Photographs by James Friedman of 12 Nazi concentration camps opened in October 2016 at the Cincinnati Skirball Museum at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in partnership with The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education. The photographs are on view through January 29, 2017.

The Columbus, Ohio resident traveled to Europe in 1981 and 1983 to photograph in color Nazi concentration camps in Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany and Poland. His interest originated from the time he was four when he saw his family’s dog hung outside because they were Jewish. More anti-Semitic events followed: his family’s house was set on fire, but they didn’t move.

Survivor of three Nazi concentration camps, survivors’ reunion, Majdanek concentration camp, near Lublin, Poland, 1983

Photo by James Friedman

The memories lingered with Friedman and emboldened him to draw attention to the Holocaust with his pictures. He served on the faculty of the Ohio State University. In 1981, he received a grant from The National Foundation for Jewish Culture to the Ohio State University Gallery of Fine Art to travel to Europe for a pictorial review of concentration camps. He returned to Europe, specifically Poland, to visit three camps and complete his photographic study in 1983.

When Friedman visited the camps during the Cold War, there was nothing left in many of them but a field or memorial sculpture or fabricated barracks to replace the ones that had disappeared. In other camps, the effects of tourism had left their mark, according to Abby S. Schwartz, director, Cincinnati Skirball Museum.

“I intended these photographs to be audacious and surprising and, ultimately, impossible to forget. I hope they will challenge viewers’ ideas about the camps and what happened there by presenting the past and present simultaneously,” Friedman said. With these images from 12 camps, he addressed lingering emotions and confronted memories. Auschwitz, in particular, was virtually intact and haunting.

“My color photographs include self-portraits, tourists and survivors,” said Friedman. “They exist in stark contrast to the black and white photographic record of Holocaust.” These are considered primary documentary photographs. In his exhibit, Friedman includes several such as one by Margaret Bourke-White, noted American photographer (1904 – 1971).

He elected to use color photographs taken by a 8” x 10” field camera. He made no attempt to travel back in time. Rather, they are unsettling and startling, as hallowed ground collides with modern reality.

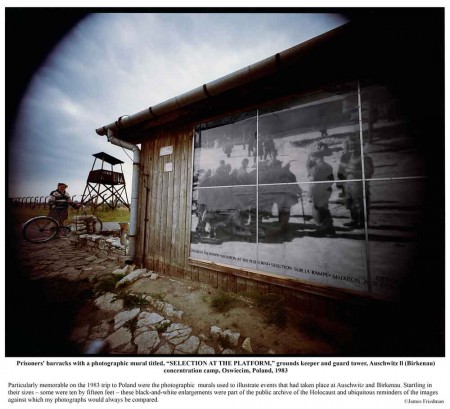

Friedman pointed out several significant photographs in the exhibit. They include a local resident with a scythe, a survivor, the survivors’ reunion and prisoners’ barrack. See accompanying pictures.

In one photograph, a teenager uses a parking lot at Dachau to run a remote-control toy racing car. At Mauthausen, a truck delivers colorful cases of soda to the concession stand. In others, Friedman inserts himself into the landscape or poses for the camera.

“My color photographs include self-portraits, tourists and survivors, and have inspired visceral responses in many viewers,” said Friedman.

“The pictures are, inscrutably, both objective and subjective. They are against the grain, self-reflexive and idiosyncratic in breaking new ground in the medium, while at the same time acknowledging the tradition of documentary photography,” he said.

Schwartz said she was approached by a Columbus friend of Friedman to take a look at his photos. “I was so stunned,” she said. “They were in color, pristine and used a transfer dye,” one of the most permanent and stable processes in photography, according to Friedman. He said that the dye process is no longer available. Schwartz was convinced to mount an exhibit.

“My wheels began turning,” said Schwartz. “It needed to be used as a springboard for learning to interpret the Holocaust from May 1945 when the camps were liberated. How will we look at this period of history? Will it be the camps? Some sites are in good repair; some are not. I brought in Sarah Weiss, executive director of The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education, to brainstorm. The center produced a gallery guide. And, public programs were developed.”

