Letter from Chicago: ‘Kerry James Marshall: Mastry’ opens April 23 and runs through September 25, 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. By Cynthia Kukla

If you haven’t met him yet, let me introduce you to Alabama-born, Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall. If you go to Los Angeles, you can see one of his major, large tableaux-style paintings that was purchased by the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art back in the early 90’s. That smart move by LACMA put Kerry on the map. He was raised in the Watts area of south-central LA, so this had to be very moving for him, getting professional cred on home turf. Were you at Documenta in 2007? Four of his Lost Boys paintings were in the Wilhelmshöhe Castle where the curators interspersed contemporary work with pieces in the permanent collection. Venice Biennale 2015? There was Marshall, featured with five paintings in the acclaimed Italian Pavilion, where the Venice Biennale Director selects all the work to be presented. Marshall showed the world how he interprets the Black experience in America: two of his standard figural paintings depicting common, everyday events in Black culture, like a man and woman hugging in the back yard. But being the Biennale, he had to ramp it up and he riffed on Richter with three sassy abstractions: More on that later. What a bold move that was! 1

Marshall states: “I decided you could only become free by entering into a relationship with art history by bringing an idealized form of your own image into that space and projecting that into the visual record with the same kind of power, with the same kind of force and same kind of inventiveness that drove that history of representation from a European perspective.”2

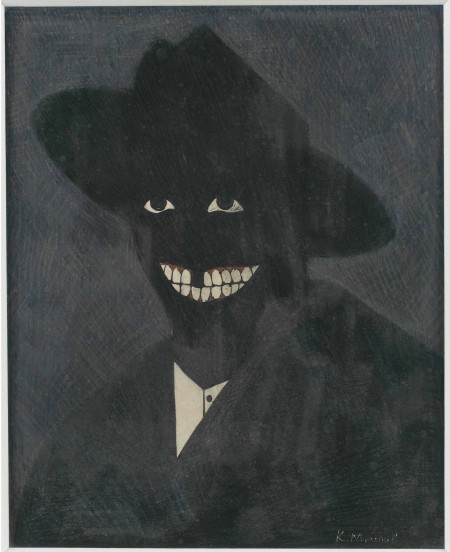

Let me expand on this quote. Marshall’s first significant painting after receiving his BFA from the Otis Art Institute in LA was a smallish egg tempera featuring a generic, sort-of-self-portrait. Painted in 1980, it is called A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self. It is brilliant because Marshall represented a black man with black paint. No shading. No blending of hues. Black is black. Pure black. This is one of several straight-up strategies Marshall has employed which I think have set him apart from other current figure-based artists. (The self-indulgence and privilege of Jeff Koons, Lisa Yusovage and John Currin’s banal white protagonists immediately come to mind; they contrast with Marshall’s bold use of pure black paint as cultural signifier.)

So began Marshall’s odyssey, building on this daring trope – representing a black man with pure black paint. Next up, some deadpan paintings like Portrait of the Artist & a Vacuum. This 63 by 52 inch painting featured a rendition of the aforementioned small self-portrait, which he painted onto the wall of the interior. The rendition of his self-portrait has a simple Hoover vacuum cleaner looming large in the foreground. Marshall followed Matisse, for example, by ‘quoting’ one of his own paintings, which he repainted within a new painting, just as Matisse quoted his own work in his famous Red Studio. The artist/vacuum cleaner painting also reminds me of some of the deadpan interiors and figures-in-interiors that Sigmar Polke did in the 60’s. Same angst, different era and continent; a statement on coping with the mundane, using the strategic political and aesthetic vernacular of the time.

MCA director Madeleine Grynsztejn states: “We’ve seen his work over the years episodically-a small show here, a big group exhibition there and this is a moment where we need to see this extraordinary body of work in one place and have the privilege and exciting opportunity to assess in visual terms some of the most urgent issues of our time.”3

Kerry James Marshall’s sweep is enormous, embracing the figural vernacular and, as seen in last year’s Venice Biennale, he takes on large abstractions as well, which was a surprise and a confident throw-down with Gerhardt Richter.

