“I think probably every student in art school has these fantasies of ‘making it’ as an artist in the art world—the next Picasso, the next Diebenkorn; this is because you are still that ‘artistic’ child that believes you (and only you) are the only one that exists, that feels, that touches and that experiences life as an artist—and everyone around you is just a part of this ‘play’ that you are in, you know?”

~Cedric Michael Cox

It is not every day that I am able to watch an artist sell a painting (Golden Mist) right before my eyes, but that is exactly what happened to Cedric Michael Cox after his talk for “Planting the Seed,” a faculty exhibition at Kennedy Heights Arts Center, Saturday, September 12, 2014. Cedric’s natural demeanor is a large part of his success, both as a musical artist and as a visual artist. He is a people person. He enjoys human interaction. He immediately connects with his audience on a personal level, and his audience spurs him on. I was thrilled to see Cedric’s goals and “aspirations,” come to fruition that day: he created an instant and intimate bond with his viewers.

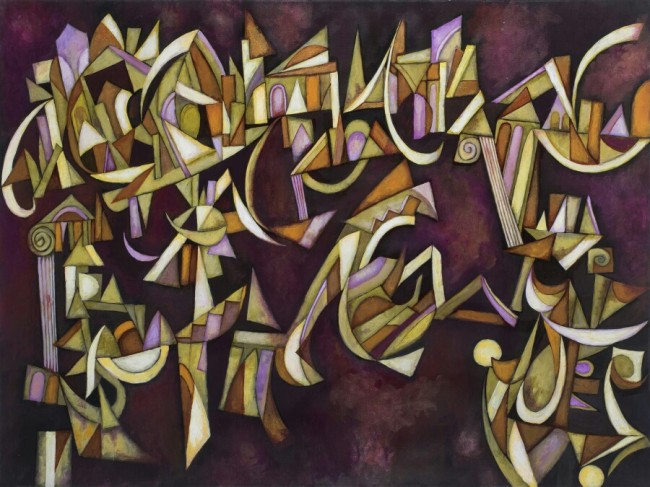

Cedric Michael Cox, an African American representational abstractionist, creates intricate and complex mixtures of futurism, surrealism, cubism and deconstructivism on canvas. There is a deep, almost impenetrable quality to his artwork. Cedric is much like his work, “Architectonic Lyricism,” and he is always pushing and pulling himself to achieve his goals or “aspirations”: he wants to entice, and then capture the viewer—into his “world”—his personal life. In return, he is able to view his work as both viewer and as artist at the same time. He is not afraid to bare his soul on canvas if that is what it takes to bring the viewer in and out and back and forth into his personal environment—and, obviously, as I witnessed that day at Kennedy Heights Arts Center—it works. “Architectonic” is the term Cedric uses to describe the atmospheric cityscapes he creates by producing “recognizable” organic, biomorphic forms. “Lyricism” describes the patterns and structures of his “speed metal” compositions; essentially, heavy metal rock.

I certainly cannot begin to explain the artistic process behind the work of Cedric Michael Cox. Only the artist himself can discuss his inimitable style in such an intelligent and effortless way:

“Even at an early age my artwork made a strong impression on my classmates and my teachers. I was able to connect with these people on a personal level—and these people were individuals that I didn’t usually interact with on a regular basis. I believe that these relationships created a certain level of confidence and respect for me and for the craft.

“Drawing made the largest impact on me, and everything just clicked when I began to draw random rock n’ roll images and the names of ‘speed metal’ bands on the covers of my textbooks. I liked the freedom of the ball point pen, of making a mistake, going from dark to light, and layering imagery. I wasn’t thinking about color, I was thinking about composition. There’s an attitude with heavy metal music: big, bold, and loud. It spoke for me: ‘I want to be seen, I want to be noticed, I want people to understand where I’m coming from.’ I used to perform in a band and I can still see myself on stage, playing intimately for my audience (the viewers). My music is my voice—my visual voice—and the songs that I write and compose are really written for visual experiences, not for rock star status. I’m thinking about these patterns and sequences—notes and riffs; the rhythm of this structured heavy metal—it is this rhythm becomes a drawing and then a painting. It’s just me and my guitar. The music is in my mind; I don’t let it guide my brush or my pencil. I just let it happen. Sometimes the music is in the background; sometimes it is just there.

“My songs are structured as to how I see my art: there is a lot of dark mystique to the kind of music that I play, in what I do. For me, however, I find my music light and uplifting. The music is just a tool to help, almost a metaphor for how I see life as patterns; life as coming back and forth, as ebbing like a tide, life as a crescendo, and then back again.

“I have many drawings to use for many of my newer works; it’s just a matter of blowing them up, making them bigger, and then carbon-copying them to the canvas. With the looser, more fluid work, I’ll start out with a random drawing, which is the core of the piece. I repeat certain forms. I will reverse and flip these forms so that they mirror each other. So, the drawings become the paintings. It’s ironic, because in my more fluid and abstract work, I am putting more into the drawing and the planning, because I am dealing with so much negative space. The work is so much about color and planning; however, I’m not trying to throw everything into the work: I want to make sure that what I do throw into my work is relevant.

“I have to be able to step out of myself for the viewer to understand me, and my work; essentially, this is what I am trying to convey to the viewer. My goal is to see my work from a distance, so that I can honestly and critically take a deep look at who I am inside—so that I can take a step back and ask myself, ‘what am I doing next?’

