Editor’s Note: Aeqai is pleased to republish Megan Bickel’s interview with Gibbs Rounsavall. The interview was originally published on Five-Dots.

Gibbs Rounsavall compares his studio practice to that of a scientific exploration embracing the thrill of discovery. The focus of his study has primarily been on relationships between shape and color. One of his bedrock principles as an artist is that color has such strong associative powers that it can transport us through time: eliciting memories while simultaneously suspending the perception of reality. Although his paintings may appear computer generated, all work is hand painted and drawn, with a closer look revealing faltering lines and imperfections. This is a reflection of his own capacity for self-awareness in the moment where an impulse to make a specific kind of mark reveals itself.

After attending Washington University in St. Louis, Gibbs hopped around to Columbus Ohio, New York City, and eventually back to his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky to receive his Masters in Art Education. The whole time he was making work, showing work, and meeting other artists. He began teaching in New York for L.E.A.P. (Learning through an Enhanced Arts Program) where he developed his own visual art curriculum with the objective of using art to teach literacy skills. This program influenced his decision to pursue his Masters in Education and so he came back to his hometown, Louisville. He’s been here ever since.

Five-Dots: How long have you been in this studio?

Gibbs Rounsavall: We bought the house about ten years ago and one of the big reasons we purchased it was because of this space; which actually used to be a mechanics’ garage. We saw a lot of potential in the space. We’ve put some money and time into it and now I have the loft space above, we’ve installed an HVAC system so that it’s climate controlled, and above all, it’s at my house. The space is pretty raw, but it’s worked out great. I’ve had studios that weren’t at my home and they were great experiences, but this way I get to live with the work. I work at a relatively slow speed so having the studio on my property allows me to work in a lot of small sections of work time into my day. I’ve been in this studio pretty much since we moved in.

F-D: When you moved in here, did you have an idea for how you wanted to lay it out or did it develop organically?

GR: Yea, I had ideas. I still have ideas. I’d like to put in some sky lights and all of that; but we have some walnut trees that could be a potential hazard. It’s been a slow process: framing it out, throwing up OSB, and getting florescent tracks in here. It happened organically over the ten years that I’ve been in here. Now it’s like a second home: it’s very comfortable.

F-D: Has the location of the studio (i.e the neighborhood, city, building etc) influenced your work in any way?

GR: I’m sure they have. My last studio was downtown, where Impellizzeri’s is currently. The studio was about ten thousand square feet. I had the whole bottom of that space to myself.

F-D: How did you acquire that?

GR: My brother-in-law owns the building. That’s how that happens; to be frank. He had approached me and said that he didn’t have anyone in the building and if I wanted to work there I could. So I did. I started making large paintings because of it’s spaciousness. It’s the old adage that the ‘space dictates the work’. That was a great space. It was obviously very different from my current arrangement: my studio is now in my home and I’m in Crescent Hill. Overall, I’d say I really enjoy my location. On a Saturday or Sunday I’ll take a break and walk down to Frankfort Avenue and grab a coffee. I’m near the public library. It’s kind of quiet, but it’s urban enough to where I don’t feel like I’m stuck out in the middle of no where. It works well for me.

F-D: Can you describe a typical day for yourself, inside the studio and out?

GR: I get up around five everyday. Then I alternate days; I either run in the morning or I come out to the studio. I’ll work for about an hour. Then I go teach until about 2:30 and then I come back and work for about an hour and a half. Then I have my family time, kids coming home from school and what-not. Then sometimes at night I’ll come back out to the studio. If I’m lucky I’ll get three good hours a day. I’ve learned over time that you don’t have to work eight hours in the studio every day to get good work. Really, for me, I’m going to get three or four hours and then I need to stop after that. I need to walk away and recuperate. Then I need to be away. You need that distance to be able to come back and be refreshed.

F-D: How would you describe your subject matter or the content of your work?

GR: I’m working with pretty basic elements considering that I’m working non objectively. A lot of my work is focused around exploring human experience and approaching it on a visual level; studies in visual perception, if you will. So when I started working minimally like this, years ago, I was really just interested in teaching myself how to use color well. I’ve always had an affection for color. I started with stripes. Then that kind of evolved. The potential is infinite with color. I don’t feel like I need to muddy up the surface with a narrative or something topical that might not be relevant tomorrow. I feel like the kind of stuff that I’m working on now is timeless. It’s universal. I’d hope that someone from Kentucky can appreciate it as much as someone from Kenya. We all have associations with color: cultural, personal, whatever they may be. It just reaches across all aisles.

F-D: Given your interest in color perception; do you think that you are intentionally being open ended for the viewers’ projection, or are there self-historical elements that are influencing your decisions?

GR: Well, being a minimalist kind of implies open ended-ness, but I do have some deep personal associations to color. I grew up in a very colorful house. My mother was kind of over the top with color, like, florescent colors, patterns, and wallpaper that was intense to the eye. So, in some respects this is a comfort to me. It reminds me of home. Vibrant color has an energy to it. The last show that I had at Hyland Gallery was a very different kind of show for me. The palette was very muted and so I really had to soften it a bit. That was a nice, short tangent for me. But I always come back to working straight out of the tube.

