Earth, Air, and Water: Contemporary Landscape Painting

By Rick Bennett

Consider these two quotations about the place of landscape painting in the history of Western art:

“All Art is to some degree symbolic and recognition depends on certain long accepted formulae. The symbols by which early medieval art acknowledged the existence of natural objects bore unusually little relation to their actual appearance. But they satisfied the mediaeval mind. To some extent they were the outcome of mediaeval Christian philosophy. If our earthly life is no more than a brief and squalid interlude, then the surroundings in which it is lived need not absorb our attention. If ideas are Godlike and sensations debased, then our rendering of appearances must as far as possible be symbolic, and NATURE, which we perceive through the senses, becomes positively sinful. St. Anselm, writing at the beginning of the 12th century, maintained that things were harmful in proportion to the number of senses which they delighted, and therefore rated it as dangerous to sit in a garden where there are roses to satisfy the senses of sight and smell, and songs and stories to please the ears.”

–Kenneth Clark (from Landscape into Art)

“They paint in Flanders only to deceive the external eye, things that gladden you and of which you cannot speak ill. Their painting is of stuffs, brick and mortar, the grass of the fields, the shadows of trees, flowery meadows, bridges and rivers, which they call landscapes…And all this, though it may appear good to some eyes, is in truth done without reason, without symmetry or proportion, without care in selecting or rejecting… suitable for young women, monks, and nuns, or certain noble persons who have no ear for true harmony.” –Michelangelo

In light of these attitudes, it’s not surprising that in contrast with the East, landscape painting in the West developed quite late and has never enjoyed the official prestige afforded to figure painting or abstract art. On the other hand from the time it arose as an independent subject landscape has been and continues to be the most popular and marketable genre of painting. In a review of the recent group exhibition “Lots of Landscapes” at Allyn Gallup Contemporary Art, Kevin Costello writes: “Regardless of time, circumstance and style, landscape artists essentially respond to the majestic complexity of nature. As a mode of visual expression, contemporary landscape painting has shaped our understanding of our environment, and in recent times, made us conscious of the fragility of the biospheres contained within.”

Through the Modern and Postmodern periods landscape painters have been generally ignored by critics and curators but have continued to produce images. Contemporary landscape painters employ a wide range of styles but have in common some kind of reaction to Modernist formal experimentation, and even the most traditional of these artists work within a new historical context: the consciousness of environmental peril.

Influenced by the late work of Monet and Modernist abstraction, a number of today’s landscape painters have isolated and focused on specific elements, and this series will consist of three parts: 1. skyscapes, 2. waterscapes, and 3. paintings with traditional landscape viewpoints.

1. Looking Up: Jane Wilson, Tula Telfair, and P.A. Nesbit

The first of the skyscape painters this non-comprehensive survey will focus on is Jane Wilson. Wilson grew up in Iowa surrounded by big open skies. After receiving a traditional art education, she gravitated toward Abstract Expressionism as she began her career in New York in the early 1950s. After experimenting with abstract art, Wilson’s interest in landscape and light eventually won out over prevailing taste: “In 1956 and 7, I found myself in one of those lucid moments that occurs every twenty years and I realized I wasn’t a second generation Abstract Expressionist. I looked at the ingredients of what I was painting and felt an uncontrollable allegiance to subject matter, and to landscape in particular…The landscape was enormously meaningful to me,” she has said. “I used to roam around a lot by myself as a child, and when I think of a landscape, I think of the great weight of the sky and how it rests on the earth. And I remember the light. Light is specific to certain places, and what sort of light and landscape formation you grow up with is immensely influential to what you do later on.”

From the 1950s on, Wilson has been associated with a widely imitated square compositional format that features a thin strip of land at the bottom of the canvas while the main focus is on the sky–or on color and paint itself—as her spontaneous brushwork borders on gestural abstraction. In 1961, Wilson described her painting process in Art in America magazine:

“My paintings are done mostly from memory. After making simple indications of mass and movement, I start painting from the top down in thin color washes, working into it with paint a little thicker. While painting landscape, my feeling is that the detail and the mass are built on varieties of paint application, but when a painting is finished, these details have somehow become recognizable things. It is always a surprise to me how specific my paintings are. What I remember as color and paint put in a particular area of the painting because they were needed has somehow become identifiable landscape elements.”

