I just returned from Lebanon, where I helped organize in Beirut the 1st SOS Art Liban event.

SOS Art, which stands for “Save Our Souls” Art, is a collective art exhibit and a festival of the arts focused on creative expressions for peace and justice. It was started in Cincinnati in 2003 at the beginning of the invasion of Iraq, prompted in fact by the earlier Cincinnati racial riots of April 2001, the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001 and the launch of the war against terrorism by the Bush Administration. Due to the then prevailing atmosphere of fear and intimidation caused mostly by the implementation of the Patriot Act, artists felt unable or unwilling to express themselves freely and communicate through their art their sociopolitical views of the time; they also felt isolated and silenced in their beliefs.

SOS Art was intended initially to provide them with a friendly venue to voice their concerns, to break their isolation by connecting with other similar artists and to create a dialogue with viewers and visitors regarding important timely matters. SOS Art, however, having become annual, quickly expanded to include additional broader aims, namely those of i) encouraging, promoting and providing opportunities in all the arts as dynamic vehicles for peace and justice; ii) encouraging artists to use their art as their voice on issues that concern them, their community and the world; iii) forging a community of local artists who will network and collaborate together, using art as a means to impact issues of peace and justice where they live; iv) using the arts to speak about, inform, educate and create a dialogue on issues of peace and justice, thus bringing about positive change.

SOS Art, now in its 14th year in Cincinnati, has had from the start, and has kept all along, a local focus and dimension, meant essentially for local artists and for their role and involvement in their local community. Being originally from Lebanon and having more time at hand due to my recent retirement, I had a definite interest in duplicating the local characteristics of SOS Art in Lebanon, and therefore decided to transplant it there with the hope of achieving the same goals.

SOS Art Liban took place for a week, in February 2016, at the Unesco Palace in Beirut. It consisted of a collective art exhibit and of a festival of the arts (poetry reading, movies, play, storytelling, dance, debate…), all under the overarching banner of peace and justice. 108 individual visual artists as well as 5 students, 12 and 13 years old, representing a middle school, participated in the art show. They came from many parts and cities of Lebanon (Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon, Tyre, Zahle, Nabatiyeh…) and used different art mediums (painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, photography, video) in their work, each providing their own message. It was noteworthy, however, that some well established artists refused, or were made to refuse by the gallery that represented them, to take part in the show, objecting to having their work displayed next to less well known artists or even unknown students for that matter. This was contradictory to the democratic, egalitarian basis of SOS Art Liban, the main purpose of which is to promote the voice and the message of the artists rather than their elitist and egotistical notoriety. SOS Art Liban was in this respect different from other collective art shows organized in Lebanon, and hopefully one that will trigger a new spirit and a novel approach in the future.

The visual artists included in the show were selected based primarily on the appropriateness of their works to the themes of peace and justice and to the inclusive character of their message; their artistic merit was also taken into consideration.

As compared to the artworks submitted at SOS Art shows in Cincinnati, the Lebanese artists were more careful and more prudent in their handling of the themes of peace and justice. A good number took a general and conceptual approach to them, addressing, for example, what they meant, the symbols used to represent them, the feelings they create, instead of tackling daily social and political issues relating to them and that could be perceived as inflammatory. This was to a certain extent expected especially in view of the heightened sensitivities in a country that has experienced violence and wars and that is still politically unstable with neither a current president nor a strong government.

In “Yasmina,” for instance, a mixed media painting on canvas, Ahlam Abbas represents a woman standing on a flying carpet, looking from above, down upon a city, feeling free. To the right, also flying, is a white dove, symbol of peace.

