Jimi Jones, ever the graphic designer, is in the billboard business as evidenced by his current show at the Springfield Museum of Art. Jones views his role as an artist who explores and celebrates the African American cultural production as well as being a storyteller in an historical context. His large oil and acrylic canvases combining graphic design, painting and collage, juxtapose historic and contemporary pop culture icons to explore social-political issues from the African American point of view.

His illustrative manner is marked by stylized pixilation, bright primary color schemes and graphic geometrical elements.

During his artist talk, Jones recounted his earliest childhood experiences, watching as his father made his expressive art. One of the larger pieces in the exhibit is a 6′ x 12′ canvas titled “Why these cultures?” In collocating cultural symbols and iconic elements of the African and Asian cultures on opposite sides of the canvas, Jones initiates a conversation on dualism that asks the viewer to bring his/her interpretation and experience to the telling of the tale.

In the 6’x12′ canvas entitled “Martyrs”, the dominating central cluster of figures is lifted from a classic Raphael composition. A monochromatic lifeless Christ is being carried by grieving disciples toward interment. The chromatic jewel-tones of their attire jarringly contrasts with the brown/white imagery of the rest of the painting. Surrounding the disciples and their Christ are fractured photos of the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, his disciples pointing toward the source of the fatal gunfire. A somber Lincoln observes all from his memorial and in the bottom left, a thoughtful, inquisitive JFK queries the viewer and awaits a decisive reaction.

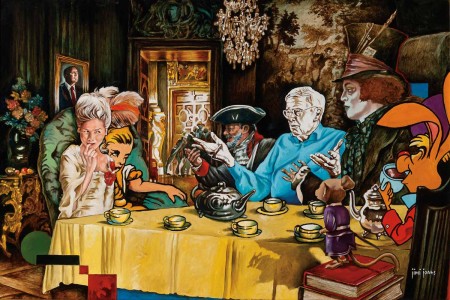

Another painting spoofs a wrinkle in the current political scene and is titled “The Tea Party”. High Tea is set in a palatial setting, but the numerous guests are interspersed with a menagerie of Alice in Wonderland characters. Cross conversations and nagging details allude to the backstory. From the formal chair on the left, a drug-eyed Alice flirts dreamily with a Johnny Depp “Mad Hatter”. The flop eared Crazy Hare in the high-backed chair on the right reminds us to mind the pocket watch. At his side, the properly frocked mouse observing the occasion seems friendly enough, but on a closer look, his shadow morphs into a sinister, vicious squirrel on the vertical drape of the bright yellow tablecloth. But while the whimsical characters occupy the head of table positions, Jones draws attention to another conversation in particular by portraying the two characters in monochromatic tones in this otherwise full color painting. Seated at ‘tea’ is one of the billionaire Koch brothers while the painted portrait of the other brother glowers over the scene from the dark recesses above the pursued conversationalist. She is Marie Antoinette, whose presence as the harbinger of social revolution, chills the fantasy and flavor of the piece. The historically aware viewer, reflecting on the original grass roots connotation of “Tea Party” may contemplate the large corporate backers currently at the table, pawning the concerns of the common person in favor of their multifaceted agendas.

In a painting depicting John Wayne and Lil’ Wayne, cowboys riding hard in the wild west are the pictorial background for the full color onslaught of John Wayne on his mount. This image is paired with a full figure of Lil’ Wayne, a contemporary rapper. The painting’s title poses the question “Who’s the real Cowboy?” Jones hopes that the alignment of these diverse cultural icons from different but recent decades will prompt a discussion on how the grand depiction of a pop culture icon shapes a national identity. More specifically, he points to the rise of contemporary African-American identity through the rapp-gangsta culture. This theme mushrooms in the giant red painting entitled “Hoods in Hoods”. The triple entendre title may refer to the common black community gear wear, the jargon term synonymous for ‘thug’ and the shortened slang designation for neighborhood, specifically the black ghetto ‘hood’. The depicted black pop culture personalities “are all multi-millionaires”, said Jones in his gallery talk. What is Jones’ intention in painting this painting? to debunk the myths? to idolize the culture? You decide.

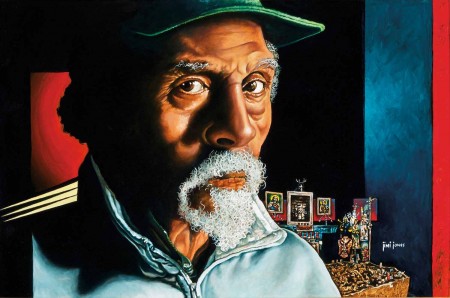

On a much smaller scale, Jones presents two series of oil portraits: likenesses of supportive friends and mentors in his personal circle and a series of black jazz and rock musicians. These paintings trade heavily on dominating likenesses that are technically well rendered with aspects of story telling details or design elements to complete the canvas space. In the first group, the selected subjects act like an autobiographical visual charting Jones’ development as an artist. In Jones’ portrayal of Thom Phelps, a fellow member of the Neo-Ancestralist group, the subject’s stark stare is confrontational and unwelcoming. Over his shoulder one can see elements of Phelps’ symbolic art which seeks to realize ancestral connectivity, the stated mission of the group. Another canvas depicts the open visage of Gordon Salchow, professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati DAAP, who mentored Jimi Jones the student in his design studies. Also portrayed are Carl Solway and Owen Findsen and several other mutual friends and artists in the regional community.

Lastly, the musician series pays homage to the hallmark contributions of jazz and blues greats Miles Davis, Monk, Coltrane and Billie Holiday. Jones credits the iconic Jimi Hendricks as his motivation to change his name from James to Jimi.

The first floor gallery is enlivened not only with the bold color and geometric pixilating patterns of the large works but also by the juxtapositioning of ideas. The visitor to this exhibit is challenged to put on his mental boxing gloves with almost every encounter.

Marlene Steele teaches and paints in Cincinnati Ohio.