As an artist ages, he or she becomes increasingly sensitive to the world and more uncertain of how to proceed. As the artist grows wiser, he or she must make the decision to continue groping for the elusive threads of memory and the constant uncertainty of personal experience. It is important for the work that the artist must stay uncomfortable. Cole Carothers has made this choice.

Round Trip, Carothers’s recent show in Covington, presented paintings of various sizes, shapes, and temperaments. Carothers has been in the game a long time now, but the work feels unexpected. Much contemporary painting deals in cold calculation, process and irony applied like a flashy veneer. Carothers’s current works feel vulnerable, divulging private glimpses. It is not that the subject matter is so personal: a window, muddy fields, a beach. The magic comes from how the paintings feel. Many hit you in the gut, although a few works feel sentimental and presented instead of created. Wonderfully, the work can fail because it reaches so high. From the potent fragility of Drive By Whiteout and Dunkel Landschaft to the fecund world of Swamp and the colorful work Cacti, Carothers is a risk taker. Stubbornly anachronistic, the power of his work relies on its transformative properties, not its content or materials.

Carothers’s paintings are expansive in their sense of touch. The paint is smashed, slapped, dragged, smeared, scraped, feathered, and redrawn. As viewers, we have all touched many different things in our lives. In their tactility, these paintings give us a sense of intimacy. We see the image but feel its physical presence. The paintings present a myriad of intuitive discoveries, each marked by a kinetic painterly event. Carothers was trained when the methods of Abstract Expressionism were law, and you can feel the digestion of action painting in the work shown here.

A more persuasive type of digestion is also at work: the digestion of memory and experience. Carothers often works from memory, and in his openness of heart to the essential constituents of an experience, he elevates his work from ambitious realist painting to serious art. Historical precedent exists for the kind of emotional memory painting that Carothers takes part in. The great painter Pierre Bonnard is present in spirit in Carothers’s work. Carothers is obviously not derivative of Bonnard in the look of his work, but the great gift of innocence and memory that Bonnard had is here. From the Brooklyn Rail in March 2009, Greg Lindquist wrote about Bonnard:

The transformation of subject into painting is fantastical—it is a translation of memory, recreating images with an otherworldly recollection that evades sentimentality yet remains deep with feeling.

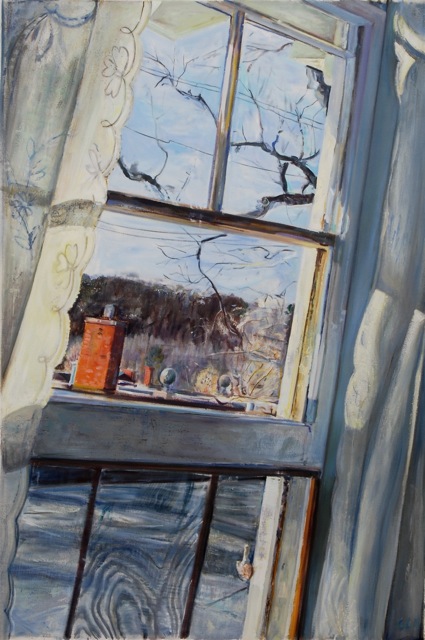

Carothers’s best work feels untethered in its historical context, wholly personal and urgent. A good example of this is in the large work from this year entitled Sideways Afternoon. This work is one of Carothers’s recent paintings that clearly depict local places. Here Carothers takes a subject he has been painting for his whole career, an open window. In many of Carothers’s earlier works, the view out of a typical Midwestern window might reveal a strange Italian landscape, and the disjunction between the two worlds lent the works a surreal charge. Sideways Afternoon also has a sense of the uncanny, but this time it is a specific feeling and experience. This painting feels personal. The window frame tilts at a strange diagonal referencing its photographic origins. This artistic choice involves us physically in the image. I found myself adjusting my body to try to gain perspective. The artist took the reference photo for the painting lying down in his bed at home. This explains the strange way the window frame leans simultaneously away and towards us. Peculiarities abound in this work, but none of them feels heavy handed. Take the screen at the bottom of the image. Strange dark concentric vibrations radiate upward in the middle panel. They seem to originate from the viewers vantage point, but they also pull inward like a whirlpool on the surface that points to seismic upheaval much deeper below. Conversely, the curtains are painted with a flat disdain, which reads grotesquely because of the blithe calligraphy of their linear decoration. Things seem much cheerier as we move out the window. Late day sun allows a saffron chimney to sound off against the gritty tones of the rest of the painting. In Sideways Afternoon, Carothers has allowed us in to his emotional world. It is a world of quirky humor, a profound connection to family and home, but also deep skepticism about the proportions of progress both personally and in the world at large.

Another very different work carries a similar level of sincerity. In the small visionary beach painting Taupe, a seemingly straightforward depiction of a seascape shimmers in and out of rationality. The sensation of shifting water and cold sky feel specific in their illusion, yet something is not right. The sky sits luminous but viscous and brown like chocolate milk that sustains three idyllic clouds. The beach is citron, and when it meets the titanium water, there is a supremely tender static of surf. This is a painting made from memory. Its source is a whole life distilled into a single image, a certain feeling. The source of this painting is not one beach, but a whiff of sunscreen that brings 30-year-old memories to the surface. The subject of this work is sentimental, but the viewer experiences it as personal nostalgia. A strange feeling of grief is present, although what has been lost is not clear. This candor comes naturally to Carothers, but its painterly language has taken hard work. With Round Trip, Carothers moves forward bravely in the face of uncertainty, and he does so with aplomb and grace.

— Emil Robinson