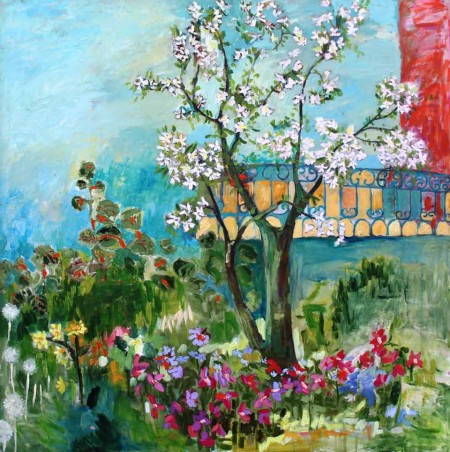

“Peaceful Flowers,” a large oil painting by Layla Al Moussawi, depicts a beautiful flowering almond tree, erect in a peaceful setting of a lush green and colorful nature. “My painting tries to express peace through flowers,” says Al Moussawi, adding: “because peace grows like flowers and flows like water.”

Gilles Abou Debs conveys his message of peace and justice using abstract colors. His mixed media “Ascensions I & II,” vertical in their composition, progress from an agitated dark atmosphere at the bottom to a serene light one at the top. For him, to be just and to want peace is an individual rather than a collective trajectory. His vertical pieces mean to express the passage from the earthly, the material, to the immateriel, the spiritual, a “possible but difficult path from the confused to the more just,” as he states.

Some artists used the general theme of childhood when referring to peace; they stressed the need to protect childhood by all means for the survival of society.

Dina Abdel Kader, through her painting “Childhood,” calls to the rights of children for safe and decent living conditions and to our obligation to provide them with all physical and emotional needs in the forging of a peaceful future. And Yolande Naufal, in her large oil painting “Garden of Peace,” shows children playing together in harmony, respectful of each other, coexisting in tolerance, peace and solidarity, thanks precisely to the positive environment given to them.

In a country where religions have always been used to divide and stir violence, many artists focused their message on the desired peaceful coexistence between religious communities in a diverse Lebanon.

In her mosaic “Beirut, Cosmopolitan City,” Pauline Avedissian Sakr represents a typical and harmonious Lebanese urban landscape where churches and mosques are within reach of each other. “Where there is peace, there is a mixed communal life where all religions are respected and tolerated,” she says.

German artist Dagmar Hodgkinson, who has lived in Lebanon now for over 50 years, refers in her watercolor “Deir El Kamar” to the predominantly Christian village which has served as a symbol of peaceful coexistence with Moslems throughout history. By including a mosque in her image, Hodgkinson means to cast shadows on the sad civil war years that, still not too long ago, tore the country apart.

In his acrylic painting, “Peace in the Old Beirut,” high school student Anthony Abdel Karim, on the other hand, represents peace as it used to be in Lebanon and as he would like to see it again. He paints a peaceful and idyllic quarter of the capital, Bab Idriss, as it was many years ago before the war. It shows happy people coexisting and interacting peacefully despite their differing religions.

Other artists addressed the interplay between peace and justice and the fact that one cannot exist without the other.

Liane Mathes Rabbath, an artist from Luxembourg now living in Lebanon, created a 2 part metal sculpture titled “The Dress of Hope.” Each part of the sculpture represents one half of the dress, one, riddled with bullet holes, alluding to war, and indirectly to peace, and the other, hammered with a judge’s gavel, to justice. Rabbath’s message is simple: in order to form a complete dress, one that will be able to dance, both parts need to unite.

Many other artists, on the other hand, confronted in their work daring contemporary and local sociopolitical issues affecting peace and justice. These included, among other subjects, violence and war, local politics, women’s rights, the problem of refugees, the abuse of the environment, the materialism of modern life…

Farouk Grissom, a twelfth-grade student, used plastic toy soldiers in his mixed media installation “Toy Soldiers.” He assembled them in a way so that their projected shadow revealed the image of a large rapacious crow preying on a smaller one. It was his commentary on wars and on the hidden motives behind them, always benefiting the powerful at the expense of the poor and vulnerable.

