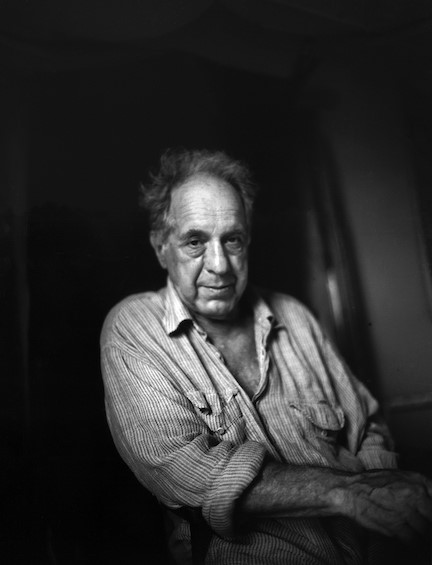

In the autumn of 2019, two giants of American photographic arts died, a mere seven days apart from each other. They were close friends and neighbors in the New York of the ‘50s, at one time even working together on the same project (a film). Both were Jewish, and deeply humanistic, and both had children who died before they did. One is probably the most important photographer of the second half of the 20th century and a legend in his own time. The other is less well known as a photographer, but a legend too, as his accumulative accomplishments in so many fields together perhaps surpass his old friend’s. I remain in awe of both.

Robert Frank was the older of the two, born in Switzerland in 1924. His father was German but became stateless after losing his citizenship as a Jew. Switzerland was neutral and a refuge, but Nazism and Fascism were all around, creating what Frank called ‘‘a sad household.’’ Zurich radio was full of Hitler. ‘‘That voice cursing the Jews,’’ he says. ‘‘You couldn’t turn off the voice.” Frank left Switzerland, emigrating to the US in 1947, settling in New York City.

But he remained restless, returning to Switzerland in 1949, then traveling about Europe and South America, his Leica camera essentially his passport. From time to time he produced hand-made books of his photographs, the first of these in Switzerland then another of his work in Peru.

1950 was a pivotal year for Frank. He met Edward Steichen, the head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, who included his work in the group exhibition 51 American Photographers, and he married the artist Mary Lockspier (Frank) with whom he would have two children, Andrea and Pablo.

For a time he moved his new family to Paris but returned to New York in 1953, meeting and connecting with photographers like Saul Leiter and Diane Arbus and taking free-lance assignments from various magazines (although repeatedly spurned by the editors at Life Magazine, whose publisher Henry Luce preferred more narratively obvious work). Even the storied photography collective Magnum, then presided over by photographer Robert Capa, passed on Frank; “Capa said my pictures were too horizontal, and magazines were vertical,” Frank explained dismissively.

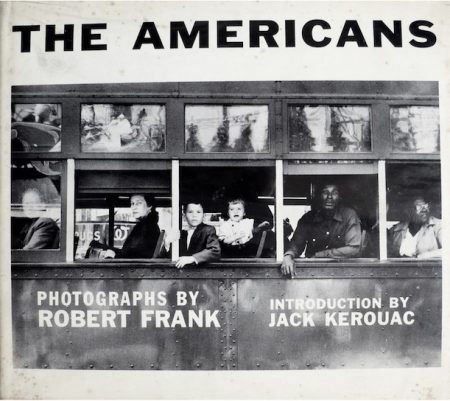

In 1955 Steichen included seven of Frank’s photographs taken in several countries in the ubiquitous exhibition and catalogue The Family of Man. Steichen also helped Frank obtain a Guggenheim Fellowship (along with Walker Evans, Alexey Brodovitch and several others) which set him free to travel the entire country photographing as he wanted. 83 three of the more than 27,000 photographs he made on his trips over the next two years were selected and sequenced by him to become his masterwork and seminal book, The Americans.