Colorado Blue, Jane Wilson

Throughout a long and successful career, her compositional approach has remained consistent while the range of colors, marks, and suggested atmospheric conditions are marked by a rich variety. She has been referred to as an expressionist landscapist, and associated with the American Romantic tradition of landscape painters as well as with the Abstract Expressionists, and in fact Wilson’s paintings combine these categories simultaneously. While critics have found different labels for her work, they have been consistent in praising the power and beauty of Wilson’s paintings. Of her early work, Stuart Preston wrote: “[Jane Wilson] is a hedonist in paint, employing a plethora of strokes and bright colors…” Dore Ashton wrote: “[She] is a painter enchanted by the majesty of light. Her landscapes and even her figure studies are articulated in terms of the moods of the sun. Basically a frank expressionist, Miss Wilson brushes her landscapes energetically in strong color.”

In 1984, New York Times critic Michael Brenson comments on the power of Wilson’s paintings: “The human world seems to be holding its breath through different stages of a continuing, sometimes heated debate among earth, water and sky. … In these landscapes… the intelligence and will of the artist are so thoroughly interiorized in the pictorial struggle that the paintings are experienced by the visitor well before and long after they are really seen.”

Jane Wilson’s first solo exhibition was in 1953 as a charter member of the Hansa Gallery, one of New York’s first co-operative galleries. Wilson went on to have some fifty solo shows throughout the country, thirty of them in New York City. Her most recent solo museum exhibitions were presented at the Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York in 2001 and The McKinney Avenue Contemporary, Dallas, Texas, in 2003 and DC Moore Gallery in 2011. In 1985, Paul Gardner wrote of Wilson’s career: “In her own restrained way, without any pomp or puff, Wilson represents what the art world is about: staying power, whatever the trend of the moment, and a consistently developing body of work that results in a steadily increasing reputation.”

Tula Telfair, another contemporary painter, shares Wilson’s basic compositional approach but with strikingly different results. While Wilson’s work bears a connection to gestural abstraction and minimalism, Telfair style constitutes a conscious break with Modernism. Painted with smooth gradations of naturalistic color and minute details done with a single-hair brush, Telfair’s technique owes more to the American Hudson River School and the Northern Baroque landscape traditions than to any recent styles.

While Telfair’s paintings are highly detailed and illusionistic, she explains in her artist’s statement that they don’t depict actual places: “I make large oil paintings that combine images of epic landscape and dramatic weather with minimal elements of pure color. All the images are invented, and come purely from memory, not from observing a site, or utilizing photographic aids. Although many of the required elements of the sublime are present, placing the work within the Romantic landscape tradition, I employ devices that remind the viewer that these are simply paintings; two-dimensional surfaces covered with paint. Typically, several edges of the single-image paintings will be bordered with different colored stripes, while the multi-image works may include wider panels of pure color that separate the landscape images themselves. The colors used come directly from the image they surround. These lines and panels appear to shift their color as they come in direct contact with the landscape, and can make one edge of the canvas appear to be closer to the viewer than another. Even though the images may appear familiar, using titles like, Debating the Precise Nature of Space or The Power of Interacting Volumes, distances them from association with any particular place, affording the viewer the opportunity to recall a personal experience. While maintaining an awareness of the material object, the depicted epic moments in nature, generally facilitate an emotional response. I am interested in the subjectivity of perception and the power of memory, using illusion to trigger recollections of things past.”

In this sense Telfair’s paintings are commentary on the genre itself, but this is true of all successful painting and the references to constructionism seem targeted to those who feel that painting needs such justification. More open-minded viewers and critics are free to enjoy the color, patterns, and skillful evocations of light and space that the artist certainly revels in. Robert Fishko, Director of the Forum Gallery which represents Telfair writes: “Telfair combines stillness with motion, solitude with universality and definition with suggestion in her bold and generous paintings. Objects of undeniable beauty, they are filled with contradiction, clarity and curiosity. They are a brilliant extension of the progression of landscape painting from the Renaissance through the travelogues of the nineteenth century and the realism that followed.”

