Hard Luck Honky Tonk showcases the devilish and defiant screen printing of Carlos Hernandez at Austin’s premier venue for the printed multiple, Flatbed Press and Gallery. Importantly, Hernandez has been synonymous with his shop Burning Bones Press in Houston, TX for six years now in partnership with one-time Flatbed Master Printmaker, Pat Masterson. Burning Bones is an impressive operation, one of the only professional printmaking studios in Texas that is fueled by its membership. It is at Burning Bones that Hernandez began the body of work featured in Hard Luck Honky Tonk.

Hernandez is one of the Outlaw Printmakers. He’s in love with Rock n’ Roll, and generally speaking he’s a very friendly person who does a lot for the printmaking community in Texas, and abroad. He’s an avid designer having worked for many different corporate clients. The roster of Rock n’ Roll acts that he’s worked for is similarly impressive. His clientele represents his dexterous ability as a designer, while his application to advertising of screen-printing brings a fine art element to the forefront of his production.

The focus of this exhibition is firmly rooted in a painterly shotgun blast of subtly seedy screen-printing evocative of the DIY ethos extant like a main vein throughout Hernandez’ oeuvre and professional practice. The exhibition’s main feature is comprised of five gargantuan monoprints. Monoprints are prints in every sense of the word. They are created through the physical act of printing. However, monoprints are singular in nature, irreproducible as they lack a consistent matrix, and tend to be thought of as the painterly approach to the craft. Hernandez began his experiments in large format monoprinting over the summer of 2015, and this exhibition became the impetus for their completion. Apparently Hernandez works well under the duress of a deadline.

Hernandez is a Graphic Designer and a Printmaker also, two halves of the same self married through the instant gratification of the silkscreened gig poster. While Hernandez expresses his love of Rock n’ Roll through his gig posters, he was quick to tell me that as far as he is concerned the posters are purely advertisements. He described the posters as informational attention injected with his creative flash. He does not hold a degree in printmaking, and started silk-screening show flyers fifteen years ago while he was in college. He described his process of those early days as a sort of throwaway style, purchasing a speedball screen-printing kit each time he needed to print a new poster. Once finished, it was all thrown out with the trash. Interestingly much of the found imagery that Hernandez’ uses in his work is redolent of beloved 1950’s clichés.

In Public Figure No. 3, one of the giant monoprints, the background is stacked with static rows of teenage yearbook photos from the 1950s, each youth clothed in cartoonish 4-H kitschery. Their eyes gleam with the promise of prosperity, smiles smeared across their faces; they are obscured by time, re-paraded for our regard. Overtop of these hopeful teenagers is a glowing calavera (skull associated with Dia des los Muertos) donning his finest western wear, sitting astride a pedal steel, the loneliest sound of the country music cavalcade. The juxtaposition is sinister, and absolutely typical for Hernandez. One of the other monoprints, Public Figure No.1, features a smiling woman, dressed like a socialite of the rodeo. Hernandez has painted her face with black stars of Peter Criss, the same black ooze dribbling down her dimples. Her breast is wreathed in ghostly shadow lilies recollecting homespun wreaths of old America. Her portrait is laid upon a background of Technicolor starlight, resonating nostalgic July Fourths gone past.

Hernandez’ M.O. is to repackage and regurgitate woebegone tropes from the Americana archive of pop culture iconography. Whether it be the propaganda sensibilities of the WPA era, the teengenerate emblemisms of punk, or the dire and dry lonesomeness of the Southwest, there’s a smorgasbord of carnival vibes to be felt, wrapped up in the bra-straps of B-movies.

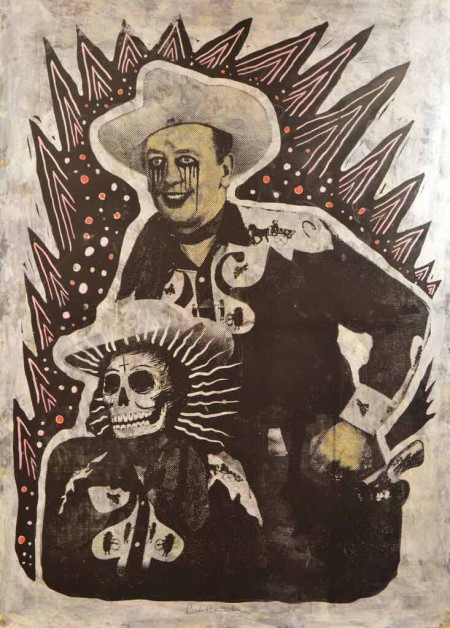

Country Before Country Was Cool depicts a spooky Man and Wife, seemingly a country music act. Her head however is swapped out and replaced with a calavera. His eyes drip with black ooze calling up Alice Cooper. The original picture is so awkwardly posed that the wife is left resembling a ventriloquist dummy. The print seems a little bit more tethered to Carlos’ poster printing.

Honky Tonk Hit Parade, another of the large monoprints, features another southern belle, six-guns double-crossed around her collar bones, her eyes and mouth drip with black ooze as she stares with crazy challenge into the space around. The title is printed around the brim of her cowboy hat and references the textual elements ever present in Hernandez’ rock n’ roll posters.

With this most recent exhibition Hernandez has ascended into a painterly permutation of his poster printing, where his love of country music, bona fide rock n’ roll, and counterculture are all evident as ever, but are freer, and graced with a new narrative context, one that reads more like a rockabilly liturgy and less like an advertisement.

–Jack Wood