“The paintings themselves are not symbols of what I am thinking—they are symbols of my aspirations of being a better person. I think it’s up to the viewer to decide. I want the viewer to have fun. I like what I do, and I want my audience to enter into this world of rhythm, of movement, and of happiness. It’s not always going to be about movement, or about music; but, there is movement, there is rhythm within us, and I want my audience to be able to feel that movement.

“In 2008, I started progressing past the graphite drawings, trying to find a voice again with painting. I began to see things almost like a grid again—it was ‘moving’: a deconstructive break up of space spinning within the cityscape. Different levels—similar to burrows—above the cityscape began to take on different meanings: the cityscape and the organic forms started to mesh.

“I remember, however, finding my way in college. I finally found the medium that expressed who I really was inside: my upbringing, my joys, my passions. This medium was drawing. I was tired of color, describing the abstractions, distorting biomorphic nature and creating my own Cubist language. I began to ask myself, ‘what is my inner being? What is my inner spirit?’ I needed to ask myself, ‘what am I drawing? What am I making? What is this?’ The answer was through the use of graphite and pencil—raw and honest. I started becoming familiar with the work of Arshille Gorky and Cy Twombly in school, looking at looser, more gestural drawing. Since I’ve always had a very futuristic style in most of my work (optimistic and progressive), my professors suggested that I refer to Twombly to loosen up (there was not a lot of contrast to my work). I was working to the edge (similar to Paul Klee)—using the same level of execution, but I was showing a variation of this contrast. In 2012, I started to understand the reason why Twombly was recommended by my professors: I needed to guide the viewer through contrast within a composition— not color contrast, but form contrast. This was when I began creating more atmosphere(s) within my work—the musical, ‘Architectonic,’ organic forms.

“There’s one piece entitled, Golden Mist, at Kennedy Heights Arts Center. This work was just a spontaneous creation; actually, it was going to be a color study. With Golden Mist, I wanted the viewer to experience my hopes and my aspirations; to continue the power of the atmosphere against the power of the recognizable imagery. That’s what it is all about: I think both of these aspects cannot live without the other.

“Similarly, another piece, Totems in the Mist, at Northern Kentucky University, became a spontaneous, mysterious work using primarily green, purple, and mauve—a very misty, very tribal, very jungle-like atmosphere. I took the work to the next level by adding more recognizable imagery (pines and bushes); then I brought the work back down to a human level.

“I exhibited a very special piece, entitled, Figs Dancing in the Midnight Mist, at Northern Kentucky University. Kay Hurley inspired the background. Then, I just threw one of my crazy blue skeletons on top of the entire rendering. I broke up the space with this skeleton by layering on these tiny dancing entities. These entities completed the piece. Figs Dancing in the Midnight Mist has a quilt-like quality as well because it has a vertical style, similar to Paul Klee. ‘Architectonic Lyricism,’ or, the work exhibited at Northern Kentucky University, was a retrospective of the first 15 years of my career.

“There are people that walk up to me and ask: ‘What are you going to do next?’ And, as I just mentioned, this is basically the first 15 years of my art career, so sometimes, I feel like saying, ‘don’t worry about where my career moves!’ But, I think there will be stages in my career when I will concentrate on form rather than color. I think I may be ending this part of my career…maybe, who knows? I feel in limbo at this point. Still, the statement of my work reads: Graphite, Cityscape, Fluid. I simply have to keep evolving. And yes, I think other people make me accountable for what I do. I think that’s important. I do care about what people think, what people do and what people say regarding me and my career. At the same time, however, I have to take care of myself. I have to make sure that I take a step back before putting myself in difficult situations—too much in the public eye or saying ‘yes’ too often. I really need to make sure that I organize my life and my career in order to work and to move on.

“In 2011, I produced the Avondale mural for Artworks, which truly allowed me to step out of myself (the mural is still there on the Avondale Shopping Center wall). There is a certain sense of optimism in that painting (actually, it shows the color direction and fluidity of my current work). I think when I used to represent architecture—and architecture only—I focused on the rustic, the ancient, and the rural; I was trying to find the glory and the beauty in celebrated ruins. When I began working on the Avondale mural, I started thinking, ‘okay: vivid, bright, lift up.’ My work is still ‘Architectonic,’ but now it is more focused on light, happy, uplifting experiences. It’s about what I find pleasing within the world I see around me, and reconfiguring this world. I see some of these paintings as spontaneous combustions of energy: balls, or streams, or ribbons of energy that express my artistry and my personality. I want to pursue working with these bursts of energy.

“As a 2-dimensional artist, I am trying to make my window into the world real to the viewer. That’s what these works are all about: windows into the world I see, and how I am trying to ‘tune in’ viewers. The best inspiration for me, personally, is to have the ability to be honest with myself; I mean, if more work can be put in, more work needs to be put in. I have to be my best and my worst critic, and I have to be able to say to myself, ‘I can do better. I can do more. I can get my message across better. Just do this.’ I have to work it. I have to be humble and say, ‘you know, Cedric, this is really bad,’ [laughs] and move on. One is going to discover what one wants to do naturally.

“But, yeah, it’s cool. It’s a good thing. It’s a good thing.”’

After the lecture, Cedric said to me, “I don’t know how I did it, Liz,” almost sighing, “I guess I did something right.” I had to remind him that he had just sold Golden Mist that day. He had another patron inquire about his painting class at Kennedy Heights Arts Center. He had other patrons ask about his Website. “Cedric,” I answered, “you’re cool. And that’s definitely a good thing.”

“Planting the Seed: Kennedy Heights Arts Center Faculty Exhibition” will close September 27, 2014.

-Elizabeth Teslow