F-D: What mediums do you work with?

GR: I work with 1 Shot enamel paint. Which is an industrial paint. I started working with it in New York after a friend of mine exposed me to it. Sometimes I’ll go back to acrylic. I’ve never really worked with oil. I love 1 Shot; the color is great, the consistency is wonderful, it self levels. . . It’s good stuff. Oh, and painter’s tape. Lots of painter’s tape. 3M sent me a free box of tape once because I was buying so much tape, so that was a fun surprise.

F-D: Can you tell us about your process and how it has evolved?

GR: I honestly don’t feel like my process has changed all that much. Like I mentioned before, I feel like I’ve become more efficient. I don’t know. . . it has evolved in that I’m ok with a lot more than I used to be. I used to be kind of crazy about stuff. I’ve calmed down a great deal. I’ve embraced being as painterly as I can be painterly. What I mean by that is: I’m ok with the lines not being super precise. In fact, I kind of embrace that. I like that it’s a little wonky. It shows the humanity. I’m not trying to hide that I’m a person making these things. I like the idea that they look super detail oriented, but I also like that you can see that it was made by a human hand.

Having children changed my work. I like to make work that requires a great deal of time, that investment of time has always interested me. Before I had my kids I had that opportunity to sit back and ponder and articulate. Now that I have them, it’s more about how I can utilize small windows of time more efficiently. I just make quicker decisions and I rely, and trust, my instinct more. They’re incredibly influential on my studio practice and work process.

F-D: Do you work with narratives, plot, or any general progressive ideas?

GR: Color is something that I always come back to and work in and with in a variety of formats. The circle came into my life and kind of dominated for a while. From a design standpoint, the circle has always held my attention. When you work in a square / rectangular format it reads as a book or television. [In the west] we are used to reading things from left to right. When you work with a circle there are no corners: there’s nowhere to hide. The design needs to be really well thought out; but at the same time it’s also more natural. The circle speaks to nature and the universe. We have a more emotional connection with circles, I think. I’m possibly returning to the rectangle because my engagement in wanting to making paintings has come back, rather than wanting to make paintings that somehow exist outside of that lexicon: such as paintings as objects. I’m back to wanting to hang something up on the wall, so that we can see what comes from the experience of looking at that thing on the wall. These two are a part of a series that will bring to question what happens when painting enters that third space. This is something I’m excited about (points to multidimensional panel). They will exist on multiple walls and ceilings, they will come down to the floor, they’ll hang on the ceiling. It’s more immediate, and it’s a different way to engage with the work. It exists in our space, rather than being propped up to exist in our space.

F-D: That’s an interesting evolution, where do you think that idea evolved from?

GR: It evolved from a conversation I had during a studio visit. We started discussing this work here (points to large rectangular painting) and I had just read The Doors of Perception, (Aldous Huxley, 1954). I was explaining that I wanted these paintings to be easier to enter, to be more accessible. I wanted them to be on the floor so that they could become something that you could slip into, something that you could fall into. Then I thought, well, what if there was a sense of time involved. It just didn’t live here (pointing to the wall) or there (pointing at the floor); it would have to live in both worlds. It appears like it just fell. You’re catching it there visually. I love that idea. I love that the viewer gets to witness something kind of special. An accident in a painting.

F-D: Do you consider your work to be autobiographical at all; does personal history work its way into your making?

GR: Personal history definitely does. I see certain shades of color and it takes me places. It’s probably why—and I say probably because it’s still under investigation—I have such a strong visceral reaction to it. Somewhere down the line some synapse clicked and I have all of these associations with color and I can recall things just by using a dark magenta. So, yea. I mean. . . My Little Pony is all over this painting, in reference to my daughters. So, yes. Personal history absolutely plays a role in my work.

F-D: What influences outside the visual arts inspire and impact your approach to making work?

GR: I’m [heavily] influenced by science in general. To be honest, the visual arts affect my work, but I wouldn’t say that I’m thinking about other painters when I’m painting. I think a great deal about music. All of my work has movement as a critical element. Sometimes I think that my paintings are my way of making music.

F-D: Are you a musician?

GR: I am a musician, but I just play guitar by myself— I don’t really play with other people. I would say that music has the biggest impact and I would love to think that if a viewer has a strong reaction to music that they’d have a similar reaction to my work. I would love for it to bring up an emotion, or to cause them to stop and have to see for a moment. I feel like a sponge. I get influenced by just about everything. I read a lot and I’m writing down notes all of the time. You never know where it’s gonna come from: it comes from everywhere.

F-D: What are you reading right now?