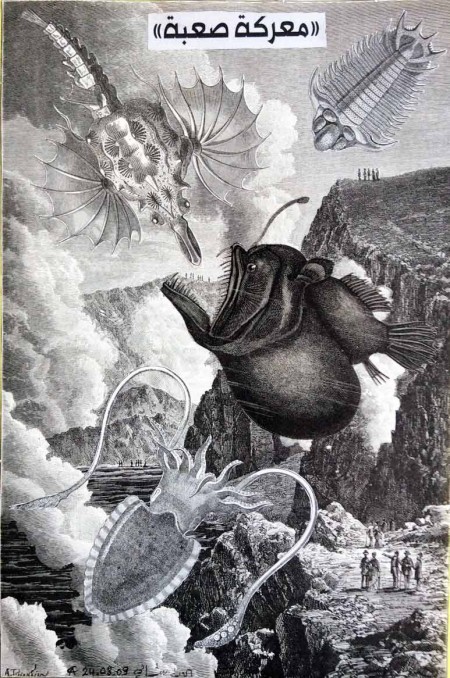

In his collage “A Difficult Battle,” Lebanese artist Alain Chemali, resident of France, points to the current devastating struggle in the Middle East between Saudi Arabia and Iran, using the Sunni and Chiite populations as proxy. Sadly, one can easily conclude that there will be no winners, just losers, in view.

Mycal El Khoury, also a Lebanese artist residing in France, addresses in her acrylic painting “The Screams of the Lacking Bodies,” the atrocious beheadings committed by ISIS.

Merheb, George, A Mediterranean Odyssey, mixed media on cardboard and burlap; 40″x400″ (shown detail)

An American Beirut-based artist who teaches art at the Lebanese American University, Lee Frederix created a mixed media, free standing and double sided sculptural panel he titled “Big Bad Wolf.” It states his criticism of the recurring use of car bombs in political assassinations in Beirut, as well as his condemnation of the physical violence carried out with impunity and outside the realm of law in the streets of the capital.

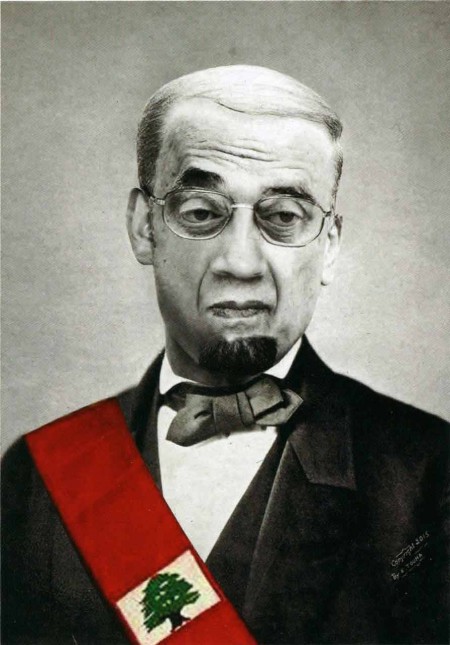

Eliane Touma, deploring the continuous absence of a President to the country after almost 2 years of failed bickering negotiations between the various political parties, decided to create one on her own. Her photomontage “Anachronistic Assemblages (Our Fictitious President)” consists of collaged parts of the faces of various current political leaders. Unfortunately the result just proved anachronistic and a failure.

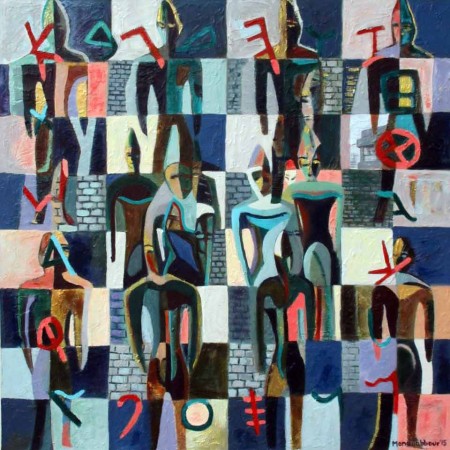

In her mixed media acrylic painting “Phoenician Pawns,” Mona Jabbour, also an art teacher at the Lebanese American University, reflects on the Phoenician origin of the Lebanese people and on their current status in their own conflicted land and in a world devoid of peace and justice: “My Phoenician pawns refer to us Lebanese,” she says. “They are defiant, manipulated through a brutal political game…”