The American broke all the rules of photography and photojournalism, of photography books and social norms. It was somewhat inspired by three other works: Swiss Jakob Tuggener’s 1943 filmic book Fabrik, Bill Brandt’s The English at Home (1936) surveying societal strata, and Walker Evans’ American Photographs (1938). Frank’s take on America was darker than Evans’, and his view broader than Brandt’s. The grainy pictures contained movement and blur, the camera sometimes tilted, subjects were off-center. There were no captions; you had to “read” the images, then travel through their sequencing to discern meaning.

“View from hotel window, Butte, Montana”,1956, copyright © The Andrea Frank Foundation, from The Americans; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

At first American publishers wouldn’t touch it, as it’s picture of America was far from rosy; so it was first published in Paris by Robert Delpire in 1958 as Les Americans, with an introduction by Evans (but also texts by Simone de Beauvoir, Erskine Caldwell, William Faulkner, Henry Miller and John Steinbeck interspersed with Frank’s photographs). In 1959 Grove Press published it in the US more as Frank had intended it, without texts, save a new introduction by the Beat writer, Jack Kerouac, whose On the Road was published in 1957 and impressed Frank with “the speed of it, taking you back and forth across the country, his descriptions of the landscape in the morning, the little towns, which he describes with such exquisite beauty — the love for America.’’ Kerouac’s intro in turn praised Frank, writing “With one hand he sucked a sad poem of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.” “To Robert Frank,” he ended his text, “you got eyes.”

“Candy store”, New York City, 1955, copyright © The Andrea Frank Foundation, from The Americans; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Sales of The Americans, slow at first, increased as Kerouac’s involvement proposed it to a younger audience and the work began influencing other photographers. At the time photography was what Walker Evans termed “a disdained medium” with very few American art museums exhibiting or collecting it (Frank frequently complained that the Museum of Modern Art refused to sell The Americans in its shop). In 1961 Frank received his first solo exhibition, at the Art Institute of Chicago – by which time he’d already given up photography to make films. By the time I fully appreciated the book as a student in San Francisco in the late ’60s, it was iconic, virtually revered amongst the photography students. It remains to this day one of the most influential books of photography ever published. Peter Schjeldahl, longtime art critic at The New Yorker, called it ‘‘one of the basic American masterpieces of any medium.’’

“Car accident, US 66, between Winslow and Flagstaff, Arizona”, 1955, copyright © The Andrea Frank Foundation, from The Americans; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Frank’s abandoning photography just as The Americans received its US publication shocked the photo community. After publishing one more, small body of photographs made from the windows of often moving New York City busses in 1958, Frank turned to creating films which also broke most of the accepted rules of filmmaking. The first of these, in 1959, was the freewheeling Beat masterpiece Pull My Daisy, with performances by Alan Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and other Beats, with Jack Kerouac’s narration. Frank continued making personal films through the 2000s. Younger directors would later revere Frank as the godfather of independent film.

“From the Bus”, 1958, copyright © The Andrea Frank Foundation; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Probably his best known (most notorious) film is the 1972 Rolling Stones documentary Cocksucker Blues. A contentious fight with the Stones resulted in court orders restricting its presentation in the US to just five showings a year and only in the presence of the filmmaker (I don’t know where this stands now that he has died). In ’72 he also published a new volume of mostly old photographs, the autobiographical The Lines of My Hand, with photographer Ralph Gibson’s Lustrum Press.