Schwartz partnered with several organizations and people to complement the exhibit. For example, The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education offers Through Their Lens: Photo Reflections on the Holocaust, showing photos taken by local students, teachers and the general community at Holocaust sites. This exhibit will run through January 27, 2017 at 8401 Montgomery Road.

Other public programs were offered in conjunction with this exhibit. An opening reception on October 13 featured Rabbi Jonathan Cohen, dean, Cincinnati Campus of HUC-JIR; Abby Schwartz; James Friedman and Sarah Weiss, executive director, The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education.

Lunch and Learn with the Artist was held with James Friedman on October 26.

Holocaust survivors Michael Kraus from Brookline, Massachusetts and Frank Grunwald from the Indianapolis area endured Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps. They both expressed their experience through art: Kraus through sketches and writing and Grunwald through drawings and film. On November 16, Kraus and Grunwald shared their stories of survival and art as resistance before, during and after the Holocaust.

On December 7, panelists Dr. Brett Ashley Kaplan, Dr. Gary Weissman and James Friedman discussed the issue of how popular culture has shaped Holocaust memory. They explored the ways in which music, the media, photography, television and the performing arts have addressed the subject of Holocaust memory.

Skirball itself partnered with its core exhibition An Eternal People: The Jewish Experience. Featured works are examples of both primary (survivor, perpetrator, liberator) and secondary witnessing of the Holocaust. Like James Friedman, those who are secondary witnesses did not personally experience the events of the Holocaust, but respond to its horrors through a variety or artistic expressions. Artists include Linda Giesen, Dr. Siegfried Emmering, Greta Schreyer, and Alice Lok Cahana.

The final event is a closing reception on January 29 from 1:30 – 3:30 p.m. It is also a commemoration of International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The United Nations General Assembly designated January 27—the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau—as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. On this annual day of commemoration, the UN urges every member state to honor the victims of the Nazi era and to develop educational programs to help prevent future genocides. In Cincinnati, guest speaker is Senator Mark Leno, the first elected gay man to serve in the State Senate of California and former vice mayor of San Francisco. The lecture is free and open to the public.

“Since I was five years old, I have been photographically curious about people, places and events in my life,” Friedman said. “As I became older, I took photographs of my family, friends, relatives, celebrations and losses that became reminders of my personal history. Eventually, I decided to dedicate my life to documentary photography and understood that, as a maker of pictures, I was in the memory business.”

Friedman taught himself photography until college when he participated in the Ohio State University Honors Program and earned a BFA degree with distinction in photography. At OSU, he became interested in the art of secondary documentary and witnessing of the Holocaust. He furthered his education with an MFA degree in photography from San Francisco State University.

As a teacher, curator, picture editor and photographer, he has enjoyed a wide-ranging career. His work has been exhibited internationally and published in major newspapers such as The Boston Globe and The New York Times.

Friedman has received many awards including the Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award in Photography in 2015, 2009 and 2006. In 2011, he received the Governor’s Award for the Arts in Ohio, honoring an individual artist whose work has made a significant impact on his discipline.

Because of his body of work, Friedman is known nationally as a top flight photographer. The Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, represented him from 1988 – 2002.

Although he taught photography from 2001 to 2003 at Santa Fe Community College, he returned to Columbus to continue his work. He wanted to get out of the comfort zone of academia and address the anti-Semitic issues which had faced him and his family. “You can’t take my art away from me,” said Friedman.

The exhibit takes place at the Skirball Museum in Mayerson Hall, Hebrew Union College, 3101 Clifton Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45220. Hours: Tuesday and Thursday 11 am – 4 pm; Sunday 1 pm – 5 pm. Free and open to the public. Up to 1,000 visitors have seen the exhibit to date, according to Schwartz. FotoFocus Biennial 2016 provided support for this exhibition.

“James Friedman’s 12 Nazi Concentration Camps is arguably the most significant body of photographic work on the concentration camps in the post-Holocaust era,” according to Dora Apel, Ph.D., chair, Modern and Contemporary Art History, Wayne State University.