The Waite Smith-Barrett Home in Indian Hill represents, by default, the oldest house in Cincinnati, having originally been built

in 1778 in Watertown, Connecticut before being moved here

in 1953.

Photo by Alice Weston

As a city that is 231 years old, Cincinnati has enjoyed numerous buildings of various styles, some of which fortunately still have survived. An exhibition at the Downtown Cincinnati Public Library entitled “Cincinnati Historic Architecture: An Overview of 150 Years of Architectural Styles” will be on-view until April 28 and is worth visiting to appreciate our history as well as our present.

By default, the earliest building in Hamilton County is the Waite Smith-Barrett Home of Indian Hill built in 1778: it is noted conditionally because in 1953, the Richard W. Barrett family had it moved board-by-board from Watertown, Connecticut to Cincinnati. The home’s classic lines, double-sloped gambrel roof, Georgian symmetrical window placement, and clapboard exterior façade with wood shake shingles all meld sympathetically in its more recent local wooded surroundings. Its interior contains fine original architectural features including a multi-colored trompe l’oeil marbleized paneled fireplace wall in the back room, now used as the family room. Of particular note, these photos and some of the descriptive historical account of this home and a few others came from architectural historian and author Walter E. Langsam and photographer Alice Weston in their 1997 book entitled Great Houses of the Queen City.

This panelled fireplace wall in the back room

of the Waite Smith-Barrett Home has

a rare and splendid original marbleized surface treatment.

Photo by Alice Weston

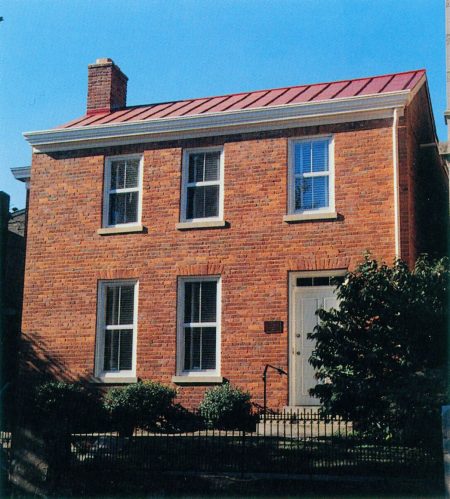

Legitimately, the William Betts House, which was built in 1804 and owned by the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in Ohio, is the oldest building on its original site in Cincinnati and the oldest brick home in Ohio, having been constructed just 1 year after the founding of our state. Now a museum of building technology, it is located in the West End neighborhood near Music Hall (1878) and just blocks away from the new behemoth FC Cincinnati Soccer Stadium, the latter being totally out of scale with its residential surroundings. The simple Federal Style Betts House offers a glimpse into the earliest remaining vestiges of our city, as built by a brick maker and farmer.

The William Betts House, located at 416 Clark Street

in the Betts-Longworth Historic District west of Music Hall, is the oldest building in Cincinnati on its original site, dating to 1804.

Photo by Alice Weston

The exhibition is loosely organized by building types, including residences, churches, hotels, offices, railroad stations, theaters, museums, public buildings, jail, and others. Commendably, it gives not only a brief description of the featured structures, but also identifies the original owners and architects, often overlooked by history. Certainly, an exception to this is Samuel Hannaford, a name that is well-recognized locally for his fine, successful architectural career (City Hall and Music Hall are two of his best known surviving and revered projects which are in this show). However, James W. McLaughlin was his major competitor in the last half of the 19th-century and is still not as well-known by comparison, but definitely his equal in design, if not superior. Photos of McLaughlin’s projects include the original Art Museum (1886) and Art Academy (1887), as well as a home, later converted to offices for the Cincinnati Gas Co., formerly located at the corner of Clifton and Ludlow Avenues: this rarely seen image was of a short-lived structure, since it was replaced in the early 20th-century by the Clifton Fire Station. Not to be missed is a large, horizontal display case that contains original section and floor plan drawings in ink and colored pencil of McLaughlin’s Main Public Library Building (1870). The skylit, multi-floored atrium (very advanced for its day) remained the library’s home until 1955, when the move was made to its present location on Garfield Place, designed by Woodie Garber.

Of historical significance is a photo of the David Gamble Residence designed by Hannaford and formerly situated in Avondale near the present-day Fleischmann Gardens. Built in ca.1886, this exterior image is one of the few which has survived of this Late Victorian turreted mansion with Flemish gables and wrap-around porch. By 1908, the Gambles had moved to Pasadena, California where they hired the firm of Greene & Greene to design the famous, iconic Arts & Crafts Style home with its open plan, low slung profile, wide overhanging eaves, and Asian influences—the antithesis of Hannaford’s earlier home for the Gambles in Cincinnati.

Besides recognizing familiar landmarks which we pass daily, it is poignant also to reflect upon previous structures that no longer exist, such as these demolished Hannaford and McLaughlin buildings. Another example of this is a famous corner: Fifth and Vine Streets as seen from Fountain Square, appearing totally different today. Several photos from slightly shifted positions include a view of the previous Carew Building at that corner, where the 49-story Carew Tower stands in its place. Not identified in the photo to its left are the Hotel Emery and the earlier Arcade, also later replaced by the Carew Tower/Netherland Plaza Hotel Complex (1929-1931). With another repositioning of the camera, the image of the Albee Theater (1927) is captured, near that same corner on the south side of Fifth Street between Vine and Walnut. This theater with its elegant white Carrara marble Palladian-arched façade was much fought over in the 1970’s, when it was threatened with demolition to make way for Fountain Square South. Unfortunately, the theater was destroyed, but the exterior was spared and relocated to the south side of the Duke Energy Convention Center along Fifth Street on axis with Plum Street. This represents an early preservation victory of sorts for our city, which until that point had suffered mostly losses.

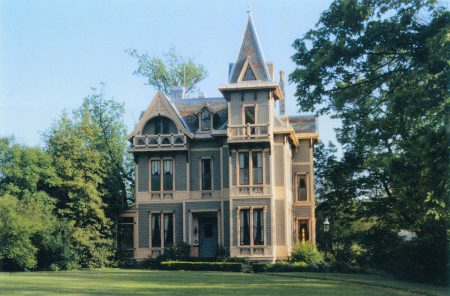

The George N. Stone House (ca. 1880) in Hyde Park was designed by architect Samuel Hannaford in the vertical Stick Style of Victorian Architecture, with its “balloon frame” structural system emphasized by the “painted lady” color scheme.

Photo by Alice Weston

It is noteworthy that not all of these images represent “Lost Cincinnati”, and credit must be given to Cincinnati Preservation Association and individuals with foresight who possessed a sense of heritage in having saved so many of our buildings. This appreciation of our history defines us as Cincinnatians, and allows residents and visitors to marvel at our sites today and

for future generations to enjoy tomorrow.

–Stewart S. Maxwell

April 1st, 2019at 4:46 pm(#)

A really well done article and incite into the history of Cincinnati architecture. Growing up in the area I remember so many more beautiful architecture that has been lost and/or tossed aside for the “new image of Cincinnati.” Those beautiful theaters and architecture that has been lost forever. Hopefully the new and younger generations will discover the beauty in what was instead of the serial industrial boxes we call home today.