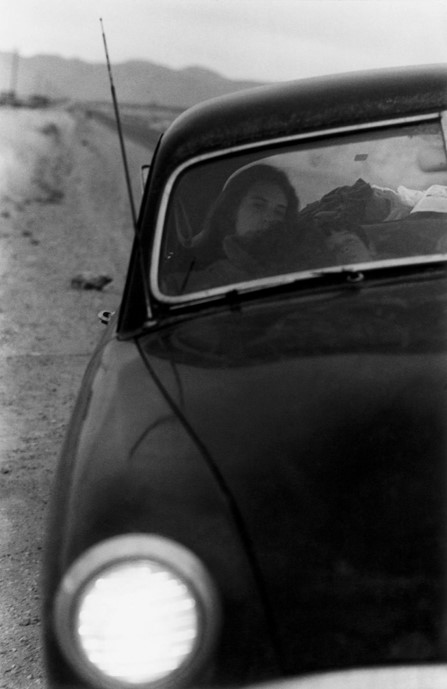

I met Robert Frank only once, when Gibson brought him to the San Francisco Art Institute in 1971 or ’72. There we printed out and hung enlarged versions of his contact sheets for The Americans (a revelation) and he looked at some of our portfolios. He was silent looking through my photographs, so much so that I thought he found nothing of interest. Then suddenly he pulled one out and held it over his head, demanding everyone come look at it. So, one! That emboldened me to speak to him, photographer to photographer, and I asked him about the last picture in The Americans, looking back at his wife Mary and son Pablo in the passenger side of his second-hand Ford, “Luce” (the only connection he ever had with Mr. Henry Luce, he’d say).

“U.S. 90, En Route to Del Rio, Texas”, 1955, copyright © The Andrea Frank Foundation, from The Americans; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

But I’d overstepped unseen boundaries (I hadn’t realized the marriage had recently dissolved or that Frank likely felt responsible). I don’t remember exactly what I asked or his reply, but I remember how it felt: like a knife inserted into my guts, twisted, then jerked upward. It literally took my breath away and ended the discussion. You could see something like that on his contact sheets too. Usually just two or three jabs before landing the knockout, almost always the last shot, before moving on. He knew when he’d got what he was looking for and that was it. It was that self-knowledge that enabled him to leave being a street photographer; he’d done what he set out to do and did not intend to repeat himself.

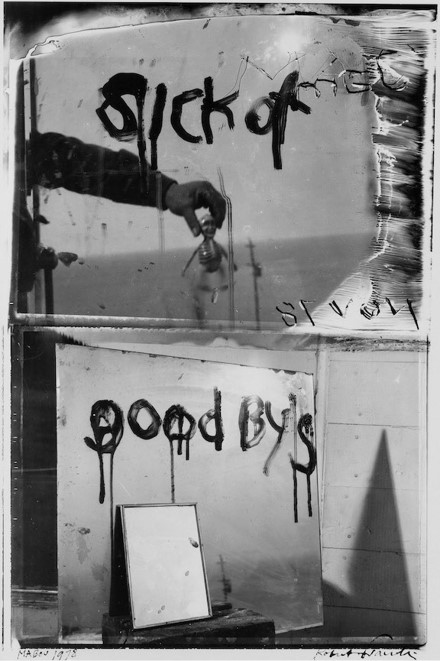

“Sick of Goodby’s”, Mabou, 1978, © The Andrea Frank Foundation; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

As the years passed Frank made the occasional singular photograph, often in Mabou, Nova Scotia, where he’d settled, having remarried the sculptor June Leaf. This unexpected return to making photographs produced unexpected images: personal, self-reflective, messy and mostly sad; sometimes written in or on, often as elements in collages, and often achingly personal. He lost both his children, Andrea in a plane crash in 1974 and Pablo from suicide in 1994, after struggling with mental illness. Andrea’s death particularly turned him more inward and solitary.

Over the past decade, working with the German publisher Gerhard Steidl, Frank became something of an industry, mining his entire photographic output, producing new books almost annually. His prints sell for small fortunes (although he continued to live simply, putting the money to work in a charitable foundation named for Andrea). His influence seems undiminished.

Robert Frank died on September 9, 2019, at his home in Nova Scotia.

Here are some quotes of Frank’s I like:

Black and white are the colors of photography. To me they symbolize the alternatives of hope and despair…

I’m always looking outside trying to look inside, trying to tell something that’s true.

The eye should learn to listen before it looks.

When people look at my photographs I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.

Little by little, you see what moves you. The pictures have to talk, not me.

William Messer is a photographer, curator and critic based in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has written for numerous publications in a dozen countries and curated/organized more than 100 exhibitions presented in nearly 40 countries. For the past decade he has curated photography exhibitions at Iris BookCafe and Gallery in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati. This October he was elected a Vice-President of l’Association International des Critiques d’Art (AICA) in Paris.