Like Jane Wilson, Telfair’s imaginary landscapes exclude roads, signs, telephone wires, evidence of agriculture, or any sign of human presence. Neither Wilson nor Telfair comment specifically on environmental issues, but both artists live and work on the congested East coast, and the continued references to vast skies and open spaces suggests a Romantic reverence for unspoiled nature. But while Romantics saw nature as a refuge from societal and spiritual corruption, Wilson and Telfair seem to use landscape painting as symbolic refuge from the corruption of the land itself. The nineteenth-century Romantics dramatized light and sky to connect them in more-or-less obvious ways to divine power. Wilson’s overt marks and Telfair’s highly resolved images both focus on the inherent material drama of the land and sky. Viewing a painting like Telfair’s Reduction Occurs in Less Obvious Ways, one wonders if such a view or such a place still exists anywhere on the earth. The traditional association of primeval, pristine land with spiritual renewal has given way to a revival of even more ancient associations of land with the promise of material sustenance and fertility. Telfair’s painting brings to mind the description of New York from the close of Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby: “…gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for the Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world.”

The contemporary painter who may be most closely associated the American Romantics is P.A. Nisbet. He works from on-site sketches and has traveled and painted the Antarctic, the Sonoran Desert, the Grand Canyon, and most of the western US. At one time Nisbet served as a line officer at sea with a ten month tour of duty in Vietnam. During that time he was appointed by the Secretary of the Navy to serve as Director of Art Services for the Navy’s Office of Information. (Who knew there was such a position?) Later he was commissioned to paint the space shuttle for the NASA art program.

