Stewart Goldman has been making art longer than many viewers – although not this writer – have been alive, a circumstance that does not seem to hamper either his relevance or appeal. By his mid- 20s, when the 20th century itself was in its sixties and seventies, Goldman’s work began appearing publicly with considerable regularity. He’s shown in many group exhibitions and has had more than twenty solo exhibition since 1961 in Cincinnati, Chicago, Springfield, (Pa.) and other locations in this country as well as being included in exhibitions abroad.

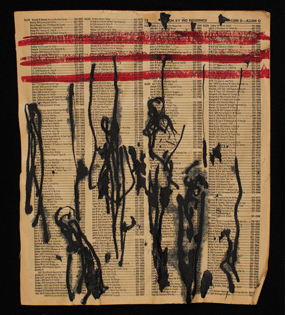

Next up will be a solo show, “The Hanging Figures,” at Skirball Museum, Hebrew Union College in Clifton, opening April 11 to run through June 2. The images, he says, are his “response to the actions of the German Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front in World War II.” In the late 1990s this set of works were part of an exhibition that traveled through a number of cities in Germany. Goldman has a long association with the Skirball Museum and Hebrew College. His work, so often strongly influenced by thoughts of the Holocaust, is a natural extension of the institutions’ interests and purposes. American-born himself, the artist is only a generation or so away from Europe. A grandmother’s birthplace, for instance, was “outside of Kiev, in the Ukraine.”

Goldman’s work moves easily between abstraction and representation but in my notes is a reminder that says “What’s not there is as vital as what is.” This is particularly true in a series of tape drawings, in which the removal of the tape leaves the telling space. Memory and loss are recurrent themes, strongly reflecting Goldman’s Jewish heritage.

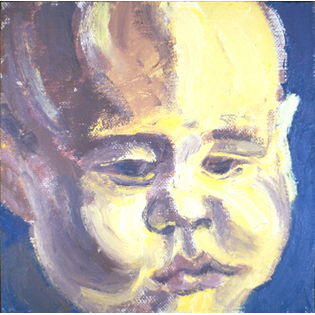

Cherubs make a perhaps surprising appearance in some of these thoughtful exercises of memory and regret. They are there in homage to children lost, damaged, destroyed in the continuing eruption of modern European wars. “People respond strongly,” Goldman said. “The mortality rate the paintings reflect is high. The Holocaust could happen anywhere.”

Goldman is an inventive artist, continually experimenting with unexpected combinations and contrasts. He makes photographs, on aluminum and plexiglass, that relate closely to the abstraction of his paintings. People are not present in his works in general. “I needed to make abstraction my own,” he told me.

A significant exhibition of his work appeared at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 2009: “Presence through Absence.” A reviewer at the time noted the works moved from representational “into the increasingly less certain terrain of abstract painting, not artistic schizophrenia.”

A visit to Goldman’s web site indicates that abstraction is strong and certainly his defining area. In the section “White Paintings and Precursors” (2008-2015) color seems there to define the white space rather than the other way around. “My interest is always in white,” he says.

Right now he’s working with watercolors after a long lapse in that genre. He spoke of his work as evolving – “I never felt impelled to stay in any one place.” Goldman uses his art, it seems, to help himself understand and interpret what is happening in the world. “Climate is disintegrating around us, significant things are happening,” he told me, and added ” but also the work is an expression, of my history.”

Goldman came to Cincinnati to teach at the Art Academy in 1968 and retired in 2001 but is “still in touch with some students. I have more time now, but I did enjoy teaching.” His own educational background is as a graduate of the Philadelphia College of Art with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting. He talks easily, is responsive to questions, but somewhere in our discussion his cell phone rang. He told the caller he would call back. “Grandchild,” he said in answer to my unasked question. Although people are not physically portrayed in this artist’s work they are the heart and soul of it and also, if a grandchild calls to chat, must have vital places in his life.

His studio, like many artists, is in the industrial area along Spring Grove Avenue. “Six minutes,” he said, from his home in Clifton. He has, in fact, two studio spaces, having outgrown the original but still using it. Both, now, also shelter large, very healthy looking, outdoor potted plants – “here for the winter” – that will return to the Clifton house when summer comes. The children are grown and gone (daughter is a lawyer in Brooklyn, son an educator in Germany) but he and his wife Kristi Nelson, Provost and Senior Vice President at the University of Cincinnati, still live in that convenient location for the work of each.

They are active members of their community. Stewart himself has been a board member for the Cincinnati Art Museum and is now on the advisory committee for the Weston Art Gallery and has served in various capacities for other organizations including the Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education, the Ohio Arts Council and Gamble-Nippert YMCA. In 1988 he received the Cincinnati Post-Corbett Award as an Outstanding Individual Artist.

Painting never palls for Goldman. He spoke of its being “intriguing and challenging” and of “color evolving” and that since November he’s been “inventing ink lines” in four colors, applied one at a time.

With artists, one always wants to know – what’s next? With Goldman, there’s often something new on the horizon.