lew grew curious about the effects of light in motion and began experimenting with photography. Not only did this investigation lead him “to spontaneously tap into decades of drawing experience while the camera’s shutter was open,” as conveyed by Lew himself, but it provided him with a means to express his experiences as both an inventor and a fine artist.

The son of two Taiwanese farmers, Lew grew up alongside seven siblings, all who spent their youth farming their parents’ small acreage of land. Responsible for leading the family cow to grass throughout his youth, Lew occupied most of his days drawing in the sand or building sculptural formations out of natural materials.

Lew always knew that he wanted to be an artist, but it wasn’t until the Republic of China was reduced from the mainland to Taiwan (after the civil war) that he was given the opportunity to obtain an education, an incentive offered by the government in an attempt to boost industrialization.

Lew wanted to study fine art but when provided the chance to attend college he followed his parents’ advice to pursue something more practical, and he majored in navigation for the merchant marine. According to Robert Seitz, however, Lew did in fact skip most all his “classes to audit art courses, where he spent more time in the studio than students who were taking that degree.” Yet, never once did Lew regret his decision to do so. Rather, he felt such provided an added benefit to his education, which he understood and still sees as an ever-growing process rooted in experience.

Upon graduation, Lew found that life at sea gave him opportunities that he would never have had if he had opted against his parents’ advice. Not only did the job give him the chance to visit eleven new countries, but it also allowed him to further his studies in art, which he did by exploring museums worldwide while on shore leave.

The only one in his family to ever leave Taiwan, Lew eventually emigrated to the United States. In doing so, he undertook an ambitious path. The confidence he’d gained at sea provided him with the drive to begin a design business from which he ultimately profited with the production of more than 50 patents for various bodies of ballpoint pens that he invented specifically for those working in the field of medicine. Lew attributes his success as a designer to his studies in art, but it’s hard to ignore the role that his parents’ urging for practicality played in the evolution of his innovative endeavors.

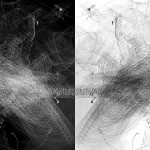

Lew’s initial exploration with light as an artistic medium first came to fruition in a series that comprised his 2006 Los Angeles solo exhibition, See the Light. Mounted at the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, this seminal show didn’t just reflect how formative Cy Twombly and Jackson Pollock had been in Lew’s ongoing investigation with spontaneity and line, but it marked a starting point from which Lew began to delve into and explore the possible effects of light in motion.

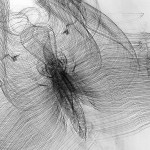

To truly appreciate Lew’s newest works that comprise his solo exhibition, Drawing in Space, currently on view at the Orange Country Center for Contemporary Art, one must understand the history behind his technique, which, like Lew’s life experiences, is as equally based in aesthetics as it is in utility.

The first motion studies date back to the late 1800’s and were engineered by Étienne-Jules Marey and Georges Demeny. The pair was the first to capture details of motion never before attained through their investigation of the phenomenon of movement, which they did by making multiple exposures of an individual in motion on a single photographic plate.

While Marey and Demeny’s efforts opened the door for many to follow, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth are respectfully credited for their work in motion study during the early 20th century because of the contributions they had upon the utilization of manpower.

In 1914, the Gilbreth’s conducted a series of experiments for the purpose of tracking the motions of clerical and blue-collar workers by use of small lights and time-lapse photography. The results proved invaluable, providing the two with information that they couldn’t have acquired otherwise. By isolating distinct variances between random bricklayers, for instance, they were able to enhance the productivity within the brick and mortar industry by shortening the brick laying process of one brick from 18 to 4 ½ movements.

Around the same time, the Italian Futurists were also utilizing similar experiments but instead for aesthetic purposes. As offered by Peter Frank, “the Futurists were interested not in efficiency so much as in the allure of dynamic motion itself, with its provocative implications of radical social change and its projection of artistic invention into a fully mechanized world. Like the Gilbreths, Futurist photographers were leaving their shutters open to catch motion; but for them, it was the motion itself that fascinated.”

The history that follows was explored by both engineering practitioners as well as fine artists. Man Ray, for example, began playing with light and suspending the opening of the camera shutter. The results of these experiments are what led to his Space Writing series dating back to the mid 1930s. Then, in 1949, Picasso threw his hand into the mix after the Albanian born, self-taught photographer, Gjon Mili, had been assigned by LIFE to photograph the artist for a feature spread.

Prior to working for LIFE, Mili had spent the previous decade working with Harold Eugene Edgerton at MIT in an attempt to pioneer photoflash photography. Like their predecessors, they aimed to study human movement. Upon their discovery of photoflash photography, the two soon found that they could capture the line of movement of any one thing in motion. Yet, it wasn’t until Mili “attached small lights to the boots of ice skaters then opened the shutter of his camera,” that he created what would become “the inspiration for some of the most famous light painting images ever created,” as offered by Jason D. Page.

When Mili traveled to the South of France to photograph Picasso, he showed him his images that he had produced, photographing figure skaters. Immediately inspired, Picasso reached for a penlight and spontaneously began drawing images in the air. These Mili captured on film and are what we now know as Picasso’s Light Drawings, the most famous of which remains “Picasso Draws a Centaur.”

Since, this photographic technique has continued to evolve and thus been utilized as a tool for artistic exploration. For Lew, his process requires several hours of preparation, after which he uses just a single shot to obtain a single image. And it is during the exposure time of approximately one minute that he manipulates an array of selected lights in front of the camera to create each of his own “light drawings.”

As an abstract painter who, for many years, had been concerned with line, shape, composition, and concept, Lew’s foray into digital photography has enabled him to evolve creatively with limitless potential. While he continues to draw upon others for inspiration, his newest accomplishments are nothing short of phenomenal. Not only has Lew produced a beautiful body of work that embodies a cohesive fluidity, but each piece included in Drawing in Space simultaneously emits an intensity comparable to that of a ocean’s crashing wave while at the same time a graceless ease emblematic of a Baroque symphonic composition. Bottom of Form

Echo Lew’s solo exhibition, Drawing in Space, will remain on view at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art in Southern California through May 30. Lew’s artworks have been featured in numerous galleries and remain in various private collections throughout the United States, Japan, Italy, Taiwan, and China.

–Anise Stevens