“Creativity is a lifelong process which requires courage, perseverance and hard work,” said Jane Alden Stevens.

Winner of the university-wide Dolly B. Cohen Award for Excellence in Teaching at the entire university in 1991, Stevens had an illustrious career as a teacher of photography at University of Cincinnati’s College of DAAP. Stevens was described in her nomination as having the quiet power to change lives.

A magna cum laude graduate of St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, she received a degree in 19th century European Studies. “I really didn’t know what I wanted to do,” said Stevens. Fascinated by art history during a junior year abroad in Germany, Stevens decided to earn a Master of Fine Arts in photography from Rochester Institute of Technology. She joined the faculty of UC and eventually became an assistant professor of photography, after researching the field. She freelanced for awhile: “I didn’t like covering political campaigns or weddings”, she said. So she looked into teaching, which became her career.

Stevens eventually joined the tenure track at UC and stayed for 31 years. During her career, she won Individual Artist grants from the Ohio Arts Council in 1990 and 2002. Solo exhibits of her work have been mounted at the ARC Gallery in Chicago, the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art in Ithaca, NY and the Pittsburgh Filmmakers Gallery. In addition, she has exhibited internationally, in Finland, Ukraine, Belgium, Germany and Brazil. By 2013, she retired as professor emerita of Fine Arts. Her work was most recently exhibited in a solo show at Phyllis Weston Gallery , in O’Bryonville, in 2012.

Her career included an exhibit entitled Tears of Stone: World War I Remembered, shown internationally, including at the Underground Photo Gallery in Iisalmi, Finland. The work turned into a book with text in English, German and French, and was published in 2004.

Exhibiting in Inner Mongolia, she displayed a work called Folk Culture and Nonmaterial Heritage in 2011. Seeking Perfection was an exhibit where photos were suspended from a sapling tree. She chose the unusual subject of how Japanese grew apples in a traditional and laborious way , based upon an article she read in The New York Times. Shadowing the Gene Pool was done with an antique panoramic camera. In this exhibit, she dealt with aging and explored the psychological evolution from child to adult. People in Environments literally were pictures of individuals in nature often shot from her cabin in the Adirondacks in Crown Point, New York. The Cincinnati Art Museum owns one of her pieces, Midsummer,from Shadowing the Gene Pool.

In addition to a busy teaching schedule, she put in 15-20 hours of art related work monthly preparing for shows. “I loved teaching; I loved creating,” said Stevens. “I never felt conflicted about doing both. I got so much from the students and had fantastic colleagues who encouraged me. It was easy to stick with it.”

“Reading and research underlie my artistic practice. Throughout my career I have studied aspects of psychology, sociology, art, religion, music, economics, agriculture, politics and geography to guide me when working on a project. This breadth of knowledge provides me with a multi-faceted perspective on the topic as I wrestle with it, allowing me to move forward to create metaphorical meanings that extend beyond the subject matter at hand,” Alden says in her mission statement.

“I find the work of Ruth Thorne-Thomsen and Shimon Attie to be deeply compelling, although my work looks nothing like theirs,” said Stevens. “ Both of them address history in multiple ways, both of them create pictures that evoke memory, both of them use technical tools in ways that are inventive and surprising. Their photographs force me to ask questions about the meaning of what I am seeing, and I like being challenged in that way. I never get tired of looking at their work.”

“Other artists who have greatly influenced me are composer Ludwig von Beethoven, whose passionate music is a force of nature; singer-songwriter Kate Bush, whose body of work is fascinatingly inventive and complex; and writer Alice Munro, whose short stories are so revealing of human nature,” added Stevens. “She can say more with fewer words than any other writer I know.”

“The ability of all these artists to both disturb and delight is something I admire greatly,” said Stevens.

“When I first entered graduate school in 1979, photography was a man’s world. There were dozens of male faculty at RIT, with only two female professors at that time. One of those female professors was Bea Nettles, who served as a mentor and role model for me.”

Nettles had two young children, an international profile as a photographic artist, and was willing to share with us her approaches to her career, according to Stevens. She came under a lot of fire from the male faculty who looked down on the content of her work as being irrelevant, as well as the technical tools she was using at the time, which were unconventional. Feminism entered the cultural lexicon while Stevens was a graduate student and then during her tenure as a teacher at UC.