GR: Right now I am reading this. . . kind of. . . science fiction-y series of books. They’re by David Lynn Golemen whom I just stumbled upon in the public library. They’re just really pulpy and weird and I love it. I’ve been crushing his books since April and I can’t seem to stop reading them. I’ll usually read a couple of pieces of fiction and then hop into a piece of non fiction. When I was reading The Doors of Perception I was really kind of into the after life, visual awareness, and perception. I have phases. This past summer I was all about the cosmos. I was reading up on the solar system and I’m embarrassed to say that I didn’t know a great deal about it. The ironic thing is that I wasn’t really aware that we were going to have a solar eclipse when I was going through that phase. Then when I found out I lost my mind a little bit. I try not to read too much of the news. But that’s awfully hard because I’ve become a bit of a political junky. I wasn’t, but it’s become unavoidable. I mean, I started this painting the day after the election. I was like, “Man, I’ve gotta make something and it’s gotta be big and pink”. Now it’s like an addiction.

F-D: What does having a physical space to make art in mean for your process, and how do you make your space work for you?

GR: Well, like I said, the space kind of dictates the work. I’ve worked in big spaces and I’ve worked in studios that were in spare bedrooms. When I was in that large space, I tried to make big work, but I couldn’t wrap my head around it in the same way. So, working on a wall that’s lofted right here allows me to visualize and be able to breathe and get some physical space in between myself and the work. And perhaps that’s why I’ve started moving toward this three dimensional style of work: maybe because I can’t go larger or taller I began to think that I had to come down here. Who knows, it makes sense now that I say it out loud. The space has a huge impact on the work that you make.

F-D: Do you see your work as relating to any current movement or direction in visual art or culture? Which other artists might your work be in conversation with?

GR: I don’t know how to answer that. When someone asks a question like, “where are you in history”. . . that’s for historians to decide. I think that’s a fine line, to think about where you fall in art history. I think you should just work intuitively and make work that comes to you naturally. In terms of conversations. . . Sure, I’d love to be talked about alongside [Haruki] Murakami. Sure! I love him, let’s talk about him. Jay DeFeo . . The Rose. . . I mean, when she was working on that, I . . . I mean, I just really relate to that. I relate to just pouring endless time, energy, and materials into a work. When I first saw that piece I responded to it on such a personal level. I think about sculpture a lot when I’m painting because I’m putting so many damn layers on there. So, yea. . . I’d love to be in that conversation. Color Field painters. . . sure. . . I’d love that. But to be honest I don’t really think about them so much while I’m making work. Making work for me is a very meditative experience. It’s sort of out of body, I mean, my heart rate even goes down. I don’t want to think about myself. It’s very intentional.

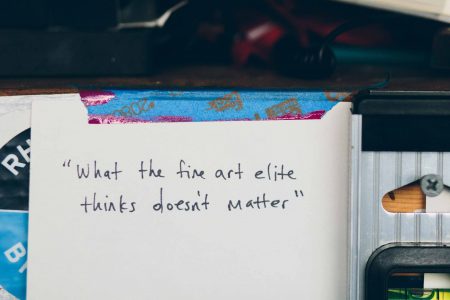

F-D: Do you have a motto or creed that as an artist you live by?

GR: Absolutely. It’s a Chuck Close quote. “Inspiration is for amateurs, the rest of us just get to work”. I just love “Inspiration is for amateurs”. Don’t wait around. Always be working. Always be working. It’s down deep and when your working it surfaces.

F-D: When asked; what do you tell people you do for a living?

GR: I tell them that I teach the visual arts. I’ve always had a hard time telling people that I was an artist. I have a weird relationship with that word because it means so many things now, it has been so watered down. I am an artist, but I don’t want to claim that until I am making a living doing just that. That’s my own personal obstacle that I’ve gotta get over.

F-D: Do you think that that is a bit of outsider syndrome kicking in?

GR: No, teaching is an influential part of my process and I take a lot of pride in it. I like to tell people that I’m a teacher, it’s not just a way to make money.It’s funny, I became a teacher because the schedule allowed me the time to make work. I’ve been teaching for a while, and those two parts of my life now have this symbiotic relationship. When you work with kids you get to be around all of their natural energy that just comes from youth and that feeds into my work. It’s just a good thing.

F-D: What risks have you taken in your work, or for your work?

GR: Well, when I first started working I gravitated towards color schemes that were more comfortable. I wanted to make work that was easier to place residentially. I wanted to move work. I was under the misconception that if I made work to sell I could afford to make the work that I wanted to make. Then I got to a point where I wanted to use the colors that feel right to me even if it melts your eyeballs. I’ve just kind of gone with the flow and tried to have faith in myself. Sometimes that’s a risk— to believe in your instinct when it may be counter to what others are doing or saying.

F-D: Words of wisdom?

GR: Trust the process, because it’s authentic and it’s you. You’re gonna get to where you need to be if you trust the process. Wherever that may be.

F-D: Is there something you are currently working on, or are excited about starting that you can tell us about?

GR: These guys that I have right here (points to two in-progress works).

F-D: Would they be shown together?

GR: Yes, with a few more that would live on the wall, a few on the ceiling, and this one. They’re like little black holes that appear to lead to other dimensions where you least expect it. I’m very excited about it, but it’ll probably take me a couple of years for me to complete.

F-D: Are you involved in any upcoming shows or events? Where and when?

GR: I’m currently working on a couple of commissions– one public and one private. Other than that, just working on new paintings.

–Megan Bickel