This fall, two special exhibitions among the vast collections at Wellesley College’s Davis Museumare especially worth the 20-mile drive from Boston: Eddie Martinez’s “Ants at a Picknic” and “Life on Paper: Contemporary Prints from South Africa.” These shows are opposite in a few ways: one featured artist versus many, painting on a large scale versus intricate printmaking, art explicitly as autobiography versus a collaborative medium. It’s only the exuberant mastery bursting from each that connects them. Together, they are the highlight of the fall semester at the Davis Museum, and not to be missed.

From left: aerial view of “Mandala #7 (Frankenthaler Wash),” “Mandala #8 (Ants at a Picknic),” and “Mandala #9 (Untitled)” by Eddie Martinez (all 2016)

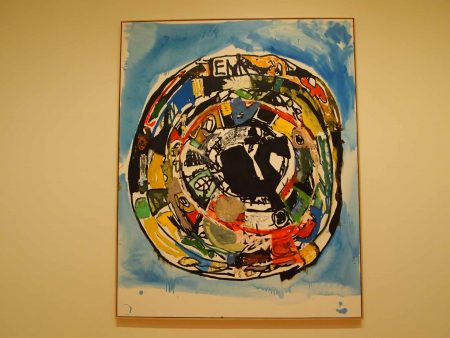

“Ants at a Picknic” marks the first solo museum show for Martinez, a Brooklynite whose diverse inspirations include the COBRA artists and skateboarding culture. The exhibition’s title is the same as one of his large mandalas: seven fill one gallery, each roughly five by seven feet. He created each mandala from a small drawing, blowing it up to full size in a flatter black silkscreen ink, then filling it in with oil paint, spray paint, and other varied materials, including scraps of fabric and baby wipes. He explained in a 2016 interview: “I was in a state of turmoil and got obsessed with the amount of trash I was producing. And so I just started sticking it onto the canvas.” The result is wonderfully textured and engaging abstraction.

Calling these pieces “mandalas” is significant: they are quite literally microcosms representing the artist’s inner thoughts and, as he describes it in his statement, compulsive attitude toward drawing. They quite literally represent his world, as a mandala traditionally represents a microcosm of the universe. I thought of the Buddhist practice of sandpainting mandalas, a painstaking process of meditation which is then, like all human endeavors, easily swept away. Afterward, I learned that Buddhist monks from Ithaca, NY actually had had a three-week residency in conjunction with the exhibition—the timelapse of the creation and destruction of their mandala can be viewed here. An interesting connection and educational opportunity, although Martinez’s mandalas are a bolder, more permanent record of his artistry.The smaller adjacent gallery holds smaller, but still sizeable, drawings and about 20 tabletop sculptures, each reflecting Martinez’s penchant for found objects—although in his case, the “found object” is often his own drawing. Many of thebronze sculptures repeat themselves down to the smallest detail, with color being the only difference.

“Life on Paper: Contemporary Printmaking from South Africa” occupies a much smaller space in a hallway connecting two galleries on a different floor. If one was particularly excited about reaching the Martin Luther-inspired print exhibition, it would be easy to skim right by. That would be incredibly unfortunate, though, as the scope and history of these prints are a testament to the country’s artists and acknowledgement of art as a means of social justice and expression—and just plain cool.

“Living Language (Cat)” (drypoint, 1999) by William Kentridge. Known for his work across media, Kentridge treated language instruction records as printing plates in the “Living Language” series.

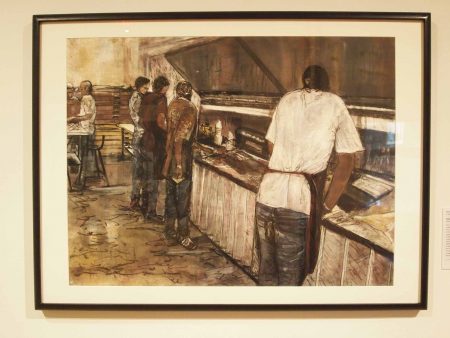

During the Apartheid years, printmaking, with its flexible formats, portability, relative affordability, and collaborative nature was a catalyst in the exchange of ideas and the articulation of political resistance. The Artist Proof Studio (APS) in Johannesburg co-sponsored the exhibition, and its co-founder, Kim Berman, has a piece in the exhibition that records the studio’s commitment to printmaking as an egalitarian medium: “Telling the Story: Students at Work I.” The central ethos of APS is ubuntu, a Nguni belief that “a person is only a person because of other people.” This not only underscores the often collaborative process of printmaking, but the way that change takes hold when people work together to fight injustice.

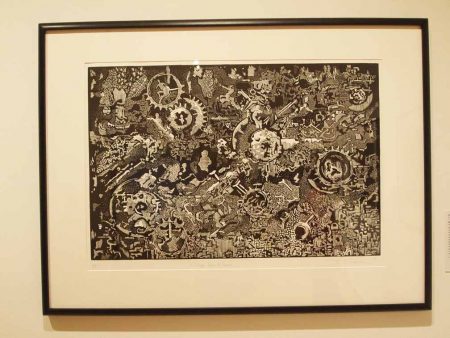

Lucas Nkgweng, a former APS student, is now one of its longest-serving staff members, and his etching “Life is a Grind” marks a move toward abstraction after a history of producing social justice-centered works. Instead of just using needles to mark the copper plate, he used drill bits, wire brushes and sanding machines to “grind” new shapes into the print. Speaking of a daily grind, Susan Woolf’s “Taxi Hand Signals” colorfully captures one unofficial addition to South Africa’s 11 official languages: gestures that represent a pedestrian’s destination, thereby hailing the appropriate mini-bus. Woolf is also an anthropologist, and has spent a decade researching the hand signs, which are typically only used by the working class—and users often only know a few. The brightly colored gloves denote Bishop Desmond Tutu’s description of post-Apartheid South Africa as a Rainbow Nation. The work is also available in booklet form as a resource for locals and tourists alike as an equalizing educational tool.

The print that reminded me most of the Eddie Martinez work I had just seen was the linocut “All Things Began To Happen” by David Tsoka, a 25-year-old artist. That’s less because of its appearance and more because the artist regards it as “the journey of life,” drawing inspiration from large-scale sculptures and comic book onomatopoeia. Blobbed figures subtly populate the bombastic yet precise galaxy, some floating in womb-like spheres, some confronting jagged shapes head on. Measured in foot-long smears of oil paint or millimeter-wide etching, the journey is long and satisfying at the Davis Museum this fall.