Stevens said, “Nettles was one of the ground-breakers when it came to making one’s personal life and relationships the basis of legitimate photographic inquiry, and as it related to the use of alternative photographic processes for making one’s art, rather than conventional black and white or color tools. Bea’s approach to her art resonated with a lot of female students. I was deeply impressed by her ability to stay true to who she was as an artist despite the resistance she encountered. She served as an example of how to be professional, how to persevere in the face of adversity, and how to successfully stand up for oneself as a woman in a male-dominated field.”

“After I graduated and moved into teaching, I strove to do the same for my own students,” said Stevens. “Having seen another woman in the field succeed on her own terms empowered me, and I wanted my female students to feel the same when they left my classroom. I am a firm advocate of speaking up for oneself, learning to defend what you believe to be important, and being able to state and show one’s competencies to others. I strongly encouraged my female students to practice all of those things, which was particularly important when the ratio of males to females in the classroom was heavily male. (What’s interesting there is that the ratio of males to females in my photography classes shifted radically over the course of the past 31 years. When I started teaching, females were in the distinct minority. Today, it is the males who are in the minority, often by a large margin.)”

Talking about the difference between commercial photography and fine art photography, Stevens said that it used to be a question that came up quite often, but is heard less often nowadays. “I think that this is because there is far more overlap among the different photographic fields than there used to be. One can see the work of fine arts photographers being used for commercial and advertising purposes. It is quite common to find the work of photojournalists in art galleries and museums, as well as in magazines and newspapers. I have seen the work of biomedical and scientific photographers in art publications and exhibitions. There are wedding and other types of commercial photographs that are in museum collections.”

“And I prefer to focus on the result of the photographer’s efforts, regardless of what purpose they were intended for,” said Stevens.

“The field of photography is both similar and 100% different now than when I entered the field. The biggest changes have come, of course, in the technical arena,” said Alden. “Digital cameras record images differently than when film was used. The digital darkroom utilizes different equipment and requires a different workflow than the wet darkroom. The kind of photography that is ‘hot’ in galleries and museums has changed.”

“The ways in which photographs can be viewed has vastly expanded,” said Alden. “The worlds of moving imagery and still imagery are no longer as separate as they were. All of those changes required constant learning on my part in order to keep class content relevant, as well as constant rethinking of my own approach to the medium.”

“What has remained similar is the fact that cameras still use lenses and that lens vision (the way a lens records what is in front of it) determines the end result. People still tend to believe that what they see in a photograph is the truth, despite the fact that everyone nowadays has tools for image manipulation at their fingertips. People, more than ever, still want to record their world and express themselves through the medium of photography. And finally, photography still is a light-based medium, regardless of how one approaches it.”

“In summary, the technical advances in the field of photography meant that what I covered technically in my courses would change every year. But the aesthetic and ethical issues that I would address in each course remained pretty much the same over the course of time,” said Alden.

- Achiet-le-Petit German Military Cemetery, France

- Imperfect Apple, Summer, Aomori Prefecture

- It Was Just a Dream

- Muscle Girl

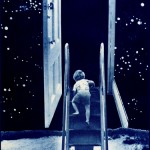

- The Open Door

To her, pictures create a metaphorical meaning, strange and unsettling. “They get people to ask questions and provoke thought,” she said. Her Birth and Death series examines the transition from birth to death in a linear progression.

Stevens does sketches or asks questions about historical events. “The hand of man is always there in my photographs,” she said. “I walk through the world and hope that the biggest impact of my work moved people or touched them internally or emotionally.”

Different pictures do different things, Stevens commented. Her photograph Muscle Girl empowered women at an important time in the evolution of feminism and gender studies.

“Students responded well to what I taught,” she said. “In many cases, students outperformed my expectations. I saw my role as a facilitator.” Stevens is still in touch with many of her students and happily so.

“There is no time to sit back and reflect when working. You discover your own path,” she said. Now retired, she spends all her time on photography. With free time available, she will look for new publications for her work. She lives in Clifton with her husband Gordon Barnhart and her twins Connor and Zoe, 18, seniors at Seven Hills School.

Stevens is happy to see FotoFocus, a biennial event, which brings attention to photography to town. She comments that the art scene in Cincinnati has room for different approaches to art. In a digital world, she says it is possible to make a living without being in a large city. Artists hate to do a lot of self-promotion, but it is necessary, according to Stevens.

“You need to stay in touch with the community, but it’s impossible to keep up with everything.”