George Merheb, on the other hand, in his 33 feet long mixed media “Mediterranean Odyssey,” speaks of the Mediterranean civilizations which have been the sources, from antiquity up to today, of all cultures and conflicts at the same time. “A conflicting paradox that is lived daily by the people of the area,” he notes.

The problem of refugees in general, and of Syrian refugees in particular, now in very large numbers in Lebanon, was the subject of many works.

Tabesh, Thuraya Zakaria, Message for Peace and Justice, mixed media, acrylic & oil painting on canvas; 27″x27″

Bidawi, Ranim, Those Who Lost Their Right to Speak, silk screen, acrylic, paper on cardboard; 28″x40″

Lina Boghossian, a Syrian artist who left her country because of the war and is now living in Lebanon, represents in her silk screened acrylic painting “The Displaced” silhouettes of fleeing people aiming for better horizons, for a stable and peaceful life.

Arlette Sauveur Abidaoud uses the same theme in her papier mache and drift- wood sculpture “The Raft.” It shows people sitting tightly on a raft, facing a dangerous sea, hoping to make it safe to a kinder and more serene place.

And Thuraya Zakaria Tabesh portrays in her mixed media painting “Message for Peace and Justice” the desperate fate of many of these helpless refugees, similar to that of this little boy drowned and thrown by the shore.

In her mixed media silk screen “Those Who Lost Their Right to Speak,” Ranim Bidawi makes, however, a larger statement, depicting a Syrian refugee child with a gun placed on top of her mouth. War and conflicts not only made the child a refugee, but also silenced her and took away her childhood.

Women’s rights and women’s conditions in the Arab world were also tackled by many artists.

In “Darkness,” a mixed media painting, Nadine Zahreddine represents a lonely, naked, isolated and somewhat desperate woman, sitting curled up in the dark, surrounded by a shattered world of broken glass. “The woman is searching for her rights; she has been struggling to survive, always shut out while asking for freedom,” says Zahreddin.

And Rasha Ibrik confronts with courage the situation of the Muslim Arab woman, “in a world where external forces dare to pin her down and restrain her from basic rights to life,” she states. Her photograph “Hidden,” is part of a series “Woman” based on modern women’s conflicted plight against oppression in the Middle East.

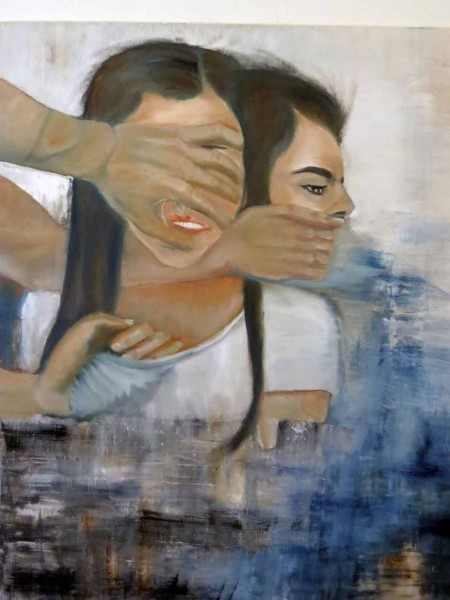

Myrna Abdul Sater’s poignant oil painting “What You Allow Is What Will Continue” addresses domestic violence and violence against women. The woman she portrays is silenced, blinded and physically abused.

Concerns for the environment were expressed in other works.

Using a mannequin that she dresses with a wedding gown made out of plastic water bottles and that she titles “Beirut,” Souraya Hallal makes a strong statement about the imperative necessity to pay attention to our natural resources and to the sorting and recycling of our waste.