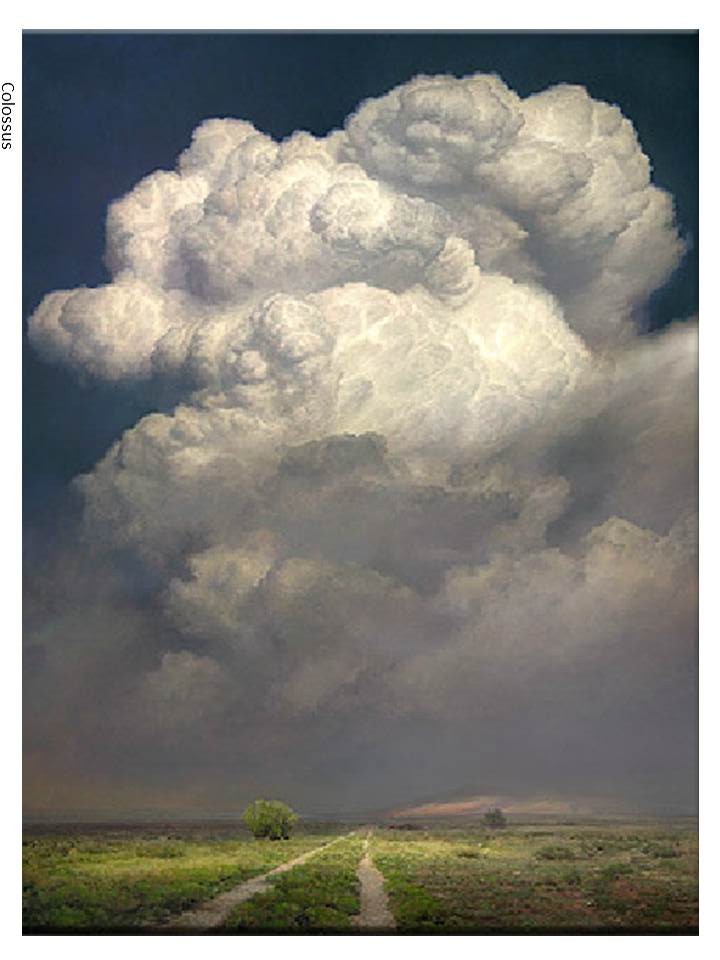

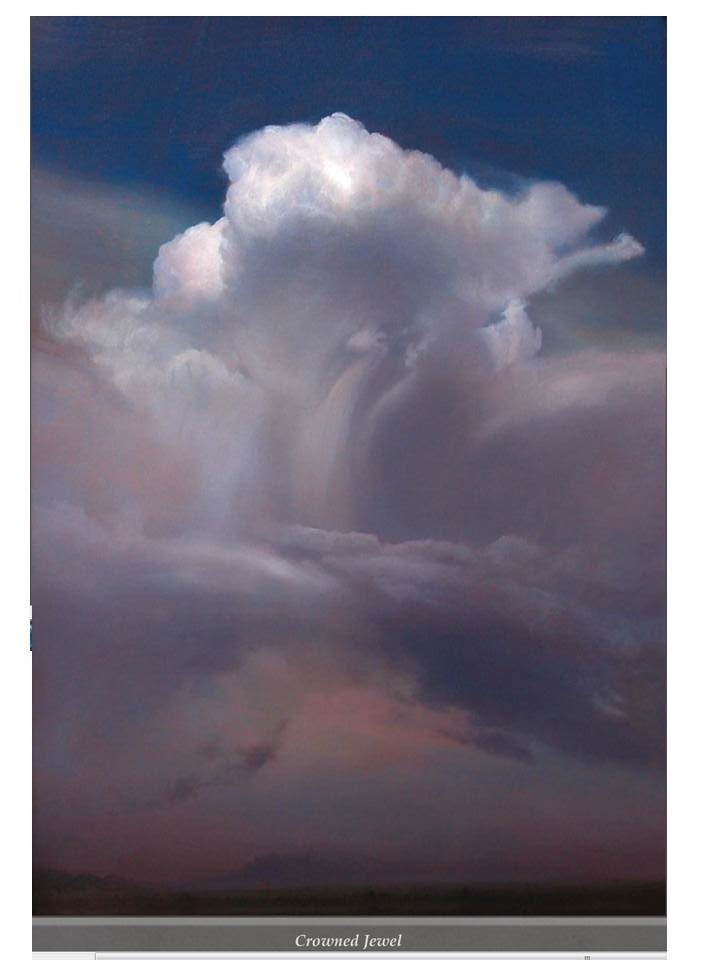

It would be easy to write Nisbet off as a throwback, and his process, style, and subject matter are definitely reminiscent of Moran, Church, and Bierstadt, but his sky paintings in particular reflect a more contemporary outlook. As in Bierstadt’s or Church’s paintings, Nisbet’s clouds seem to be animated by a sentient power, but the nature of this power and its relationship to people differs from that suggested by the Romantics.

In comparing Nisbet’s work with Friedrich’s archetypal Romantic painting The Monk by the Sea, Paul Bray writes: “With Friedrich [the weather] is turbulent and chaotic, but the centerpiece is light, and that light is of a pure, almost pristine sentience. [With Nisbet] everything suggests the hidden presence of a Divine architect, and yet the painting offers no balm, no succor: there is spiritualism but that spiritualism is almost a cold and impersonal one. Where Friedrich’s painting is organized around the encounter of man and nature, Nisbet’s painting focuses on nature in and for itself; there is no human figure; Friedrich’s monk has been displaced and we now see through his eyes. Where Friedrich’s painting suggests a supernatural turbulence which human consciousness may, by some sheer effort of will, come eventually to understand, Nisbet’s painting offers us an enigmatic and ambiguous silence.”

In Colossus and Crowned Jewel Nisbet’s central cloud formations are framed in a vertical portrait format and hover high above the viewer. The softer clouds on the periphery seem to be gathering in preparation for some powerful action. In previous decades these images would immediately bring to mind photos of atomic bomb tests but in the current age of climate change, extreme weather, and natural disasters, Nisbet’s paintings suggest Nature preparing to strike back. There is a generally Romantic ambiance to this work, but as with Wilson and Telfair the drama and awe seem to spring from a secular and scientifically informed worldview: The sky is not a metaphor for good versus evil but a dramatized evocation of the conflict between the human propensity for environmental destruction versus the regenerative powers of Nature. The symmetry and formal presentation of these cloud forms stop short of personification or deification and suggest instead a kind of secular or neo-pagan iconography of nature worship.

Wilson, Telfair, and Nisbet all find inspiration in the beauty of the sky and all capitalize on the fact that the sky lacks definite features and can take on an array of appearances. For these reasons their works, like many other contemporary sky painters, are open to a wide range of interpretations and reactions.

Even more variable in appearance than the sky, water may be the most mutable of all subjects and the second installment of this series in a future issue of Aeqai will focus on contemporary waterscapes.

- A Long Time Alone, Jane Wilson, 2004

- Looking up, Jane Wilson, 2011

- Muggy Blue of August, Jane Wilson, 2011

- Reluctant Moon, Jane Wilson

- Reduction Occurs in Less Obvious Ways, Tula Telfair, 2001

- Most Approaches Suffer from the Predictable Isolation of Schools, Tula Telfair

- Exploring New Codes, Tula Telfair

- Airship, P. A. Nisbet

- Crowned Jewel, P. A. Nisbet

- Colossus, P. A. Nisbet

October 13th, 2013at 8:06 am(#)

Beautiful paintings, intriguing analysis. Looking forward to the next installment of this series on landscapes.