Perhaps the first stanza of the 113th chorus in Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues (1959)—his both critically praised and abhorred epic poem of scat-sung, jazz-imbued stanzas—might serve well as a preface to Bernard Plossu’s photographs of Mexico:

Yet everything is perfect,

Because it is empty,

Because it is perfect

with emptiness,

Because it’s not even happening.

Yet the lines reflect a different sentiment than Plossu’s, whose monochrome photos in ¡Andele! Mexico in Bernard Plossu have the mesmerizing ability to document what is happening, though it might not always seem so at first glance. But like Kerouac’s poetry, Plossu is able to reveal the sublime in everyday experiences. He describes his style as being “like it is,” and although it might be a trifle oversimplified, it suits his approach well. Shots of lonely men behind shop windows, stray dogs on the beach and women wringing wet laundry vividly invite us to marvel at the starker beauty of life’s realities.

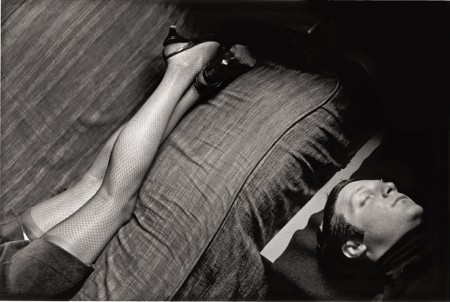

The exhibit offers up a unique perspective of Mexico during three pilgrimages Plossu made in 1965, 1974 and 1981. The oldest photographs let us see the country through the eyes of a 20-year-old Frenchman newly arrived and armed with a 50mm lens. The twenty-eight photographs form a photographic travelogue, a road trip through Plossu’s Mexico, which is in many ways the same Mexico of Beat Generation lore. But his view of the country also includes semblances of nouvelle vague sensibility—the artist credits the movement for teaching him about shooting with the “camera at shoulder.” Plossu mélanges Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photojournalist eye, the technique that Truffaut termed the “camera-stylo,” and the poetic imagery of the Beats to create a distinct and aesthetically curious style. Influenced by American films like Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954), Plossu’s 50mm lens and his attention to details that distill the mysterious in the mundane lend the photographs a cinematic quality. For certain, there is a mise-en-scène about his visions of Mexico—portraits of young girls in alleyways, tired limbs hanging out of the backs of cars and the bedroom noir of two sleeping strangers seem like stills from a film adaption of Kerouac’s Tristessa (1960). But there are also a handful of more abstract photos that capitalize on the editing—or lack of an editing—process, and are lent a wondrous “accidental” quality. In one of these, a long, double exposure shows a shadowy figure looking up, above him the faint traces of a ghostly angel. It is the juxtapositions in Plossu’s retrospective that reveal his aptitude at taking both carefully composed photographs and serendipitous snapshots—for him, the two modes are compatible. Like many Americans shooting the early sixties, Plossu’s photos rely on disjunctures and off-centered framing to endow meaning and emotion. His style mirrors Robert Frank’s in The Americans, his masterful album of handheld snapshots, and it’s interesting to think of this exhibit as a less politicized Mexican companion piece to that seminal and controversial work, whose 1959 edition, not coincidentally, contained a small forward penned by Kerouac himself. “With one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world,” he wrote. The same could be said of Plossu, but for Mexico.

Richly evoked textures abound in the exhibit, from pockmarked shoals to fishnet stockings. This is owed in part to the high-contrast Kodak Tri-X film, a grainy stock popular among photojournalists before the advent of digital photography, and Plossu’s chosen medium throughout the last five decades. Many images are softened by a blurriness that seems both deliberate and unintentional, forsaking the sober geometries of some of his later images for an otherworldly quality. Indeed, reading his photographs chronologically reveals a stride away from the portraiture that defined his early images and toward capturing the empty landscapes that exist in parking lots or tropical resort areas. Yet in an intriguing move by curator William Messer, the photographs are arranged nonlinearly, allowing the three periods of image-making to exist almost timelessly; if the photographs were not labeled with letters to indicate the year they were taken, it would be difficult to place the time. The storefronts, cars and hitchhikers could exist in any of the eras.

In continuing with Messer’s proclivity to exhibit established artists, Plossu is a highly-recognized photographer, though much more so in Europe than America, the latter of which has only shown these works twice, this exhibit being the second time. Aperture has published a book of Plossu’s Mexico photographs titled ¡Vámanos! Bernard Plossu in México, a title Messer curiously transposed, implying that Mexico is inextricable from these photographs just as much as Plossu is.

In what is one of the exhibit’s quietly spellbinding images, a group of men crowd around a mobile home by the side of a road in what is both a portrait and landscape. Leavened with stratus, the sky is impossibly large, and against the horizon of disappearing telegraph wires are the profiles of the men on the road. Looking at the image tells you a lot about Plossu’s photography, as the why is frequently not as readily understandable as the what. With the camera positioned far away enough to remove the photographer fully from the subject, it is evident that you’re witnessing something, but that something could be anything. Plossu’s Mexico arrests moments that range from stunningly pristine to as nebulous as a forgotten memory, and this reflects in part the malleability of culture itself in the mid-sixties and seventies. Yet if you step back far enough, you can see it, in both its pristine boldness and its dreamlike haze—a world, perfectly empty, in flux.

¡Andele! Mexico in Bernard Plossu runs through June 7 at Iris Book Café.

–Zack Hatfield