Listening to a college radio station on my way to Blaffer Art Museum, I heard the song “The American Dream” from the musical “Miss Saigon.” You know—the one with the helicopter, wherein a Vietnamese prostitute is impregnated, and then abandoned, by an American GI. Pieces like “Miss Saigon” are pervasive in the west’s perception of Vietnamese culture: rooted in war nostalgia with a healthy dose of stereotypes.

How funny to hear this song on the way to see an exhibit by the Propeller Group, an art collective dedicated to elevating the Vietnamese voice on the international scene.

The Propeller Group is a Ho Chi Minh City and Los Angeles-based art collective led by founders Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Phu Nam Thuc Ha and Matt Lucero—but it is also a functioning advertising agency. I’m reminded of Banksy’s quote about how this generation’s best artists are wooed into advertising for the salary: the Propeller Group supports that claim, not only because they’re great artists, but because of the initial goal of a steady income.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen said as much in a discussion on June 3 at Blaffer, one of many educational events that will be held in conjunction with the exhibit this summer. Here’s a paraphrased version of his reply when asked whether the group felt it was their responsibility to confront communism, war and commodification, or if it was more of an opportunity:

Going into advertising was more of an opportunity, not a responsibility. It put food on the table. But it also gave us space to explore ideas. At first, we were really bad advertisers. But learning how to send messages through images, through an advertising lens, has changed the way we make art, and the way we use images to communicate. What’s funny is that we all grew up in Los Angeles doing graffiti, destroying billboards, the very things we now create. We’ve come to feel comfortable with confusing people—both ad agencies and museum curators. Sometimes it means we don’t get a show, and that’s okay.

The exhibition’s centerpiece, a 20-minute film called “The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music,” is a prime example of those dichotomies. If I told you it was a short documentary exploring the funereal traditions of Vietnam, this film is not what would come to mind. Yet that’s what it is—except shot as a music video. As Tuan puts it, they made a video with the people, not about them. A “music video” is such a commercial thing, designed to sell a band. The result is less “selling” than “art,” but thinking of it as a music video instead of an examination brings a whole new mindset to the act of learning about a unique culture. It takes out the exoticism and lets it be purely fantastic.

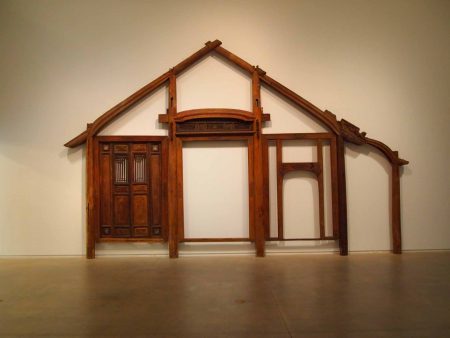

Thanks to the Blaffer’s curatorial efforts, we’re prepared to see this video by the first two galleries. In the first, a shorter film (on a mounted TV set with a few pairs of headphones) plays a conversation between a Vietnamese artist and a FedEx customer service representative: the artist’s Dutch relics have been lost. Throughout the course of the conversation, the representative convinces the artist that he should be using the work of his own country to represent it. The visuals do not show the speakers, only Vietnamese men loading up trucks with the artwork. It’s fitting that this is directly across the room from the intricately carved framework of a Vietnamese structure.

Here, we also see a poster for “AK-47 vs. M-16,” the group’s 45-minute feature film that will be shown weekly in the museum throughout the summer, using these two models of machine guns as their protagonists in a characterization between the east/west war machines. Above, flags championing a rebranding of communism wave. The rebranding featured heavily in the lecture discussion: the group actually approached the advertising agency TBWA\Vietnam to rebrand communism, and made a documentary about the meeting that ensued. Only the flags are present here, but the irony of putting a brand on an expressly anti-capitalist ethos is beautifully snide.

Next, we see a stripped-down motorbike: a Honda Dream. A video shows the bike when it was intact, parked on a street: throughout the night, vandals strip it down to its frame. Motorbikes are ubiquitous now, but prior to 1995, bicycles were the main mode of transportation for the majority of citizens. After Vietnam opened to international trade, Japan was one of their first partners, the Dream one of the first big imports. Prohibitively expensive for most at first, it was a literal dream to be able to own one. Then, since so many owned them, a secondary market for stolen parts boomed. Dream, indeed.

The soundtrack to “The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music” pervades throughout the first floor gallery to great atmospheric effect. The film itself is an exploration of Vietnamese and New Orleans death rituals, with the swampy delta landscapes and diverse musical numbers evoking the landscapes and soundscapes of both continents. Death is a celebration in this film, not an ending: the journey continues forever. The camera is in constant motion, with groups of people acknowledging it, but not enough to stop their daily life, or to discourage daring feats (snake charming, sword swallowing, playing with fire)—such is the way the promise of death hangs like humidity, and people live spectacularly through it.

“Untitled (Ox Head: The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music)” by the Propeller Group. The water buffalo is an important symbol in Vietnamese culture and a sign of good fortune; this skull is featured prominently in the film as a costume piece.

Lest we forget about war in the joviality of “The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music,” the second film, “The Guerrillas of Cu Chi” comes with a warning: “Adults may wish to preview this video before viewing with young children.” In the theater, two screens stand parallel about 15 feet apart. One is a black and white propaganda film from the Vietnam War era, with a woman’s Vietnamese-accented English narrating the beauty and destruction of Cu Chi, where the Vietcong’s hidden tunnels are now one of the country’s biggest tourist attractions. The other screen documents one popular part of the attraction: visitors age 14 and up can pay extra to fire mounted AK-47s and M-16s on a shooting range. In slow motion, smiling tourists pose for photos and shoot, with a slow, long blast echoing through the other film’s narration.

You, the viewer, are the target. The effect is chilling, and the parallel screens add another dimension: we literally have to choose where to look, which truth to acknowledge. The Propeller Group draws our eye the way that only marketers can (“The American Dream” pops back into my head) without losing the conflict that good art requires.

The Propeller Group exhibition runs through September 30, with a series of educational events and showings of “AK-47 vs. M16: The Film” throughout the summer.