Throughout my youth, my mother dragged me to more museums than I wished to attend. But in doing so, she instilled in me an understanding of art’s capacity to impart change. Works by artists such as Barbara Kruger, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat didn’t just inform me about pressing issues of the time, but they prompted me to pause and contemplate such from a critical perspective.

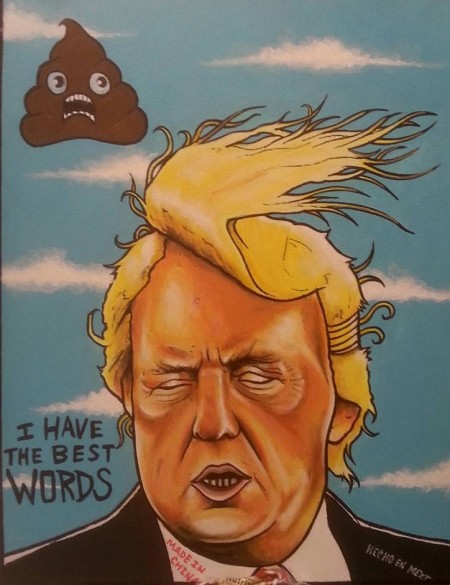

Perhaps most influential were Robbie Conal’s posters that started popping up all over Los Angeles in the late eighties. I was in high school at the time and my father lived neared Melrose and La Brea, a corner commonly plastered with the artist’s satirical portraits. As a teenager, I was much more attuned to trends in fashion and music than politics. But Conal’s portrayals of Ronald Reagan and Oliver North, among others, prompted me to start questioning the actions of our elected officials.

Since November 8th, I haven’t only had trouble reckoning with the reality that Trump will soon be in office, but I’ve had trouble reckoning with the reality that so many of our country’s citizens continue to lack the capacity to critically examine the platforms of those they choose to put in office.

From experience, I know that my aptitude to question rather than accept any suggestion put forth stems from my exposure to the arts. Works like Picasso’s Guernica and Duchamp’s Fountain are what inspired me to start asking questions from an early age. Even more, they are responsible for providing me with a wealth of understanding that I wouldn’t have gained had I never been given the opportunity to witness them. Therefore, I can’t help but to assume that the cuts to arts education in our public schools over the last four decades is one reason of significance that explains why so many voted for a man who has virtually no political experience.

According to Fran Smith, author of “Why Arts Education Is Crucial, and Who’s Doing It Best,” years of research have indicated that arts education is “closely linked to almost everything that we as a nation say we want for our children and demand from our schools: academic achievement, social and emotional development, civic engagement, and equitable opportunity.” Since the 1970s, however, arts education programs have continued to experience devastating cuts. While no one can deny the benefits that the study of math, science, English and history can lend, too few seem to acknowledge the real value that art, music and theater can have on curriculum.

After a series of reports conducted by James Catterall was published in 2012, Rocco Landesman, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, concluded that “the chance for a child to express himself” has long been lost after so many years of cutbacks. But still, nothing has been done despite our access to quantitative proof that speaks for itself: “students who have arts-rich experiences in school” don’t only excel academically, but they tend “to become more active and engaged citizens, voting, volunteering, and generally participating at higher rates than their peers.”

In her essay, “Why Americans Are Afraid of Dragons,” Ursula Le Guin explains that “we tend, as a people, to look upon all works of the imagination either as suspect, or as contemptible…. In the businessman’s value system, if an act does not bring in an immediate, tangible profit, it has no justification at all.”

This makes sense, given that we live within the confines of a capitalistic society. Thus, it is understandable why so many feel that teaching a child to paint or play the trombone is indeed unnecessary, unless, of course, she can demonstrate some sensational talent, worthy of monetary compensation.

But this isn’t Le Guin’s point. Rather, she argues that in order for each one of us to mature completely and deepen our understanding of the world, we must have experienced ample opportunities that indulged our imaginative tendencies throughout our formative years: “all the best faculties of a mature human being exist in the child, and that if these faculties are encouraged in youth they will act well and wisely in the adult.” Unfortunately, however, “if they are repressed and denied in the child they will stunt and cripple the adult personality,” which is sadly what our school system appears to have done.

While fighting for the inclusion of arts education in today’s public schools seems a low priority, given our president elect’s growing agenda which, in one big swoop, is threating to undermine all the progress that we have made regarding the rights of minorities, women and other marginalized groups, I still have to question the efficacy of our public school system, given the fact that it was initially established on the assumption that a functional democracy is reliant upon an educated citizenry, adequately schooled in the liberal arts.

–Anise Stevens