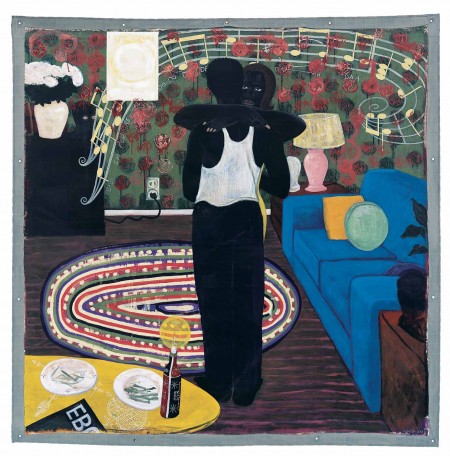

Kerry James Marshall’s vivid, lushly painted and inventive narrative tableaux comes from his early life in LA, then his move to Chicago – in his Bronzeville neighborhood – and in his constant awareness of the African-American experience of which he feels there are few masterful art representations. When Marshall spoke to us at the press event, he repeatedly underscored – for him – his acute awareness of the lack of black artists whose voice was mainstream, who stood there as guides for him, as a young black artist embarking on his path. Certainly I think that Romare Bearden set a good path for him to follow, along with the Ashcan painters and regionalists currently getting their due (Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood.) Gordon Parks did the same for artists of color in photography.4 It’s Marshall’s particular combination of painting the authentic blackness of blacks in authentic settings (unlike Kehinde Wilde who borrows Baroque Eurocentric-poses and backgrounds for the young Blacks he represents) and infusing his large tableaux with circus-poster or local muralist elements like text banners and local collage elements, that gives Marshall’s paintings their authenticity and originality.

So there are three elements I determine that give Marshall such bite, freshness and authenticity of voice: one, the bold trope of using pure black paint to depict black people, two, the use of historic circus and carnival-style text banners (where I imagine Marshall observed in the historic genre the racist separation between white and black performers and the dramatic representation of racial types) and the use of local collage elements from historic black texts, local palm reader pamphlets, and such to further authenticate his paintings’ narratives. With all of this in hand, his paintings give us the past and the present of the Black American experience at full volume.

And he does it without anger.

This theatricality is present in De Style, the 104 x 122 inch painting from 1993 that LACMA bought. Three men are getting their hair done, one sitting in the barber’s chair with the barber behind him. The other two men have their crazy, outlandish dos finished. Their dos are pure sci-fi, the one on the left has an up-do that keeps going up up up (rather like Marge of the Simpsons.) The man on the right has his do curving and flaring out above his head. The men are all stylish, the barbershop is stylish and the setting is a place of both power and community.

My favorite painting in the show is hung opposite De Style and is its companion. It is School of Beauty, School of Culture from 2012. It’s woman power to match the man power of De Style. Women beauty school instructors, and patrons and students that include two men in the salon chairs, are all at work or being worked on in the beauty school. Someone’s two toddlers occupy themselves in the foreground. So what is the big deal? OK, first up, is the large anamorphic rendition of a blonde white girl in the center foreground which screams Holbein’s ‘The Ambassadors.’ It is hilarious. Not a skull, a Renaissance reference to the soberness of life and death, but an anamorphism of a white, blonde-haired girl-the ideal to which many in society aspire. In his talk, Kerry said, “Just like the skull haunts Holbein’s audience, so the contemporary black is haunted by white standards of beauty as exemplified by a blonde.” A black toddler bends over and attempts to peek under the anamorphism. But that’s not all! Improbably, this beauty school has a fine poster of Chris Ofili’s show at the Tate Modern (London) featured on the wall. Other posters and sly references to Black culture, like singer Lauren Hill, are there too. The painting of the beauty school interior jumps with Black attitude and it is fun. The composition is brilliant. It’s Stuart Davis and Romare Bearden at their very best for a new time. Marshall wanted to do the beauty school painting after the success of his barber shop painting which was his first museum sale, because these establishments are considered key places of community in black neighborhoods.

In a 1998 interview with Bomb Magazine, Marshall observed, “Black people occupy a space, even mundane spaces, in the most fascinating ways. Style is such an integral part of what black people do that just walking is not a simple thing. You’ve got to walk with style. You’ve got to talk with a certain rhythm; you’ve got to do things with some flair. And so in the paintings I try to enact that same tendency toward the theatrical that seems to be so integral a part of the black cultural body.5

Get up to Chicago now! ‘Kerry James Marshall: Mastry’ opens April 23 and runs through September 25, 2016 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. There are over seventy paintings spanning a thirty-five year arc. After the Chicago debut, ‘Mastry’ travels to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Met Breuer, in New York, from October 25, 2016 to January 29, 2017. The exhibition concludes at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles from March 21, 2017 to July 2, 2017. Both venues also served as co-organizers. The stunning 280-page color catalog by Skira/Rizoli is developed by all three museums and is a most worthy addition to any serious art enthusiast’s collection of monographs.

All images courtesy of MCA Press Office with exception of photograph of Marshall at press opening, and Blob, both taken by author.

Cynthia Kukla is an artist living in Illinois and emerita professor of art (finally).

1http://aeqai.com/main/2015/09/la-biennale-di-venezia-part-two-americans-in-venice/

La Biennale di Venezia: Part Two: Americans in Venice

September 21st, 2015

2MCA Press Office.

3Ibid.

4See article The Art of Gordon Parks (Retrospective) at http://www2.cincinnati.com/freetime/weekend/021601_weekend.html

5Reid, Calvin. “Kerry James Marshall”, ‘’BOMB Magazine’’ Winter, 1998.

May 25th, 2016at 4:07 pm(#)

I think your assessment of the artist Kerry J. Marshall’s work is quite incisive. I also agree with your placement of “School of Beauty” as the best in the pictures that accompany your article. The “emerita” photograph is very attractive.