A large number of works addressed also various and disparate issues pertaining to our general world, our society, our values…

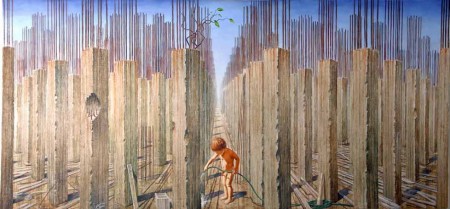

Antoine Mansour, for instance, reminisces on the lost child in each of us and on the excessive materialism that has corrupted our values and our innerselves. His sand and oil painting “Raphael Watering Concrete Pillars” shows a child watering a world of concrete pillars and growing, despite all odds, a green plant. “My painting is a call to retrieve the other one within us, the human being who struggles daily in a material modern life, and who, unfortunately, is endangered by egoistic purposes, by the greed of money and the search for power,” Mansour says. He adds: “This human being, however, can be secured when retrieving the noble values of human relations and the endless source of universal Peace and Love.”

In his oil canvas “That Which We Contemplate We Are,“ US-based Lebanese artist Chawky Frenn reflects on the brokenness of a system that puts personal and party gains and power over the common good, thus bringing injustice and suffering to an enslaved population.

Hannah Millet, a young college student, uses her oil on gel painting “A Warning,” to warns us about the future. Centered around a frightening gas mask, her painting means to remind us of the disastrous effects of pollution, war and oppression, and of the pain they elicit.

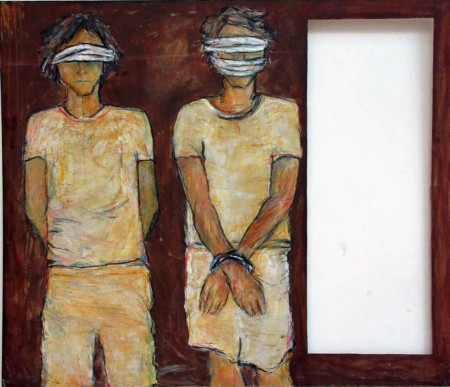

And Mouna Bassili Sehnaoui notices that sadly things have not much improved in the beginning of this 21st century. Her 7 acrylic on canvas panels “State of the 21st Century” each addresses one of the major problems she sees still exists in the world. We’re putting up “Walls” instead of spreading love and compassion. Bombs kill civilians whom we dehumanize by labeling them as “Collateral Damage.” When justice is not equal for all it may lead to “World Trade” disasters. “Human” and “Animal Mass Graves” are still revolting realities. Innocent individuals are often victims, and for unjustifiable reasons, of “Hostage” taking. And so many “Missing” people disappear with no clear clues as to their destiny leaving a cruel pain in the heart of their loved ones.

To Sehnaoui’s list of problems, Rima Mansour adds, through her acrylic and mixed media painting “Oppression,” injustice and oppression which are prevalent in so many places of the world.

In “Butchery”, a metal and ceramic sculpture, Nour Shantout wants to warn us overall of the acts of the internal monster that exists inside each one of us.

Many additional art pieces, each making a strong statement regarding peace and justice on its own, were also part of the show; they are, however, too many to mention here.

The SOS Art Liban exhibit was attended over an entire week by hundreds and hundreds of visitors who spent, for the most part, a long time viewing the art, reading carefully the artists’ statements. Many commented on the simple, unpretentious, respectful and egalitarian spirit of the show, also on how much they were touched and moved by the diverse messages of the artists.

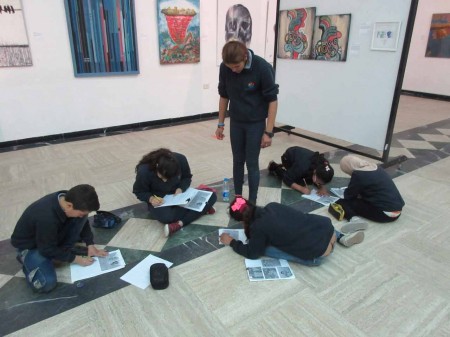

Some schools also brought their students to see and discuss the work, and in some instances met with the exhibiting artists. I was touched in particular by the students of school X, all 7 to 10 years old, who came one day to visit. They each had in hand already copied images of some of the exhibited works given to them by their teacher, with accompanying questions that they had to answer. The questions related to the artist, the medium, the content and message of the piece, also to their own views and reactions to the work.

They spent 2 hours diligently going from one artwork to the other, writing answers to questions, drawing. I learned later that they came from a very poor camp in the suburbs of Beirut and that they all live in very desolate conditions.

The festival of the arts of SOS Art Liban, which brought together many literary and performing artists, was also successful and very well attended. Poets read their poems relating to peace and justice, in both Arabic and French. Researchers, experts and thinkers spoke of poverty in Lebanon. 2 movies, one on the effects of the Lebanese civil war on society and one on the current issue of foreign domestic workers in Lebanon were screened and debated. A storyteller performed stories his grandfather told him about his youth in Palestine and his forced exile from there. Dance (classical and contemporary) and juggling/circus performances entertained both the young and adults; and people participated in improvised theatre based on memories and stories of the Lebanese civil war.

This first edition of SOS Art Liban would have hopefully achieved some of its intended goals, especially those of promoting the use of art as the voice of the artist and as a catalyst for change towards a better world. It is hoped that it will become an annual event and that it will expand further to actively involve art and artists in the daily life of their community, thus contributing to its betterment. It is also desired that SOS Art Liban become involved with school children and university students using and encouraging the arts as vehicles for peace and justice, and that it gets implemented in various cities and regions of Lebanon.

–Saad Ghosn

March 24th, 2016at 6:09 pm(#)

Saad, I am so moved by your introduction of this SOS Art project to Lebanon. Where the need to express is so profound, and essential to the well-being of the city and creative sector. Thank you for your continuing commitment to cultivation of artistic expression, and for your tireless work on behalf of the “makers” and the viewers alike.

March 26th, 2016at 12:16 pm(#)

Saad,

I am amazed at the range of work…from what we here would call “folk art” to some very sophisticated contemporary work. Too much to comment on here, but I was especially struck by the 12th grader Farouk Grissom’s shadow piece…what a melding of the physical and conceptual! Mycal El Khoury’s “The Screams of the Lacking Bodies” and Liane Mathes Rabbath”s “Dress of Hope” I also found quite moving. Will you do a book of this exhibition as you have done of the others? Will this continue in Lebanon the way it has here?

April 1st, 2016at 10:59 am(#)

saad- thank you for your tireless commitment here and abroad, especially given the difficulty of creating this again from the ground up. it is also sobering to see some of the similarities between cincinnati and lebanese responses to your call, and that most of us are simply striving for the same (basic) things.

April 8th, 2016at 10:00 am(#)

Dear Saad, Thank you for bringing this show to us through AEQAI. It is truly inspiring to see this work.

That it is embryonically attached to the Cincinnati SOS should put new resolve into local artists to participate in and nurture this important venue. A book of this work would be a beautiful and impactful learning tool not only in our community but in the entire U.S.A. Thank you, for everything.

April 16th, 2016at 11:17 am(#)

Thank you for taking me to Lebanon, for including me among viewers of these eloquent, beautiful and dreadful, creations!

April 19th, 2016at 9:43 pm(#)

Saad,

Thanks for sending me this introduction to your SOS community. It is a moving and beautiful collection of art. I look forward to seeing more of your SOS work in Cincinnati.

May 8th, 2016at 2:29 pm(#)

Good work. Good works. It humbles the Cinci artists to compare circumstances. Speaking truth to power is much easier in a land of plenty where the fight for (and over) a constitution ended long ago.

Helwa!